There was a time when going to the movies in Nigeria meant calling friends, buying tickets, and heading to the cinema for a big release. During the week, students and NYSC members could walk into the nearest Silverbird or Filmhouse to catch a film at a discount price that didn’t break the bank; a shared escape after lectures or a workday. The popcorn smell, the hum of excitement, the hush before the screen lit up. Cinemas were more than screens; they were meeting points for a generation.

Today, things look very different. Instead of forming lines at ticket counters, many Nigerians now press play from their phones, almost like a home video experience. Netflix, Prime Video, and Showmax have seemingly become a clear option ahead of the box office. Many more also turn to less official online sources, where the latest films circulate freely and illegally. Nollywood now stands between two realities: the enduring magic of the big screen and the unstoppable pull of the digital world.

This isn’t just a lifestyle shift. It’s a cultural and economic turning point, one that will decide how Nigerian stories are distributed, who profits, and how audiences connect.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp).

The Rise and Struggle of Nigerian Cinemas

Modern Nigerian cinema culture truly found its footing in the early 2000s, after years dominated by straight-to-DVD releases. Silverbird Cinemas’ arrival in Victoria Island reignited a dormant tradition, and soon, others followed; Genesis Deluxe, Filmhouse, Ozone. But the real spark that revived belief in cinema storytelling came in 2009 with Kunle Afolayan’s The Figurine.

The Figurine wasn’t just a well-made movie; it was proof that Nollywood could shine again on the big screen. It inspired a wave of filmmakers to think bigger; visually, technically, and thematically. The success of later blockbusters like The Wedding Party (2016) and Omo Ghetto: The Saga (2020) confirmed that Nigerians were ready to come back to theatres.

But that momentum soon hit rough terrain. Ticket prices crept up, from 3,500 naira to 5,000 naira in major cities, while economic pressures deepened. Cinemas remain clustered in urban areas, leaving much of the country out. For many who could previously go, movie-going became an occasional outing, not a weekly pastime.

Then the pandemic arrived. Cinemas shut their doors, and habits shifted. Audiences were more satisfied to get the same films and many more from home. When theatres reopened, the crowd never fully returned.

The Streaming Boom

While cinemas struggled, streaming quietly took center stage. Netflix officially launched and started taking Nigerian films to a global audience, trending in multiple countries. Lionheart and Oloture, for example, proved that Nigerian stories could travel far beyond home and that the internet was the new distribution network.

Next came Kemi Adetiba’s King of Boys: The Return of the King, which opted for a streaming release over cinema (as was originally expected for the sequel). The move surprised many, but it paid off financially, and it became one of Nigeria’s most talked-about releases that year. Slowly, filmmakers’ attention was turning to streaming as a viable first option.

