In the past few years, foreign interest in and funding of Nigerian cinema and movie making has ticked up in ways that previously felt unrealistic to even plan for. Much of it can be attributed to the absurd wealth of narratives that can be gleaned from Nigeria’s endless lore by foreign enthusiasts. The other aspect of it is the economics. Buoyed by its large and still growing content-hungry population, Nigeria’s market has become too lucrative to ignore now and especially for the future. When you factor in the impressive work Nollywood has done in ensuring that Nigerians love homemade content as much as they love foreign ones and you have a market that just can’t fail. Netflix, Showmax, and Amazon are just a few of the big players around right now in a field that will undoubtedly expand.

‘Atlanta’ Season 3: The Highs, Lows and Nigerianness of Prestige TV

‘Atlanta’ Season 3: The Highs, Lows and Nigerianness of Prestige TV

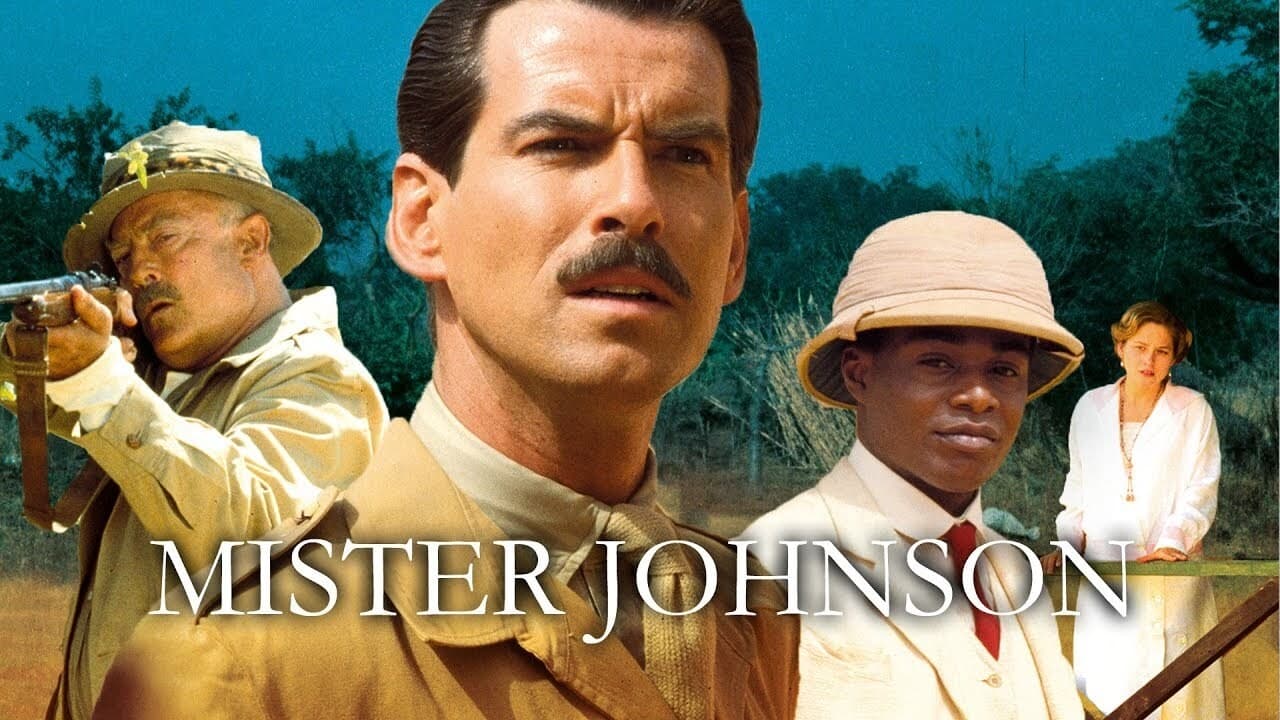

With this expansion will naturally come a creative sharpening, critical recognition and most importantly, commercial largesse that Nollywood sorely needs to scale new horizons. But there is nothing that goes for free. As Nigeria accrues these benefits, it must remember that there will be an interest by foreigners in telling our stories. Yes, I know they’ve always done that anyways, but now, we’re not just an unwilling audience or unwitting characters. We can tell our stories better and indeed can command enough nous to guide how our stories should be told, too. It is important that this moment unlike those before it is recognized and seized. One such failure in our past is Mister Jonhson the first Hollywood movie shot on location in Nigeria and failure under review.

