Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article misstated the average distributor share of gross box office revenue; the figure has been corrected to reflect an industry average of around 5%, subject to individual deal variations.

Every filmmaker wants their film to make some money. The revenue helps make the case for the next film, and the one after that. Beyond the individual filmmaker, box office performance also signals the health of the industry to stakeholders. Even when it isn’t your film—and regardless of how successful it is—reliable, trackable box office data informs decisions. It shapes confidence. In that sense, reliable data feels almost like magic.

So what makes this difficult in Nollywood? Where does it get tricky for stakeholders?

How do we build a sustainable and expansive industry without reliable data? How do we move beyond repetitive formulas if we cannot properly judge the life cycle of films? When box office data is missing, incomplete, or unreliable, performances might hastily be labelled as failures. Those judgements rarely account for context, rollout, or audience access.

The consequences ripple outward. The larger industry suffers, both on the days a filmmaker sits comfortably under the rent-seeking tent, and on the days they find themselves a metre outside it. This problem becomes especially visible when something new enters the market: a different genre, a fresher voice, or an alternative to the season’s highly demanded film. Without dependable data, these films are the first to be misjudged and prematurely written off. The bar on the opening weekend (and subsequent weeks) is set so high. And we all just have to accept it.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

This has now happened a few times this year (at least from what we’ve been able to observe) largely because of the high-profile nature of the affected films. Red Circle earlier in the year. More recently, reports of similar treatment with Toyin Abraham’s Oversabi Aunty and Niyi Akinmolayan‘s Colours of Fire. And it likely happens far more often than we ever hear about.

While audience demand undeniably plays a role in exhibition treatment, Nollywood’s first-weekend trap is a reminder that films deserve a fairer shot at the big screen. There is no real workaround for that. Too often, these films are quickly dismissed as “not high-demand enough,” based on narrow and premature readings of performance.

But how do we build audiences without first conditioning them? How do we expand taste without stifling creativity? And how do we expect the industry to grow if new or alternative offerings are never given the room to breathe?

Red Circle, produced by Nora Awolowo’s Rixel Studios, arrived in Nigerian cinemas in June with the momentum of an intentional release: star‑led promos, brand partnerships, multiple teasers, talk‑show visits, premiere events and a fairly active audience primed to watch. But by Sunday of the opening weekend, a different kind of buzz had taken over. Some audience members posted on social media, reporting missing listings, cancellations mid‑screening, and relegation to odd time‑slots despite being newly released. And during ticket reissuing, fans were often advised to “watch something else.” Competing films included fresh titles like Iyalode, Ballerina, and older titles like Mission Impossible 8, Sinners, Ori Rebirth, Imported Wives, and My Mother is a Witch.

“This is looking like a deliberate effort to sabotage RED CIRCLE across Nigerian cinemas,” one user posted on X. This echoes a sentiment now all too familiar for filmmakers and audiences.

These are not isolated glitches. Red Circle joined a growing list of Nollywood titles undermined not merely by “poor reception”, but by a flawed exhibition model.

Take Kenneth Gyang’s AMAA-winning Confusion Na Wa, a film that screened successfully on the festival circuit. Yet when it entered Nigerian cinemas, it struggled to reach not necessarily a broad blockbuster audience, but its very own unique audience. That early incident hinted at an ironic budding deeper issue which we still see today. Festival accolades don’t guarantee domestic support, especially when distributors and exhibitors don’t actively champion the work, which everyone already understands. Ironic because an ambitious auteur-driven non-mainstream project, The Figurine, re-opened our cinema doors due to its success in 2009. So, what failed to be nurtured in the years that followed? And what, instead, was embraced too readily?

In 2017, veteran actress Shan George criticised cinema operators for functioning like “cabals.” She claimed that if filmmakers didn’t cast certain big-name stars, their films were rejected. Her frustration at that time proved what many perceived to be a gatekeeping culture that sidelined anything seen as not commercially obvious.

But as Moses Babatope, Current Executive Director at Nile Entertainment and Fmr Group Executive Director of FilmOne, explains in a 2025 interview with Banke Fashakin on Nollywire’s The Spotlight, cinemas didn’t step into distribution simply out of vanity or a desire to hoard power. They did it out of necessity. With an inconsistent supply of films that could hold the big screen, cinemas began distributing (and even producing) to “keep the lights on,” using their direct access to audiences to guide content that was more likely to sell.

