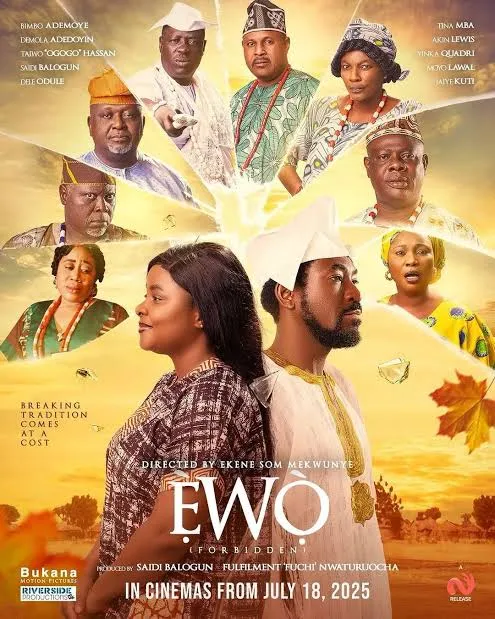

Ewo (Forbidden) opens like an ethnographic homage to the African marketplace. Directed by Ekene Som Mekwunye (One Lagos Night), it presents a colourful swirl of commerce, culture, and chatter. With wide shots of women displaying their wares, traders haggling over prices, and a narrator discussing the contrasts between African and Western marketplaces, the opening sequence could easily be mistaken for a documentary. But this visual facade quickly gives way to a narrative of love. Or so it seems.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

Beneath this joyous exterior lies a tense narrative about the cost of defying tradition in a sensitive society where religion and culture struggle for dominion. The premise is undeniably compelling, but its impact is undermined by shoddy writing and direction, plus inconsistent performances, which deprive the film of its emotional and thematic reasoning.

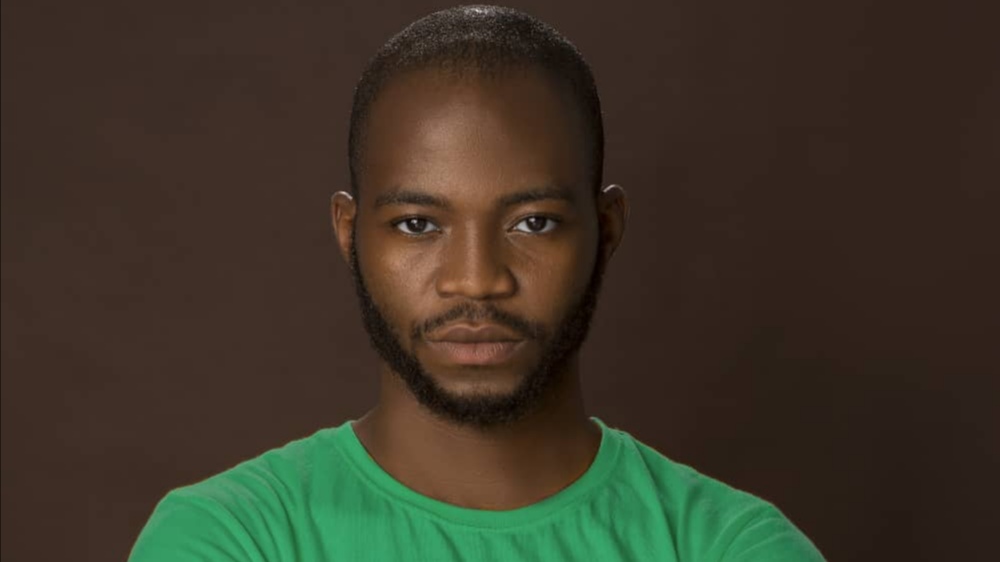

The story begins in the marketplace, where a sweet-tongued Kunle (Ademola Adedoyin) meets a vivacious Àdùnní (Bimbo Ademoye). Their chemistry is instant. And for a moment, the film pretends to be a love story. But its subject of love is merely a conduit, an illusion that masks a deeper, darker necessity. It’s mainly about death and the forbidden, ties to customs and religious fanaticism.

And Kunle is the illusion marked with a darker responsibility to tradition. Unbeknownst to Àdùnní (and us), he carries a destiny entangled with the kingdom’s future, a secret that transforms the supposed love story into something more tragic and ceremonial.

Ewo explores a moment of existential, religious, and cultural crisis tied to the death of Ológbojò, the king of the fictional Ogbojò community. The king (Kunle Coker) dies after a prolonged sickness. His youngest wife, Ewatomi (Moyo Lawal), a newly converted Christian, absconds with his body to avoid the traditional ritual needed for his burial and enthronement of a new king.

At first, the film’s focus on the love affair between Kunle and Adunni isn’t well-defined. After a few unconvincing scenes about the love story and the disappearance of the king’s corpse, the actions awkwardly hasten to save the earlier sloppiness of the film.