It all depends on who you ask, but the question of why we make films are expected to be as concrete as the mind can fathom. To record memories or inspiration. To ensure that people make money (yes, I am referring to the entire thing Marvel has going on). To keep the business of filming going. To connect with kindred souls. To repel not-so-kindred ones. Or simply to tell stories. Stories, my friend. The narrative. The plot. It’s all there in the film. Watch it! But away from using story to justice every piece of motion picture, we must ask ourselves why. Why tell this story? Of what use is telling this story? For Christ’s sakes, Mr. Beresford, why does this story exist?

It was against the backdrop of these questions and answers that I watched Mister Johnson with not a small levy of bias in my heart. I was determined to find the meaning for this story. It had to have practical uses. I know it is hypocritical of me to ask a work of art to present the credentials of its worth in tactile, real-world terms because I haven’t asked this of any works in the past and I have no plans to ask it of any works in the future. Furthermore, it is an exercise in futility, but I feel bravely nihilistic so come with me anyways.

You will most probably enjoy the trivia more than you will the uppity critique, so let’s reel out the particulars. Mister Johnson is a 1990 film adaptation of Irishman Joyce Cary’s 1939 novel of the same name. Directed by Australian Bruce Beresford, the film shows the life of the idiotic, exuberant yet ironically clever stereotype of the African person that is Mister Johnson (Maynard Eziashi) a clerk in employ of the Queen’s representatives in Fada, Northern Nigeria who leads the life every white colonist thought their colonial subjects lived. He lived in the kind of excess that eventually warranted debt on the less than wealthy. He lied. He stole from the purses of those he worked for a la the colonial apparatus, Sargy’s shop and he fails at his attempts at trading. He marries a wife he won’t beat or can’t beat, is obsessed with British culture and considers his native Nigerian one backward. It is said that reading the book Achebe was so annoyed, that it steeled his resolve to write his own books to showcase an authentic Nigerian perspective.

It is therefore in Achebe’s works that we will find the perfect juxtaposition for this critique. First is in Achebe’s characters: all complex like the brash he-man Okonkwo (Things Fall Apart) and the idealistic cynic Odili (Man of the people). In Achebe’s characters, we find Africans with dignity. They are not particularly good people. In fact, rarely does an Achebe character achieve the ideals of the society he so wishes to save. But Achebe makes them idealistic at the least because to have ideals is to be human truly. And to be human is to have qualities that redeem us. Human qualities like Okonkwo’s enterprise and Odili’s honest introspection. Intrinsic human qualities like dignity. Not some, not man, not all. Just dignity. And this is something that Mister Johnson lacks. My god, we learn nothing of his origins because he calls England home. He has no regard for the venerable local leadership of Fada in the Emir (George Menta) and the Emir’s Waziri or Vizier (Femi Fatoba) but fawns over the degenerate drunk, barely literate and rabid racist that is Sargy Gollup (Edward Woodward). An opportunity was lost to do right by this character by showing us the way he went about his attempts at being a tradesman, but they don’t. You start to think the reason they didn’t was that he wasn’t attached to the hip of a white man and his story wasn’t important otherwise. These little, maybe big but glaring refusals to explore Mister Johnson as a human being make it hard to identify with him. No audience can. His death drawn out in some dramatic philosophic breath is not enough to conjure sympathy. I hissed when he died. Hissed and rolled my fucking eyes.

