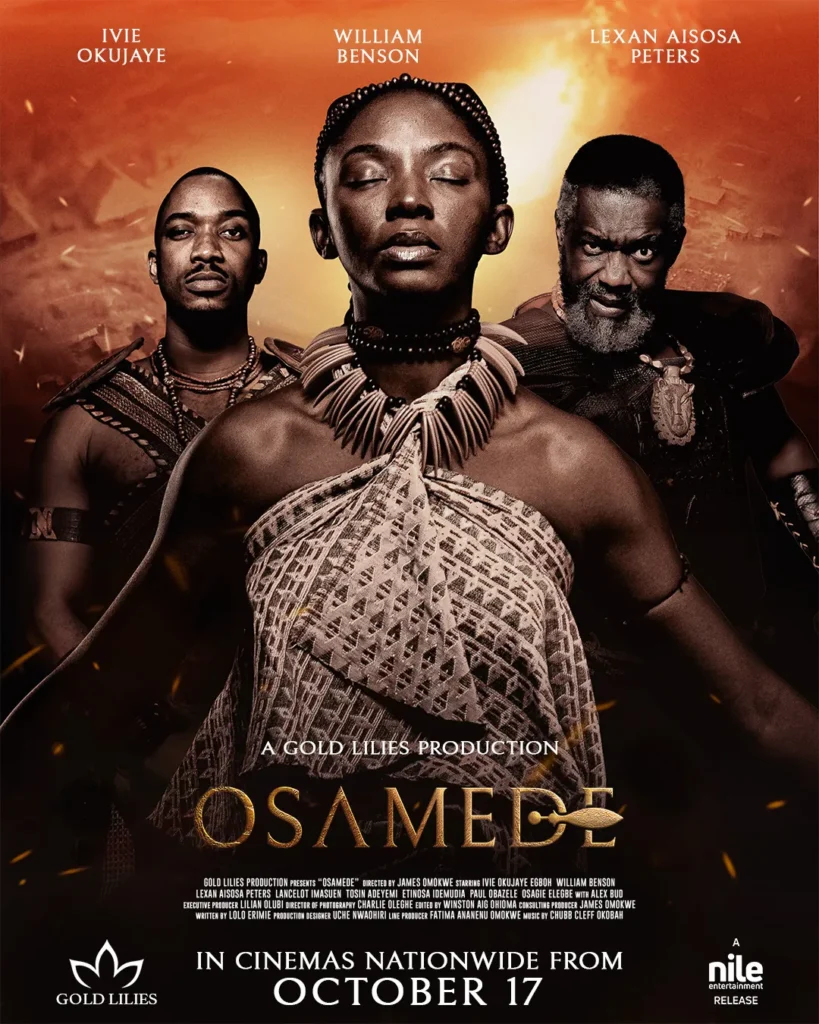

If you squint hard enough, you can almost glimpse the film that Osamede is trying to be: a sweeping historical epic with gods and magic, but also a character drama that probes the motivations and inner conflicts of its titular heroine. Even the marketing hints at this ambition; a headline on the official website reads, “Before Wakanda, there was Benin.” But where T’Challa’s journey rewards the audience for investing in the relationships of the hero and the politics of Wakanda, Osamede struggles to earn the audience’s attention. The production takes a big swing, perhaps even for the fences, but completely misses the ball.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

In February 1897, the British carried out their so-called punitive expedition of Benin. They deposed the Oba and, after carting away thousands of artworks, burned the city to the ground. This is where our story begins, amidst the high tensions of the invasion. Iyase, the King’s General (William Benson), believes he can turn the tide with the power of the Aruosa stone, an ancient relic from Osanobua, the Supreme Deity. The stone is in the custody of priests sworn to protect it with their lives. Iyase comes calling, but his intentions are far from noble. He wants the British gone, but his ultimate goal is to claim the throne. The priests refuse to surrender the stone. Using forbidden magic, Adaze (Tosin Adeyemi) hides the power of the stone in her child, the baby Osamede.

Two decades have passed. The British now rule Benin, forcing the citizens to work in the mines. Osamede (Ivie Okujaye), raised by a blacksmith (Paul Obazele), has grown up restless. She detests the British occupation and voices her anger at every opportunity. One day, an ambush by soldiers awakens something terrifying within her. Fleeing to the mountains, she begins to uncover her identity and sets out to restore Benin’s dignity.

The story originated as an idea from executive producer Lilian Olubi in 2019, later evolving into a stage production written by Paul Ugbede and Tosin Otudeko. The play debuted in 2021 and ran across twelve showings into 2022. About the decision to turn it into a film, Olubi said: “With the film, we could capture the larger narrative of the British invasion of Benin and ongoing issues of cultural restitution.” This intention is laudable but the film fails to capture the British invasion of Benin to any compelling degree. Much like Invasion 1897, directed by Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen (who appears as Aigbangbe here), the film seeks to explore a pivotal moment in the history of a people and a country, yet fails to convey the subject on the scale it demands.