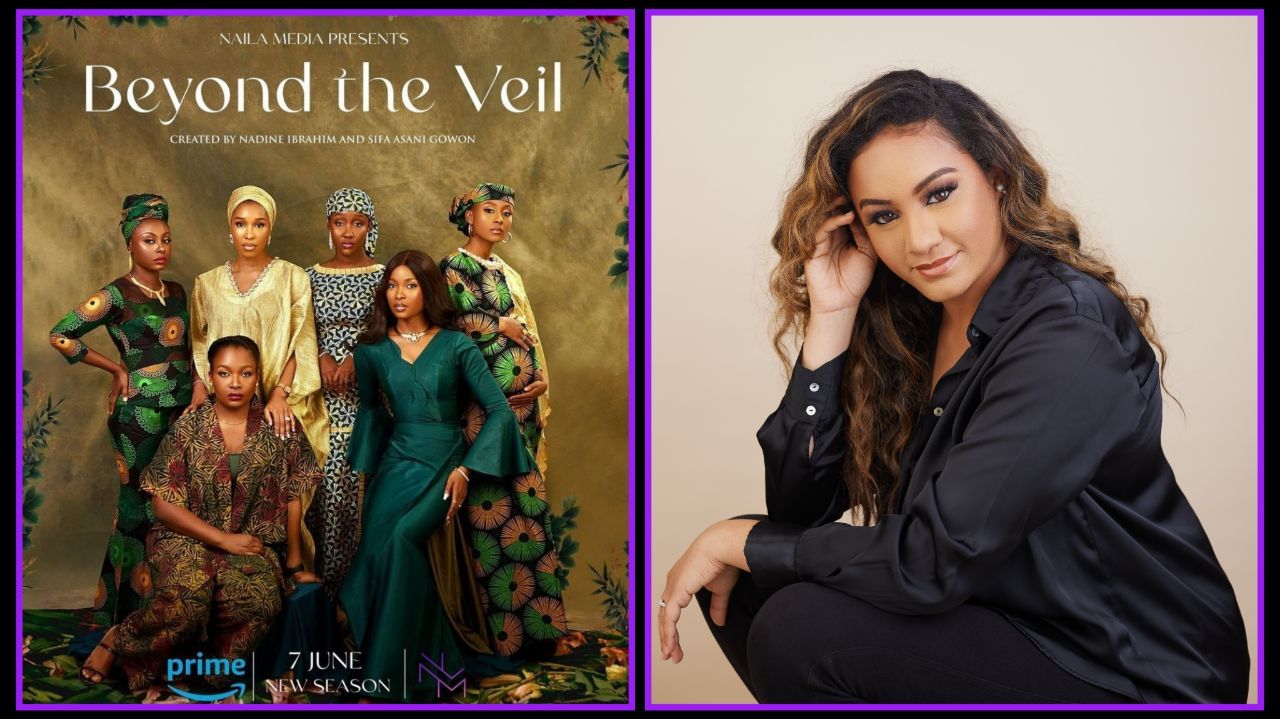

Then Amazon Prime Video entered the market in 2022, exclusively signing filmmakers like Jade Osiberu and companies like Nemsia. Osiberu’s Gangs of Lagos premiered as a Prime Video original in 2023, sparking a major debate within the industry about the future of theatrical releases. Some cinema owners voiced concern, while others saw the shift as inevitable.

Meanwhile, Showmax continued expanding with African originals, building loyalty through local content and popular reality shows like Big Brother Naija and the Real Housewives franchise. Although streaming made films more accessible, piracy remains a major concern; illegal uploads on Telegram and rogue sites still eat into filmmakers’ earnings.

Yet, for audiences, streaming is freedom. A student in Kano or a nurse in Enugu can now watch the same new film as someone in Lekki, instantly, legally, and affordably. Streaming flattened geography, turned phones into theatres, and opened Nollywood to the world.

Filmmakers in the Middle

For filmmakers, both worlds come with trade-offs. Cinemas bring prestige: red carpets, real-time audience reactions, and that unique sense of occasion. But distribution is limited, and profits depend heavily on turnout.

Streaming, on the other hand, offers reach and security. Licensing deals mean guaranteed payment, and the global audience means visibility far beyond Nigeria’s borders. Jade Osiberu’s move from Sugar Rush (a major cinema success) to Gangs of Lagos on Prime Video reflects this shift. Kemi Adetiba’s Netflix-exclusive King of Boys sequel also expanded her global recognition and introduced her work to new audiences worldwide.

In short, cinemas deliver physical energy, but streaming, at the time, delivered stability and more filmmakers were learning to balance both as post-theatrical licensing increased. Quite a number of cinema titles found their way to Netflix and Prime Video (which signed deals with Inkblot and Anthill) after their cinema run. Films like Brotherhood premiered in cinemas before heading to streaming, giving each format its moment. It’s a practical compromise, and a sustainable one for the filmmakers.

With these post-theatrical deals, cinema trips became even less necessary for audiences, becoming occasional, reserved for holidays, dates, or blockbusters. Meanwhile, streaming fits perfectly into daily life. ₦1,200 for a monthly Netflix mobile plan beats a single ₦4,000 ticket. With data getting cheaper and smartphones everywhere, digital viewing is simply more practical.

But that doesn’t mean cinemas are obsolete. They just serve a different purpose now; less every day, more event-based as seen with star-led films across the year and the December release window.

Nonetheless, cinemas still offer what no home setup can replicate: the big screen, surround sound, and the collective thrill of shared laughter or suspense. Streaming, however, owns convenience and accessibility. Together, they can serve different moods, different audiences, and different pockets.

Nollywood’s Next Chapter

So, where is Nollywood truly heading after the slowdown of foreign streaming investment and the embrace of YouTube and the launch of a number of Nigerian-based streaming platforms? Is it towards that locally-led streaming future, but not one that leaves cinemas behind?

Moses Babatope, Group Executive Director at Nile Entertainment, put it best in an interview with Banke Fashakin of Nollywire:

“I think that the prosperity of Nollywood, as much as I love cinema; and I do think cinema has a role to play and will continue to grow – the real prosperity of the industry lies on digital platforms. And I believe a local player is going to win that race. I pray that the local platforms don’t let me down. I hope this becomes a challenge to them; that we get off our high horse, stop trying to compete in silos, and come together to form a proper, Avenger-like platform that caters to the realities of our market. That’s where the true prosperity comes.

Cinemas cannot show every film; that’s the truth. There needs to be a certain level and quality of films that make it to the big screen. But the barrier to entry for digital is much lower – and YouTube has already proven that. What we’re now looking for is how creators can get paid more to make more audacious, more entertaining, and more audience-specific content that they continue to be rewarded for. And we must make those films in ways that audiences can legally and securely consume them.”

His perspective captures the heart of it: the industry’s future lies in collaboration, audience consideration and healthy competition.

Cinemas will evolve, offering premium experiences that justify the ticket price, from immersive sound and reclining seats to themed nights and the fledgling community screenings. Streaming will continue to dominate everyday viewing and international exposure. From VHS to YouTube, from box offices to streaming charts, the industry has always adapted and jumped ship to the next shiny toy. The next era will show us the results of filmmakers who learn how well to make use of all the existing channels to reach the mighty audience, knowing which to use at each point of the distribution cycle.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.