Click on the link to find the previous entries in our In Conversation Series.

Damilola Orimogunje wants his stories to transcend geographical locations, and he won’t let political correctness dictate his craft.

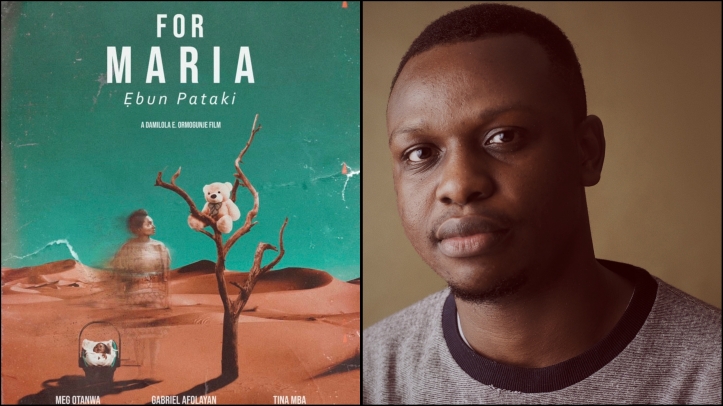

Damilola Orimogunje has been around for quite some time. In 2017, he released his short film, MO, which before its release, had won the Best Nollywood Short Film at Real Time Film Festival that same year. In 2018, he directed Losing My Religion, another short film. It was based on the short story of the same name by Nike Campbell-Fatoki. Afterwards, Dami took a hiatus and returned with another short film, Heaven Baby, in 2020. In the same year, he released For Maria Ebun Pataki, his first feature film. Both 2020 films were screened at the 2021 NollywoodWeek Film Festival, which took place virtually. For Maria Ebun Pataki premiered at Film Africa in November 2020 and it won The Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature. It has been screened in several countries around the world. Additionally, it got six nominations at the AMAA awards, including Best Writing and Directing. But this is short term. Damilola Orimogunje has been around much longer.

Related:

He is a steadfast student of the art who places the craft over racking up numbers. In his own words, “I personally won’t make a film because I’m trying to be politically correct, or for the sake of acquiring numbers without strong belief in what the subject matter is. Art is personal, subjective and nobody really puts a gun to your head to make certain films.” He further discusses the ethics of criticism, the ethics of truthful filmmaking, and the importance of books to the young artist.

A graduate of Mass Communication from Caleb University, Lagos, Dami Orimogunje, upon graduation, worked with production outlets like Lagos Television, Royal Roots, MNET Africa and FilmOne. In these outfits, Dami worked and honed his skills as writer and content producer. In 2014, he got on the creative map properly when he won the Homevida Short Script Competition. A competition sponsored by the United Nations. With short films that have been selected and screened in over 40 film festivals, Damilola Orimogunje has obviously paid his dues. He is inspired by Wong Kar-Wai (In the Mood for Love), whose 2000 romantic drama he hails as “one of the most beautiful films ever made”, citing the film’s framing, music and minimalism. His success as a filmmaker, it appears, has merely begun. He has now been recognized by reputable film, culture and art publications, including The Guardian, BBC, The British Blacklist, Sight & Sound, amongst others. In July, Damilola Orimogunje sat with WKMUp and discussed film, art, books, his influences and his ongoing film project, The Stone Drew Ripples.

This conversation took place over skype on Wednesday, 7th of July, 2021 and has been edited for length and clarity.

“I tend to think that I am drawn to societal stories that mirror societal ills. My work has encompassed issues like prostitution, human trafficking, religion fanactism, and familicide. These are prominent topics in Nigerian societies, some are talked about frequently, some are not.”

It’s nice to finally have this opportunity. I saw your film, For Maria Ebun Pataki, at NollywoodWeek and I think it was excellent.

Thank you very much, I appreciate it.

So, you are shooting a new film presently, The Stone Drew Ripples.

Yes.

We were supposed to have this interview when you were in Ibadan but we couldn’t.

Right.

You are outside Ibadan now. So, does that mean production is done with?