The boldest choice director James Omokwe makes is to keep the film in Bini rather than relay the story entirely in English. This choice mostly pays off. Within the story, it underscores the divide between the British and the Bini, and how two decades of oppression have only widened this gulf. The two people are never truly on the same page, and it is clear that eventually, something must give and shake up the status quo. It’s also an important moment for the industry: more epics from more ethnic groups can and should be told in their native tongues on the big screen.

The story (adapted for the screen by Lolo Eremie), already tested on stage, does not meander as many Nollywood outings do. Instead, it rightly places Osamede in situations that reveal her motivations. Whether it’s a case of domestic violence, a friend being flogged senseless, or people headed for slavery, Osamede jumps into the fray, ready to help, sometimes with little thought to her own fate or survival; she does these long before she is aware of her deadly power.

William Benson’s Iyase functions effectively as a foil: his ambition and thirst for power sharply contrast Osamede’s selflessness, and his role in her mother’s death gives the conflict personal stakes. A strong moment comes when Osamede tells her Adaze, “I’m not special. I only fight for others,” to which her mother replies, “It is a special thing to fight for others.” The film explores this as a matter of destiny versus choice. When Osamede expresses no desire to accept her identity as the chosen one, Aigbangbe asks, “Who are you to change what the gods have said?” Osamede does good, not because she is attempting to fulfil her destiny, but because it’s the only way to live. She fights for others because that is who she is.

Ivie Okujaye Egboh grounds Osamede with a believable performance, a feat for the actress who is making her return to a widely-marketed major leading role on the big screen after a long hiatus—and recently seen in the lesser-known Kanaani (our 2023 film of the year which was quietly in cinemas).

However, one notices that several scenes of Osamede retain a theatrical cadence that would be more at home on stage. The film’s central flaw is that it rarely justifies why this story needed to move from stage to screen.

Adapting a play for film requires embracing cinematic tools, such as editing, framing, camera movement and sound, to the fullest, not clinging to what worked on stage. When translating a book into another language, a one-to-one conversion rarely yields the best result. The film, for all its effort, never truly entertains or inspires because it fails to use this new medium to its advantage. The cinematography rarely captivates through composition or movement. Very few moments of blocking or staging stand out, making the visual style as by-the-numbers as they come. There is one scene when the camera cranes down smoothly as Nosa (Lexan Peters) and the British officer, Frederick Wild, are having a conversation with the miners in the background, but it’s a flash in the pan.

Comparing this film to Black Panther would be unfair. Nollywood, on its best day, cannot yet compete with the legacy and resources of the Disney machine; the keyword being ‘yet’. However, Osamede invites that comparison and then fails to live up to its own promise. Working within a modest budget, the production needed a clear visual strategy to compensate. It could have embraced minimalism, evoking the sparse, eerie dreamscapes of Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, or leaned into a transcendental style in the vein of Carl Theodore Dreyer, and it could have done this without losing its identity; certain scenes needed more oomph and that strength might have come from borrowing surreal or contemplative language to express themes and emotions more effectively.

A scarcity of grand sets and costumes should not have hampered its success so greatly. The film ends up feeling small by accident, when it could have been minimalist on purpose, paying lip service to epic grandeur without earning it.

So, if grandeur is not possible, then what about verisimilitude? The costumes are too dull to transport the viewer to 18th-century Benin. Having seen stills from the stage play and marveled at its vibrant colour palette, I suspect I’d have enjoyed that production far more. Osamede, the film, almost feels like the play’s opposite in aesthetics. The entire production suffers from a lack of believability. The British soldiers stumble through their lines, often barely managing a coherent sentence in an English accent. The extras are clearly extras and move with visible self-consciousness, ruining any suspension of disbelief. Yet again, the budget isn’t the real issue; this portrait of the Benin Kingdom simply doesn’t feel lived-in.

Osamede is important for its ambition: it insists on telling a Bini story in Bini and places a woman at its centre. But this ambition needed a clearer cinematic strategy. Ultimately, the film lacks the boldness and emotional resonance to deliver the epic it promises.

It shoots for the stars but never quite achieves liftoff.

Osamede premiered in cinemas October 17.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Side Musings

- I didn’t know where else to put this. A notably poor decision is the use of low-quality AI-generated images during Aigbangbe’s narration; they feel out of place and undercut the film’s aesthetic. Stylized 2D animation would have been better. The AI images just looked like muck. I almost couldn’t believe my eyes.

- Lexan Aisosa Peters tries but never convinces as Nosa and the audience isn’t sold on his connection to Osamede.

- Hearing the Bini language on screen felt powerful. I only wish every other aspect of the film matched the boldness of that choice.

- People will argue that the AI was the right choice. Or inevitable. Or necessary because of a low budget. Or a different kind of creative outlet. Or perfect in small doses. No. That’s my response. Just, no.

- See number one again.