In 2019, the threat to Nigerian filmmakers came from outside. They voiced concerns over Hollywood dominance in local cinemas, regardless of how Nigerian films performed at the box office. Exhibitors replied that it was audience-driven. Once again, it was business and, understandably, still is business.

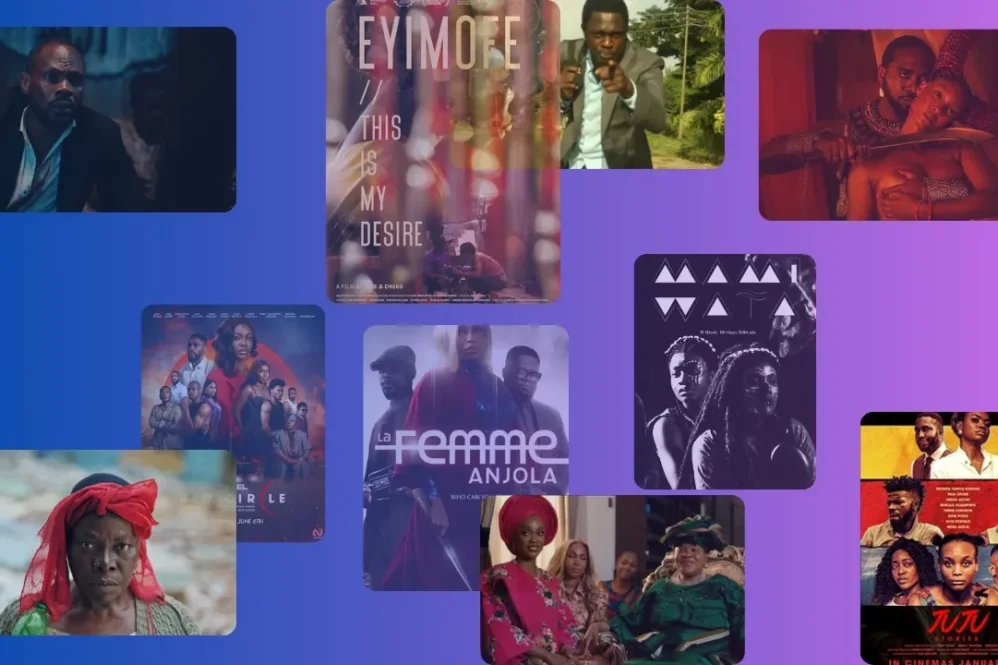

Recall Eyimofe (2021), an auteur–driven gem given weekday morning screenings that killed its reach. It becomes clear that the current system preserves cinema success for pre-packaged “sure-bankers”, celebrity-driven films. This is in a way that cultural commentators have tied Funke Akindele’s box office success to her strong social and financial capital (built around a widely beloved brand) rather than a heavy reliance on a wonder-making distributor support, which many other films depend on far more extensively but usually missing.

By contrast, filmmakers without comparable brand power have often found themselves at the mercy of exhibitors. Mildred Okwo’s unfortunate treatment at the box office also speaks. Surulere (2016) was yanked in its second week despite strong openings (“#2 overall”), sparking her public critique of unfair exhibitor tactics. And La Femme Anjola (2021) was pulled from most Filmhouse cinemas to make way for their in‑house Prophetess (an Akinmolayan-directed project), even after ranking second at the box office.

Moses Babatope acknowledges that such tensions exist, likening them to protectionism in international trade. Not always malicious, he argues, but often about protecting one’s own investment and “giving it the best chance.” He warns that it could be dangerous for the sector if abused, but insists that genuinely competitive films with strong demand still stand a chance: “The audience will decide very quickly if a film is desired.”

Even if not malicious, the effect is the same. Non-mainstream or auteur-driven films lose out to vertically integrated cinema–distributors. In saner societies with working policymakers, this behaviour would trigger antitrust investigations, fairer laws and independent commissions getting to work, to improve conditions. But the gritty work and results might not be Instagram-worthy enough for the present administration.

The consequences of this system are already visible in the marketplace, particularly in how critically-lauded Nigerian films struggle to sustain fair theatrical runs. Other auteur-driven films like Juju Stories (which picked up FilmOne distribution momentum after a favourable AFRIFF 2021 screening) and Mami Wata (announced for West African distribution by FilmOne at its Sundance selection stage) were both distributed by the major player. Despite strong critical acclaim, both titles experienced early drop-offs or off-peak showtimes in Nigerian cinemas. This prompted renewed concerns about the value of these films at home.