Uh, not exactly. Pretty much we had our principal photography in Ibadan but we still have some shooting to do in a few weeks’ time in Lagos. But the film is like 90 percent ready now production-wise.

I learnt that Meg Otanwa is starring in the movie as well.

Yes, she is.

She played a role in For Maria, is this going to be a recurring artistic partnership and also, walk me through your casting process.

(Laughs) We will find out in future if it’s gonna be recurring or not. My casting process is pretty much after writing the script. Sometimes I cast through auditions, and sometimes I just think “this person fits into this role”. For example, it was a “this actor fits the role” in For Maria but she actually read for the part in the new film.

For Maria is family-oriented and it’s about postpartum depression. It’s rarely talked about, and although sickle cell (which is the subject of his next film) is more prominent, it’s also—I don’t want to say an alien medical condition—but it’s a medical phenomenon. Is this a trend? Would you say that you are drawn to this type of stories?

I tend to think that I am drawn to societal stories that mirror societal ills. My work has encompassed issues like prostitution, human trafficking, religion fanactism, and familicide. These are prominent topics in Nigerian societies, some are talked about frequently, some are not. It wasn’t like I intended to make another health-related film. I got the script for TSDR (The Stone Drew Ripples) and I liked what the story was telling. It could connect with me and I liked the fact that it could connect with people.

“Well, I won’t agree with you that the state of arthouse film is abysmal in Nigeria because if you look at the Nigerian (film) industry five years ago, you would pretty much not be able to name many arthouse films. But fast forward to now, we have a couple of films and filmmakers moving the conventions.”

You talked about the inspiration for For Maria in a previous interview and you mentioned a French film. You said you watched it seven times and it inspired you, so I was wondering about your film background, and the films that have inspired you.

I would say, it’s evolved at different stages. I grew up watching—like everybody else—action films. The way you watch Terminator, Above the Law, Blade, Asian martial arts films.

Yeah.

If they are not fighting in the next five minutes I am not watching. But at a point when I was about to start my career I started getting drawn towards foreign cinema, a lot of artistic films. I think they just shaped my ideology about film, about how I want to approach my own filmmaking style. I still watch contemporary blockbuster films, but I am more drawn into simple indie films, the ones with authentic stories, acting.

You mentioned arthouse film somewhere there. The state of arthouse film in Nigeria is abysmal, we can’t lie to ourselves.

Okay.

I would like to know what you think about the state of arthouse films presently and if you have any proposition to make things easier for indie filmmakers.

Well, I won’t agree with you that the state of arthouse film is abysmal in Nigeria because if you look at the Nigerian (film) industry five years ago, you would pretty much not be able to name many arthouse films. But fast forward to now, we have a couple of films and filmmakers moving the conventions. It’s expensive to make a film, talk less of a film that will compete at international level. Yet, we still have folks trying to make these films without actual financial support. About proposition, folks just need to be honest while making films, be less pretentious and with consistency we are getting there. Nigerian cinema will perform exploits.

I know it’s difficult but is there a particular film you can zero it down to—whenever writers want to write a new novel, they go back to a certain book. They say this book, when I read this book, it brought sense back into my head. (Dami Laughs) Is there a film like that for you?

Yeah.

Which film is it?

Ah, so it’s actually very difficult to be able to place your hand on one particular film or filmmaker. But a film I’ll say that inspired me in some way is In the Mood for Love by Wong Kar-wai.

That’s an excellent film. (Both laugh)

It is. It’s like one of the most beautiful films ever made, and I’ll tell you why it shaped me in some way because this is me seeing someone telling a story in a minimalistic way. The film itself is gorgeous and beautiful. Every frame is a painting. The music is awesome. I’ve always been someone that really doesn’t talk much in reality. So in film, I don’t like my characters actually speaking so much as well, so watching that film was like I could make a film, have it be very beautiful, audacious, and still minimalistic and it just has all those components.

“Most times, the stories I tell are probably inspired by having a conversation with friends, or someone random that I’ll never even see again. When I’m walking on the road or sitting in public and I see someone and then in my head I’m thinking, ‘Oh this person could be like a lovely or badass movie character’, I would study such people.”