Still, the romantic subplot between Kunle and Àdùnní feels emotionally flat. Their conversations lack depth, and their chemistry never moves beyond surface-level flirtation. As a result, the love angle does little to heighten the emotional stakes or anchor Kunle’s later dilemma in pathos until it’s linked to the king’s demise and burial rite.

We later understand that Kunle, whose identity and relationship with the king were a mystery, is an Abobaku (the king’s horseman). Yoruba cosmology dictates that a king must never be buried alone; his Abobaku, the man appointed to die with him, must accompany him before sundown. But since Queen Ewatomi has fled with the king’s corpse, Kunle decides to subvert the tradition by running away. Ewatomi and Kunle’s actions throw the community into a crossroads. What follows is chaos, veiled in silence, moral panic, and a battle for spiritual balance.

Ewo’s theme is partly related to Biyi Bandele‘s Elesin Ọba: The King’s Horseman (2022). But where Elesin Ọba explores the cultural collision through the lens of colonialism and philosophical difference, Ewo looks inward, reflecting on the atrocities of religious fanaticism and moral rigidity.

Queen Ewatomi emerges as a fanatic whose Pentecostal convictions clash with the ancestral traditions of her kingdom, similar to Mike Bamiloye’s Mount Zion films like The Gods Are Dead (2000) and Apoti Ẹri (2009). Like the fiercely Pentecostal characters in Bamiloye’s films, Queen Ewatomi condemns customs and traditions with prophetic rage. In her mind, customs and traditions are barbaric. And she believes she’s not disrupting traditional practices but redeeming them by absconding with the King’s body. With this, she feels her action rescues her husband’s soul from “hellfire” and directs the community to Christ for salvation.

This shift toward internal religious conflict is where Ewo makes its most audacious thematic claim, asking a uniquely Nigerian question: when belief systems collide, whose truth prevails? With this question, religion, both traditional and the Abrahamic, becomes a character, pushing its ideologies with violent absolutism. For a story with such heavy and timely subjects, Ewo remains lukewarm for most of its runtime, as a result of its languid pacing and muted tension.

A community is in chaos, and the restless chiefs are locked in a constant clash of words, their disputes fueled by uncertainty and confusion. Tensions run high as they bicker, each vying for control while the chaos around them deepens. For example, the council scenes drag on with redundant arguments that fail to escalate the sense of immediacy or spiritual dread. It’s a missed chance to enhance the dramatic tension, fueled by uncertainty and confusion.

Towards the end, however, the actions are hurried but not commendable. In a lively, fast-paced manner, the palace guards run around, searching for the queen to retrieve the king’s corpse. After collecting the corpse, they learn that Abobaku has fled. A humorous scene unfolds as the guards chase Kunle in a cartoonish manner, generally ungrounded, almost out of context.

This scene, tonally inconsistent with the rest of the film, plays like misplaced slapstick, undermining the severity of Kunle’s flight and making light of what should have been a life-and-death pursuit. This face-saving attempt by the director, who also penned the story, isn’t persuasive.

From a technical standpoint, Ewo visuals are modest and captivating. The camerawork, though not exceptional, effectively serves the story. The market scenes are full of life, depicting the vibrant nature of African markets. Whereas the palace and shrine scenes are dark and claustrophobic, reflecting the characters’ confusion and spiritual entrapment. The incorporation of Yoruba percussion, chants, and incantations grounds the film in its cultural context. However, the overuse of these elements sometimes diminishes the emotional impact of key moments.

Ewo, performed in English and Yoruba, takes a more straightforward approach in its character development, resulting in somewhat conventional portrayals. Ademola Adedoyin’s performance as Kunle starts with great energy, but halfway through, slips into caricature for lack of decisive motivation. His reactions in pivotal scenes, such as his decision to flee or confront his fate, are emotionally muted, robbing the character of complexity.

Àdùnní, though energetically played by Bimbo Ademoye (Big Love), is more a symbol than a person: her desires and dreams to uplift her community are swallowed by the film’s larger metaphysical obligations. Queen Ewatomi, played with mild religious fury by Moyo Lawal, is arguably the film’s most dynamic character: she is at first a villain, later a victim, and finally, a cautionary tale. But no one in Ewo is deeply memorable, perhaps because the story itself is not driven by character but by inevitability.

Ewo (Forbidden) premiered in cinemas on July 18.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- Strangely enough, the plot of Ewo coincidentally depicts the recent controversy in Ijebu Igbo, where traditional rulers and Muslim converts clashed over burial rites and the spiritual obligations tied to the death of King Sikiru Adetona, the Awujale of Ijebu-land.

- Perhaps Ewo’s most potent message is not just that tradition is sacred, but that breaking it comes at a cost no one truly wants to pay.

- It’s hilariously absurd, almost Shakespearean farce, to watch a palace guard, who clearly doesn’t understand a word of English, fiercely reply in Yoruba to a bewildered pastor, only to then gesture at another guard, the “official English interpreter,” to step in. Apparently, in this kingdom, misunderstanding is a protocol.

- It’s interesting to see the pastor and the palace’s “official English interpreter banting about whose religion’s God is the most powerful and can save in time of trouble.