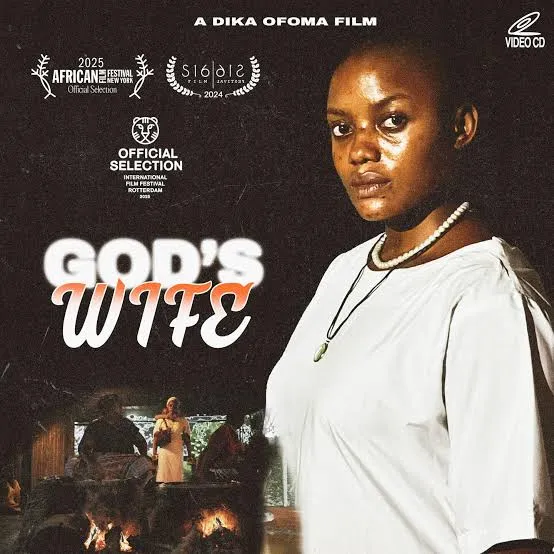

God’s Wife opens with the first of many impactful moments. A forlorn woman dressed in white while her hair is aggressively cut with a pair of scissors as two women sit on her sides casting occasional looks of disdain; the framing, in the name of the father, the son and the Holy Spirit. From this moment till the end of the film we see a widow whose dedication to her catholic faith clashes with the demands of tradition after her late husband’s brother makes sexual advances to her.

In this film, writer-director Dika Ofoma is in expert control of the rhythm of the narrative. He understands that a short film must hold its breath before moments of release and plays with silence, dialogue and the lack of it to curate a sort of cinematic reflection of a homily. The central narrative exists on a meditation on Catholicism, we hear the main character pray the rosary in Igbo as she fingers her string of beads and navigates her dilemma under the guidance of her faith. In a pivotal scene at the end of the film we see the camera pan away from the characters and land on a framed picture of baby Jesus and Mary, proving once again the foundation of Catholicism this film rests on.

Building on this is the brilliant Onyinye Odokoro, clad in white as the widow. She is rarely speaking but always praying, her face a devastating reminder of loss, as she seeks advice from an elderly woman on what to do about her brother-in-law. She complicates her grief with worry as she struggles with this betrayal of her faith. In one scene, she cries at the grave of her late husband and we are made to sit with her predicament, she resists the pit of exaggeration with her acting but mines a feeling of grief many of us know all too well.

Odokoro shares some scenes with Uzochukwu Nnadi as Akpuma, her brother-in-law. His body language expertly exudes the entitlement tradition has given him as he thunders through the house. In one scene, he comes into the house to meet his sister-in-law helping her daughter do her homework at the dining table, he hovers over them and reaches for the book in an act of pretentious fatherhood before he moves on to the real reason he came.

God’s Wife utilises all the tools of a short film to create fifteen minutes of a story that could have been fifteen years. The natural sounds fill the film and we hear no music till the closing credits, the lighting is moody but not distracting—the dining table scene mentioned earlier comes to mind, and the acting grounds you in the life of a woman who might have lost her husband but will remain married to God by any means necessary.

God’s Wife screened at the New York African Film Festival 2025, which took place May 7-13.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- There was a blackboard with instructions and rules for processing garri just behind Onyinye and the woman she came to seek advice from. I liked that detail.

- The thud of the sand on the coffin to lead into the title card was genius, it worked so well.

- I went to listen to the hymn used as the closing credits, the director has an interesting story on how he was able to clear it.

1 Comment