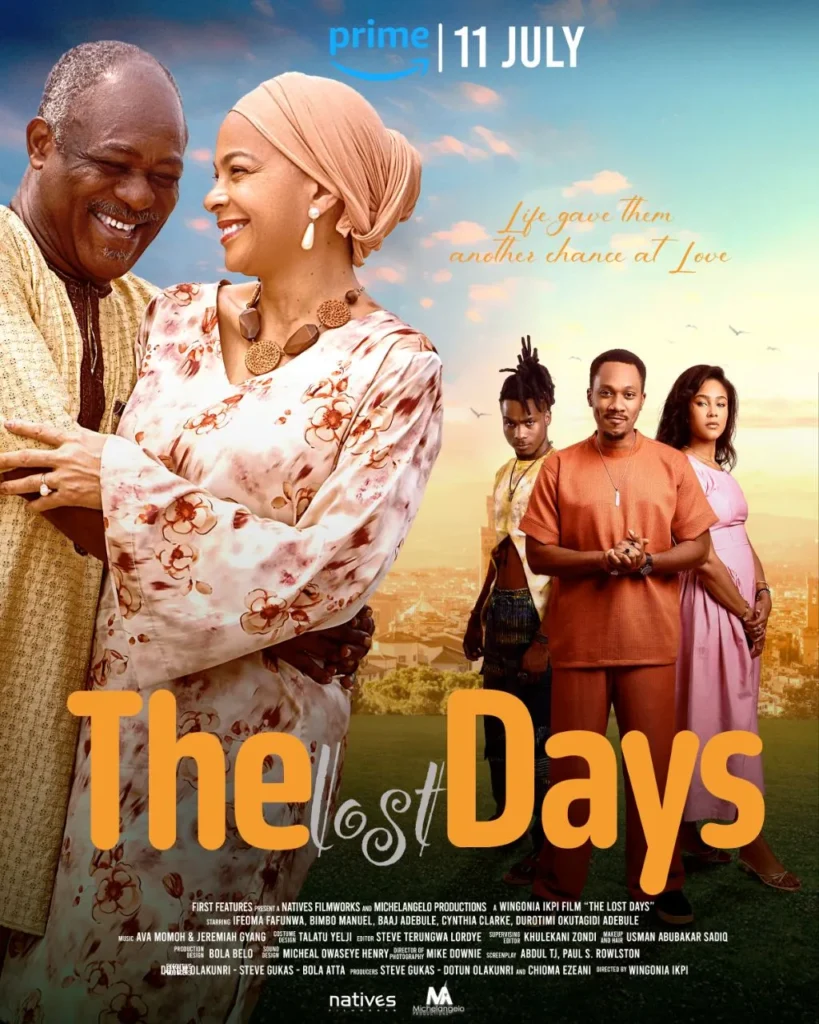

I began watching The Lost Days last Saturday inside an Uber while stuck in an infuriating traffic with a sexist driver who kept yelling curses at the female driver in front of him. The day before, I had told my editor that I didn’t feel compelled to renew my Prime Video subscription just to watch this film, but by the next morning, my mother had put up the same film on the family WhatsApp group as her best movie of the week. My elder brother dropped a weary face emoji because it’s a Nollywood film. My father asked if that old man on the film’s cover was Olu Jacobs. Again, my brother typed a double weary face emoji. He reminded me of this film critic on Twitter.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

The Lost Days, directed by Wingonia Ikpi in her debut, is First Features’ 9th production and their second this year after Katangari Goes To Town. I’ve enjoyed and written about a couple of First Features films in the past, and if anything, they often share an ambitious effort to make impressionable films. Following in this path, The Lost Days is an introspective probe on second chances and the weight of lost times though it does so with a restraint that feels both refreshing and, at times, frustratingly contrived. The film unfolds like a quiet stream, with a deliberate, almost meditative pace.

At the heart of the story is Chisom Agu, a successful business mogul portrayed by the charming big-screen newcomer Ifeoma Fafunwa (a stage veteran) who brings a quiet strength to the role. Recently declared cancer-free, Chisom is a woman at a crossroads, driven by a sudden urgency to confront a past she’s left buried for decades. Her daughter, Nkem (Cynthia Clarke), is not pleased with the news that her mother is going to their hometown, Nsukka. There is a hint of familial dispute going on over there, although the script doesn’t dwell on that; it doesn’t have to.

But the next scene is not Nsukka. You can tell by the cluster of rusty red roofs of square houses sitting close to each other and the looming mountain on the top of the lush greenery. It is Abeokuta. Nsukka usually takes on a life of itself whenever it appears in a film, but so does this Abeokuta. Perhaps because they are both ancient towns. Anyway, we wait to see why Chisom chooses to mislead her only daughter about her journey. The answer is at the compound of an elderly man, Kolawole (Bimbo Manuel), resting languidly under a tree shade. It’s obvious they know themselves from the casual way they exchanged pleasantries even though there is an awkwardness to this familiarity. They haven’t seen each other in over thirty years, but it doesn’t take long for them to start bickering and bantering as if no time has passed between them. But the movie is not confessional, and the characters don’t rush into further revelations. There is a patience at work here, even a reticence that reflects who they have become.