Is there any Nigerian director—from old, of course—that you think really touched you, did something to your sensibility?

Tunde Kelani. I’m Yoruba, I grew up watching a lot of his films like Saworoide, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile. Those are films that you watch and then you see your culture and yourself. We watched some at the National Theatre, and some as home video. So I think his films were one of the proponents that made me want to become a filmmaker.

Where do you live presently and how has it affected your stories? I can say Nigeria, first of all, on a broad scale, how has Nigeria affected the stories you tell? And also, where you live specifically, is there a tincture to that place that you feel has motivated you to the films you make?

I’ve lived in Lagos almost all my life. It’s a mad yet lovely city. It shapes the kind of person I am and stories I tell. I draw inspiration from my or others’ experiences. Most times, the stories I tell are probably inspired by having a conversation with friends, or someone random that I’ll never even see again. When I’m walking on the road or sitting in public and I see someone and then in my head I’m thinking, “Oh this person could be like a lovely or badass movie character”, I would study such people.

I would say there are perhaps about twelve stories altogether and it is from these twelve stories that we all write our stories whether Nigerian or American or whatever. So, is there anything you do to keep it fresh to have your work—like you mentioned earlier—authentic. Are there manners that you present your stories that you feel make them different?

I just feel the story or the character needs to be real and true. Sometimes, this comes with your experience with the story, and other times you have research. Sometimes, I like to talk to people that are going through this stuff. I think it’s drawing inspiration from the actual source, which I tell my actors as well. I mean, you could call it method acting or whatever. Basically, I tell them “you need to immerse yourself with people that have actually gone through this thing, because you are acting it, you can’t just base it off talent.” When people are watching, they should see themselves, not an actor, they should see a character that really represents them.

Subscribing to Netflix:

“If I was thinking about money first, I’d probably make one Chief Daddy wannabe or probably make like a Wedding Party kind of film. But the first thing that comes to my mind is just making a story that really resonates with me and I feel resonates with people generally. Don’t get me wrong, it could be WP or CD but I’ve not just thought of them for myself yet.”

In respect to the struggle of Indie films in Nigeria, how do you go about your business structure? Because in the end, it has to make some money. (Dami laughs) And a lot of that, do you depend on your audience for a lot of that? And if you do, what do you think your relationship is with them? Do you think about them when you make these films and what they want and how they would meet that story? How they would react about it. Do you often think about it? Etcetera. Because-

From the business angle, right?

Yes, yes. Yes.

Continue, you were going to say something.

I was then going to go into the artistic angle as well. That, for example, For Maria, that talks about postpartum depression. I don’t think the average Nigerian would know what that is. But you know, they’re going to just have this feeling that they’re unhappy after the baby is born. They won’t be able to articulate it; you understand?

Yes

So did you really consider all these things when making that film?

I feel like most artistic people tend to do this. So while I’m thinking of an idea to make films, often the last thing I think about—which is very bad—is money. (Laughs) If I was thinking about money first, I’d probably make one Chief Daddy wannabe or probably make like a Wedding Party kind of film (Ola laughs) But the first thing that comes to my mind is just making a story that really resonates with me and I feel resonates with people generally. Don’t get me wrong, it could be WP or CD but I’ve not just thought of them for myself yet.

Like you said, postpartum depression is a theme or a story that people don’t really talk about. It is a great joy for me to actually make such important and rarely topical subject matter and have it turn into a conversation after people watch the film. Back to the business angle: I feel like everything you have is marketable really, it just depends on how you market it. You could have a pen and some other person would think he can’t sell this pen and you will get a good marketer and he will make so much money from that pen. So you will think some arthouse films are not profitable but you will realise that it’s possible that an arthouse film that you make might be more profitable than the biggest commercial film released in Nigeria. I tell comrades that you need to realise your market isn’t just Nigerians. Someone in Brazil, Peru or China can watch your film and relate to it because it is a universal subject. The industry is so vast because of the internet nowadays. We have so many platforms that can globally distribute your film, and then also make money at the same time. Just have a strategy. A social impact strategy and a business strategy. It’s just really thinking deep and then not limiting your audience to just Nigerian people. I’m thankful that I have new people like my work. Some haven’t even seen my actual work. It’s just “oh I like what you are doing, I like the feel, I like the voice, I like the picture quality.” And then you immediately have someone that wants to cheer you up when you have a new project. That’s success to me.