During the December 2024 box office battle, Mercy Aigbe’s Thin Line, distributed by Cinemax, faced alleged sabotage. Cinema staff supposedly redirected customers to other films. Toyin Abraham’s Alakada: Bad & Boujee, a FilmOne distribution (their second major holiday title), was performing strongly but wasn’t widely shown. Femi Branch publicly highlighted how some film merch and staff in cinemas seemed trained to push select titles, subtly guiding customer choices.

In early 2025, CEAN rep Patrick Lee responded that it’s all economic (read business) and that films with low turnout get fewer slots, rather than deliberate sabotage.

But when the system consistently penalizes Nigerian audiences, and occasionally sends them to other titles, trust in the model erodes. Also, Lee touched on the “technical difficulties” excuses at cinemas, blaming this on the high operations required during busy periods.

And part of the problem, as all the events show, may lie in how distribution is designed in the country. Many Nigerian distributors don’t have regional sales reps (ensuring that films are playing when and where they should), clear rollout plans, or marketing infrastructure, meaning that much of the promotional burden falls back on the filmmakers. One filmmaker I had a detailed conversation with this year, Mildred Okwo (La Femme Anjola), put it plainly, “Distributors don’t treat the films like theirs. There’s no ownership.”

Moses Babatope shares a similar concern but frames it differently, saying that too many filmmakers hand films over as if distributors were studios. “The distributor didn’t commission the film,” he said in the Nollywire interview, noting that without a dedicated marketing plan and budget from the start, the filmmaker ends up begging for patience or protection the system can’t afford to give. For him, every Nigerian film is an independent project and financing must stretch from script to marketing to screen.

While technically true that distributors did not commission most Nigerian films, this framing creates an imbalance. Distributors still earn a share of the gross box office (typically averaging around 5%, depending on the deal) yet often assume limited responsibility for positioning the film once it enters cinemas. In the quest for more footfall, there is an urgent need for them to act more like true partners than just middlemen. Even a uniquely marketed film like Red Circle (distributed by Nile), mostly handled by the producers, was toyed with at the box office. This isn’t just about filmmaker responsibility; it’s about transparency and accountability from exhibitors, which Babatope skirts. Moreover, this entrenches inequality. Emerging filmmakers without access to such resources are locked out, even if their films have strong artistic or audience potential. It continues to build Nollywood as more of a capital game than a cultural one. Course correcting needs to be done sooner than later.

There is also the issue of cinema managers overriding programming decisions based on momentary crowd demand, sometimes even switching scheduled films to more in-demand ones on the spot. Filmmakers have reported cases where their tickets were printed for a different film or screenings were cancelled last-minute to favour another title. In a conversation with another producer, they share, “My sister went to see my movie, and they started playing another film instead.” In another instance, “a friend bought a ticket to my movie, but it was recorded under another title on the receipt.”

How does one fight that when the weekly overview shows that no ticket was sold for the said film in that city?

For a business such as the film business that has a lot at stake for many players, a trustworthy body might be needed to independently serve as a watchdog of the industry’s box office activities. More assurances are needed for the future, where stakeholders can fairly learn and keep building for sustenance beyond settling for overflogged formulas.

As Wingonia Ikpi, a former content development producer at FilmOne, explains to me, the company once operated both as a production and distribution outfit under FilmOne Entertainment, before formally distinguishing its studio arm. “We were closely knitted across both sides,” she recalls, noting that their decisions were guided by commercial potential, data from past box office trends, and genre performance.

Yes, data-informed exhibitors need to manage costs in a dwindling economy. But some of these perceived new films—thrillers, auteur-driven, character‑dramas—don’t open like Hollywood blockbusters or star-led films. They thrive on buzz, cultural resonance, and word‑of‑mouth. King of Boys grew in such a manner. Most recently, it was The Herd. By holding films to first‑weekend standards alone, we set the industry up for failure. How do you develop a healthy audience for many other genres? How do you expand the audience’s palette?

Moses Babatope calls this Nollywood’s tragedy, whereby films that need time to breathe rarely get it. “Some titles require one or two weeks to settle,” he noted. But with bills to pay, cinemas rotate quickly, sacrificing the patient runway such films need.

