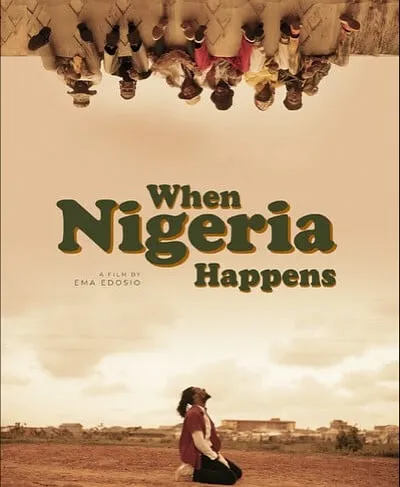

At the awards ceremony for the 2024 edition, Locarno Festival announced that its Open Doors program would dedicate the next four years to Sub-Saharan Africa. At the 2024 S16 Film Festival in Lagos, Open Doors Directors Manager, Delphine Jeanneret, built on that momentum through a workshop to guide filmmakers through the application process. That same festival, founded by the S16 Collective, also hosted a private screening of Ema Edosio’s When Nigeria Happens. A few months later, Edosio’s film was selected as the opening title of the Locarno Open Doors section, setting a historic stage for the Nigerian filmmaker.

As one of Europe’s most respected film festivals for independent filmmakers, its Open Doors program is a meeting point for producers, distributors, and co-production partners from around the world. By dedicating this four-year cycle to African cinema, Locarno seeks to foster sustainable film ecosystems, opening more opportunities for African stories to reach global audiences, collaborators and investors.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

Being part of it, for Edosio, meant instant visibility. “Even before I arrived, I had emails from distribution companies asking about my film,” she recalls. “Festivals like this are very intentional. They put your work out there so you can get a buyer, and at the same time, people start asking about your next project. It opens doors in every sense.”

Edosio’s storytelling style shows a slice of Nigerian life on screen, lives that are real, simple, and human. Her films capture everyday experiences that feel close to home for Nigerians and still easy for anyone to connect with. By focusing on her characters and their flaws, Edosio creates stories that feel true and relatable, both in Nigeria and globally. Her debut feature Kasala! brings to screen the humour and hustle of Lagos youth as four teenagers borrow a car for a party and land in unexpected trouble. Her 2022 film Otiti follows a seamstress trying to reconnect with her estranged father. Through the stories, Edosio has established that she wants to tell stories from the point of view of the average Nigerian.

Ema’s involvement in Open Doors guides her to another significant milestone in her career. According to her, When Nigeria Happens’ screening in Locarno was sold out, an achievement that meant more to her than just personal satisfaction. Colleagues and audiences congratulated her for pulling it off without a co-production partner, something rarely done on that stage. “That moment gave me confidence,” she says. “It told me my work could sit side by side with international films and still connect with audiences.”

“I had a strategy,” she explains. “I didn’t want to wait ten years before I made my films. I didn’t even understand co-production—most Nigerians don’t, because until recently our country had never signed an official [international] co-production treaty. So my plan was simple: use what I have to make films, and build my voice.”

Without the backing of major studios or large investors, Edosio pieced together the production for When Nigeria Happens using her own resources, experience, as well as past relationships in the industry. She drew from her background as a video journalist and documentary filmmaker to handle much of the work supported by a small crew of about thirty people. Co-produced by Nigerian-based companies Nganda Cinema, 8th Day Productions, including Edosio’s production company Citygates Film Production, Edosio also collaborated with choreographer Qudus Onikeku to bring as much real dance interpretation into the story.

Ema Edosio had already made films that travelled before When Nigeria Happens. Kasala! (2018) screened at Durban International Film Festival in South Africa. Followed by a Netflix licensing that opened it up to a whole new audience outside Nigeria. But finding success abroad also highlighted the struggles that exist back home. When an independently auteured film travels internationally and finds an audience, it proves that the talent and stories exist — but the systems to sustain them at home often don’t. The contrast becomes clear: while festivals and global platforms provide visibility, appreciation, and critical support, many similar films in Nigeria struggle to get screened or even noticed.