Bimbo Manuel’s Kolawole is a man beaten by life’s disappointments, his face etched with the kind of quiet grief that comes from mourning his own fate. His two sons are polar opposites; there is Moses, played by Baaj Adebule (The Men’s Club), who works in Lagos and Kola (Durotimi Okutagidi) who goes around the village getting into fights and filling the entire house with marijuana smoke. If Kola Jnr. feels threatened by the presence of Chisom in that house, Moses on the other hand shows her respect and kindness that you wonder if he would feel the same way about her when his father breaks the big news to him.

Fafunwa and Manuel share a tender chemistry, their performances finding nuance in small gestures—a glance held too long, a laugh that catches in the throat. There’s a scene where Chisom and Kolawole sit on a rock overlooking a lake. It is a brief but idyllic moment, a frame drenched in melancholy and preciousness, of two lovers in contemplative mourning of a time lost, of all the things that could have been. Director Ikpi films them in an uninterrupted take so that the scene feels like it exists in real time.

But these moments are short-lived as the film plunges into the infamous third act curse in Nollywood films. What begins as a subtle character study veers into a tangle of convoluted narrative choices, with haphazard shots and flat photography undermining the film’s earlier elegance. This shift in tone and pacing is jarring, especially after the film’s promising start. The quirky turn of action feels less like an organic evolution and more like a script struggling to fill its runtime. There’s a cynicism that creeps into the viewing experience here, a sense that the film is reaching for emotional profundity without fully interrogating the complexities of its themes. Regret and redemption are not simple arcs to be tied up with a bow; they are rough, lifelong processes that resist easy closure.

Still, there are more moments of undeniable beauty. Fafunwa shines in her ability to convey Chisom’s quiet resolve, her eyes carrying the weight of a life reshaped by illness and time. Manuel, a fellow veteran, matches her with a performance that feels lived-in, his Kolawole, a man who has made peace with his solitude but not his regrets. Kolawole and Chisom’s love story is not explored in this film, even as a back story. I like that this screenplay by Abdul Tijani-Ahmed (Red Circle) and Paul S. Rowlston has the discernment to avoid the complications of rekindling a romance between these two older people, instead allowing them to explore this abandoned space with each other as they reflect on their lost love and regrets. You can feel it in their eyes and in their silence saying to each other, It’s not you I mourn, it’s time. The dialogue is restrained, though not always tight, allowing silences to carry as much meaning as words. Exposition is minimal, a choice that respects the audiences’ ability to piece together the fragments of Chisom and Kolawole’s past.

For all its early grace, The Lost Days struggles to grapple strongly with its central themes of regret and redemption. The film seems to assume these ideas will resonate simply because they are universal, but its execution feels rushed, as if it’s checking boxes rather than digging into the messy truth of humanity. Regret, for instance, is presented through Chisom and Kolawole’s shared memories, but the script shies away from the raw, jagged edges of their pain. Instead, it leans on familiar tropes—reconciliations that feel too neat, resolutions that arrive too conveniently. Redemption, too, is handled with a heavy hand, particularly in the film’s final moments, where a turn of events disrupts the quiet rhythm established earlier. The Lost Days seems to want the weight of these ideas without the burden of their ambiguity, and in doing so, it sacrifices some of its earlier authenticity.

The Lost Days premiered on July 11 on Prime Video.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- This aunty just got to Abeokuta and she’s already doing friendship with the son of the man in whose house her mother got missing in the first place, even hanging out with the son by the lakeside while her mother is still missing. I don’t get it because if it’s me, I’m rounding you all in that family up as suspects.

- “…we grow so old and lose our beauty and then appreciate how nature has been able to keep hers” is my favorite line in the film.

- That scene where Chisom said she would go and arrange cold water for Moses and Kolawole and herself got me laughing because if it were Kola Jnr she said that to, that craze would have asked her swiftly in Yoruba if she was the guest or the owner of the house.

- And this brings me to a similar observation, Chisom is barely a day old in Kolawole’s house and she has arranged a portrait of her and her daughter on the dressing table. And trust Kola Jnr to do the needful when he saw it.

- I wonder how Nkem managed to get hold of 50 million naira in a day without tipping off suspicion from the bank at least.

- That Tawa girl no get sense. Now see her swollen eyes and mouth badly battered because of small bag of cash she helped to retrieve. She doesn’t even have the mouth to tell her cell mate that the crying man she is comforting from the next cell is her man.

- Kill Boro, flawed as it may be, still remains my best First Features Film, and it has the themes of regret and redemption as its central theme as well.

- My brother is co-asking if Baaj Adebule and Durotimi Okutagidi Adebule are also real life siblings because of the shared last name. Turns out he later saw the film after all, in spite of those cynical emojis earlier on.

3 Comments