Wings, Guns and Planes: When Cinema and Military Join Forces

Wings, Guns and Planes: When Cinema and Military Join Forces

The Hughes Brothers Deliver Timeless Commentary on the Complicity of Everyone in Societal Decay

The Hughes Brothers Deliver Timeless Commentary on the Complicity of Everyone in Societal Decay

In fact, you could make a case that the character just serves to inform the perusing public that the African regardless of exposure to British virtue will still rely on his baser African vices when he needs to. In my own opinion, the most undignifying thing done in the entire thing is the deliberate attempt by the storytellers to conjure some dignity for the character at the end of the film. And their genius idea is to have his favourite Briton Harry Rudbeck (Pierce Brosnan) kill him. With this, they try to confer on him some worth but it is too little, too late.

It is not that the character lacks realism. We do have many a human that lacks dignity. And the story of the self-hating African is one that we colonial and postcolonial Africans can sadly relate to. But there’s hardly any realism in a character that doesn’t have any redeeming qualities. No standout thing going on for him beyond the mildly racist stereotyping of the script and source material. Of what use is this to me? Of what use is such a character to anyone, really?

And then, there’s the story. And we must all remember that the story is king. Everything else must fit into the framework of the story. Call it narrative, plot, story – anything really. It is paramount. But one thing (amongst many others) can make or mar a story. Spoiler alert: it mars this one. That thing is the relevance of a story to its audience. We’ve already discussed the utter uselessness of the static titular character, but Mister Johnson fails to deliver a story that makes any sense to any Nigerian seeing it. Not only does it gloss over the impact of colonialism in creating marionettes like Mister Johnson, but it also doesn’t even bloody confront the concept. To the African watching Mister Johnson, what does she see? A story by the colonialist to assuage the feelings of the colonialist. She sees the story of the African who is only good for the odd bout of cleverness, who is ruled by base passions and greed, whose best work is done working under the watchful gaze of Her Majesty’s dutiful white representatives. He sees a film that cleverly pits the African woman as played through Bamu (Bella Enahoro) Mister Johnson’s wife against Celia Rudbeck (Beatie Edney) Lord Rudbeck’s wife. Bamu marries Mister Johnson because he can afford it and nothing else. She even routinely leaves in the company of her business-minded father Brimah played by Nigerian theatre pioneer Hubert Ogunde whenever Johnson defaults on his payment. She is a distant, perfunctory and impassioned wife whose only minute of affection towards her husband is offering him his last meal before capture and eventual death. Celia on the other hand is different. A British girl with decent prospects who out of love marries an up-and-coming civil servant. She even moves out to “bloody West Africa” to be with him. She looks at him kindly and their coitus is hurried and hot like that of young starving lovers.

Let’s call on Achebe again. Let us look at Umuofia in one fell swoop. What makes Umuofia a real place? What makes it so different from this visage of negativity and poverty that Joyce Cary and later Beresford bestow on Fada. They are both fictional places, yes and as such, you may think the writers shouldn’t be blamed or upheld for using the freedom of imagination that fiction allows. But that would be ignoring that like Umuofia, Fada is constructed on the real-life experiences of both authors: Achebe as an Igbo man and Cary and Beresford as outsiders to the African circle. If instead of the African complex society that Achebe writes about with Umuofia, Cary only sees a regressive, self-serving one, one has to question the very need for the story and indeed, all of the work.

What this movie however lacks in story and character relevance, it makes up for in production values. Watch the thing. It’s light years ahead in terms of cinematography, casting, location management and performance than much of what we have in the Ajah-Lekki-Victoria Island-Ikoyi subset of Nollywood that dominates the space today. One thing that struck me was the usage of extras for the road-building scenes. The sheer number made each scene so rich, so alive – a visual feast, really. Gathering those extras from the National Theatre in Lagos in South Western and ferrying them across to Toro in faraway North East Nigeria where it was shot was not easy work. That kind of grit and willingness to spend right is sore missing even in the lavishly funded projects of today. In another timeline, Mister Johnson would have ushered in a new level of technical excellence in Nigerian cinema and set a template for how foreigners should approach Nigerian stories, but it didn’t and we can only dream of certain things, you know? Well, not just dream. We can however look at Chinualumogu as a template for how it should be done.

Finally, I’m currently reading a book by John Green. It’s titled “Looking for Alaska”. The main character is Miles and he hates conclusions in essays because they are just summaries. I agree with him.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows with Google calendar.