Her journey makes it clear that the challenge isn’t creativity, but access and opportunity. In Nigeria, independent filmmakers often face a wall of challenges: small budgets, limited distribution channels, and little to no marketing support when they go theatrical. Even when audiences are eager, films like hers risk being drowned out in a market dominated by mainstream titles. Still, Edosio insists that there is space for all kinds of stories. “It’s just like music,” she explains. “Afrobeat, Fuji, Highlife—they all have fans. Film is the same. There are audiences who want depth, who want something different. We just need to reach them.”

Festivals, she argues, are one way to bridge that gap. They don’t just provide screenings but also act as hubs for funding and collaboration. At Locarno, she began talks with potential co-producers for her next film, proof that one strong festival run can be the cog that turns the wheel of a filmmaker’s trajectory. “Film festivals level the playing ground,” she says. “They create a space where someone like me can sit across from Netflix or a European producer and be taken seriously. It’s not about what collateral you can bring to a bank. It’s about your story and your talent.” According to a 2023 Deadline story, Edosio is writing and directing Bisesero: A Daughter’s Story, a pan-African drama set against the backdrop of the 1994 Rwanda genocide. This film will focus on the Bisesero Resistance, where Tutsi villagers defended themselves against Hutu militias.

Perhaps the most important lesson from her festival journey has been how Nigerian stories resonate far beyond their borders, a similar thought that has been voiced by travelling filmmakers Dika Ofoma and James Omokwe in their respective interviews with What Kept Me Up. She vividly remembers a woman in her sixties weeping after watching her film. “These were boys dancing on the streets of Abule-Egba in Lagos, speaking English, and here was this European lady crying, thanking me for telling that story,” Edosio says. “That’s the beauty of cinema. You can take something so local and make it universal.”

Co-written with Bayo Oduwole, When Nigeria Happens tells the story of six young dancers in Lagos, Fagbo, Pokko, Lighter, Movement, Colos, and Poppy, whose shared love for dance keeps them hopeful amid everyday struggles. Their bond is tested when Fagbo’s mother falls seriously ill, forcing him to choose between his passion and family responsibilities.

The reception at Locarno also confirmed what festival programmers had been saying during panels: there is real curiosity about African films, though access has always been limited. Among the African feature films screened in the Open Doors section this year are Ancestral Visions of the Future (Lemohang Mosese), Le rêve de Dieu (Fousseyni Maiga, Mariam Kamissoko), Nome (Sana Na N’Hada), Omi Nobu (The New Man) (Carlos Yuri Ceuninck) The Bride (Myriam Birara), Une si longue lettre (So Long a Letter) (Angèle Diabang), and Vuta n’kuvute (Tug of War) (Amil Shivji).

For many programmers, Open Doors provided their first chance to engage directly with a curated slate of works from the continent. “I would walk through Locarno and people like major festival programmers would hand me their cards saying, ‘When your next film is ready, send it to me,’” she recalls. “It’s not that they’re just now opening up; they’ve always been curious. Now there are more films speaking the language of festivals, and programmers are excited to share them with their audiences.”

This is why she believes Nigerian filmmakers must see festivals not just as optional extras but as alternative funding and distribution systems.

For younger filmmakers hoping to follow this path regardless of their technical sophistication, her advice is both practical and encouraging. “First, focus on your voice,” she says. “Don’t chase festivals by trying to copy what you think they want. Just know what you want to say, and say it well.” Also, she stresses that rejections are part of the process. “You’ll get a lot of no’s. But each no teaches you something about what programmers are looking for, and how to translate your story so it connects globally. Keep creating, keep applying, keep building that muscle.”

Technology, she adds, has made the process more accessible. “AI has leveled the playing field,” she notes. “You can use tools to polish your applications, put your thoughts clearly on paper. Just apply. There’s such a hunger for stories. And when you finally meet that one programmer or producer who gets you, you’ve built a relationship for life.”

Ema Edosio stumbled onto the path of filmmaking, a world she never fully planned, but she kept making films. “If I had waited for the perfect conditions, I wouldn’t be here. Festivals like S16 and Locarno showed me that our stories are not just valid, they’re needed.”

When Nigeria Happens screened at 2024 S16 Film Festival, Locarno Open Doors (Switzerland), Mostra De Cinemas Africanos (Brazil), Ake Arts & Book festival, Ibadan Indie Film Awards, Oslo Films From The South (Norway), Film Africa Festival (London), Afrykamera Film Festival (Poland), The Art Film Festival (Russia).

When Nigeria Happens is available to stream on emaedosio.com, with a required fee for access.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.