Now I think that it’s obvious that you feel you have a social responsibility to tell certain stories and it’s becoming so political now, the film world. Are there stories that you’d shy from naturally? And how do you think we move from this political war that we have found ourselves in now. By political war now, I mean—I don’t want to be too explicit here.

No, be explicit. (Laughs)

I mean, gender politics, over-politicizing of gender politics. The constant conservative versus liberal war; ideological war online now. So how do you meander your artistic expressions in this type of political clime?

It is about perspective and what you really want to say as a filmmaker. I personally won’t make a film because I’m trying to be politically correct, or for the sake of acquiring numbers without strong belief in what the subject matter is. Art is personal, subjective and nobody really puts a gun to your head to make certain films. However, I think in reality, it’s easy to weed out the pretentious from truthful works.

Open letter to Nollywood:

As you know, we’re a film blog, we mostly write criticisms. So I’m obligated to ask you about your take on criticism in Nollywood.

(Laughs) I think I heard of a story. I don’t know how true it is. A story about someone that sent boys to go meet a critic, and beat the person up in their house. (Laughs) I mean, I heard that gist and I was like “What? What’s going on?” I’ve heard different things. For me, I just look for objective criticism. I’m firstly the biggest critic of my own work. You can’t grow as an industry if you don’t take criticism, like actual criticism seriously, and it doesn’t have to favour you. Similarly, if you don’t understand what being a critic is, don’t delve into it because you have a lot of time on your hands or because you just feel like, “Omo! I don’t like this filmmaker.” Some people are critiquing something and then you can see the choice of language is just baseless, and empty and I’m like, “What are you saying about a film if you don’t understand what film is?”

“The reason I tell people to read is because it exposes you. And it gives you room to know more about how people think. The philosophy of life and all within can actually shape your storytelling skills and, of course, it makes you quite intelligent.”

So, any advice for young filmmakers?

Read. Watch films. Collaborate with like minds. Be open to conversations with people. Festivals will reject your film, people would say you’re not good enough, just keep going, learning, keep making. Yeah, and that’s…that’s the script.

On a parting note, final parting note, ‘jale jale’, (Dami laughs) what is the name of your favourite book?

Oh gosh. I don’t like this question (Ola laughs) I will say probably the last book I read. And the last book I read which is still stuck in my head is, “No Longer at Ease” by Chinua Achebe.

Achebe.

Yeah. I think it’s a brilliant, excellent book. I am currently reading something else but I haven’t gotten in-depth.

What book are you reading presently?

I’m reading Ben Okri’s The Famished Road.

That’s a brilliant book.

It is a brilliant book. Ben Okri is really intelligent, which is something else I actually look out for. The reason I tell people to read is because it exposes you. And it gives you room to know more about how people think. The philosophy of life and all within can actually shape your storytelling skills and, of course, it makes you quite intelligent.

A suggestion on Ben Okri. When you are done with The Famished Road, read Starbook. The real magic happens in Starbook.

Oh really? I haven’t read it. I will probably check it out.

You will have a good time reading that too. This was excellent. I really enjoyed speaking with you.

Same here.

I hope we meet physically at a later date.

No wahala.

I look forward to The Maria, For Maria, seeing it again at a later date. Thank you very much for your time and patience.

If readers feel some questions have been left unanswered, you can follow the director on twitter where he drops filmmaking tips and raves about football, and on Instagram for photo teasers from his future projects.

You can rent Losing My Religion on Amazon Prime Video.

Click on the link to find the previous entries in our In Conversation Series.

Subscribe to our mail notifications here:

5 Comments