And in some cases, audiences actually show up, but still can’t watch the film. Demand can’t be measured when access is obstructed. This reduces the credibility of “audience demand” as an equalising factor.

Filmmakers are asking for fair conditions. That means guaranteed minimum run in stable time slots, more transparency and reform from CEAN (Cinema Exhibitors Association of Nigeria). This can happen alongside government stepping in, might be extreme, like had been previously done in the US.

In the U.S., major studios like Paramount and Warner Bros not only produced and distributed films, but also once owned the cinemas. It wasn’t until 1948, through a ruling, that the Supreme Court forced studios to divest their theatre chains. This ruling was meant to restore fair competition and open up exhibition to more players.

If monopoly tendencies intensify, Nigeria might need a serious court case to course-correct. Moreover, Patrick Lee of CEAN once said that the filmmakers need to report these cases for proper investigations and resolutions. “We can only act on official complaints. Social media posts do not give us the authority to investigate,” he said.

Red Circle, for example, devised what one could call its own makeshift solution, encouraging people to take pictures and videos at cinemas and post them on social media. This helped to establish not just visibility but proof that their audiences were present at specific cinema locations.

When a film can be toyed with mid‑conversation, the producers lose revenue and the industry loses audience trust, most especially potential new audiences. Both filmmakers and even audiences may ask, “why try next time?”

Films deserve room to breathe. And audiences deserve to trust that if they walk into a cinema and buy a ticket, the film will play until the end credits. This breathing room further requires distributors who act as partners, not passive middlemen, as they both work towards filling the cinema seats. “Distributors need to see producers as partners on the journey. They need to see the film like their own baby,” Okwo suggests as a possible way forward, because it means the distributors sharing in the risk, and taking up the fight together along the journey.

The imbalance is deeper when considering runtime pressures. Some filmmakers shared that cinema operators discourage films longer than two hours, regardless of story demands. Chuks Enete (producer of Inside Life) notes, “I was told my film had to be under 2 hours or it wouldn’t be screened.” Another producer adds, “We had to cut the film from 3 hours to 1 hour 55 minutes before approval.”

And despite the buzz and premiere glamour, without consistent standards, everything can unravel. “Opening weekend is key. That’s when producers get the highest cut,” said Enete. If buzz from premieres is high, more screens may be granted. If not, a film might also get screens withdrawn.

Wingonia acknowledges that a film’s opening weekend does matter. “Every exhibitor wants to give the best slots to their own films,” she notes, but she also cautions that the deeper issue is structural. “We don’t have enough cinemas, and we don’t have different levels of cinemas—low-end, mid-tier—that can meet audiences where they are,” she explains.

“Maybe cinema is not really our culture,” I suggest, and Wingonia agrees. “We need to build that,” she replies, advocating for low-cost, community-driven ‘watch centres’ that could restore the collective film-viewing culture of the home video era. Fusion Intelligence piloted a community cinema experience in collaboration with some Cafe One locations. Worth seeing how the industry makes use of the path, with plans for expansion in the pipeline. Also, we need distributors who acquire low-to-mid budget films that they can market profitably. This distributor, backing quality films with strong word-of-mouth, has to be funded patiently.

At the same time, Moses Babatope sees Nollywood’s long-term prosperity less in cinema and more on digital platforms. His boldest prediction is that a local “Avengers-like” streaming platform will eventually dominate if players stop working in silos. While some previous Nigerian streamers like iROKOtv has failed and struggled, amid the challenges of pricing, piracy, and internet costs, observations have noted that the Nigerian audience is digital and mobile phones first, and they are ready to pay for a platform that is worth the price.

Ultimately, the industry’s dysfunction is worsened by harsh economic realities. Operational costs are high, cinema managers have their KPIs; audiences are fewer. “We can’t keep treating Nollywood like it’s a utopia,” Wignonia says. “Everything you see in Nollywood is a reflection of the country.” Her call is for more conversations, “not just press releases on hype,” but industry-wide dialogue about what’s broken and how it might be fixed.

Then cinema owners and distributors alongside the producers need to be aligned on the long-term growth of Nigerian films. “Seeing films as a collaborative effort is even beyond the creative lens. We should remember, it extends to the exhibition stage,” Okwo says.

While piracy and audience preferences play a role, what persists is a model that punishes risk-taking and non-formulaic storytelling. If the box office practices are not corrected, Nigeria will remain a market where filmmakers play defence from day one, and audiences rarely get to see something different on their screens.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.