In For Maria: Ebun Pataki (2020), a pediatrician tells new mother Derin, “Babies cry. It’s what they do,” when she questions her infant’s incessant tears. The cries disrupt Derin’s sleep, heighten her panic, and fray her nerves, as if the baby exists to unravel her peace. And when she attempts to comfort the child, the crying persists, only softening in the arms of her husband. This is the same predicament Bolu finds herself in Out In The Darkness after the birth of her second child.

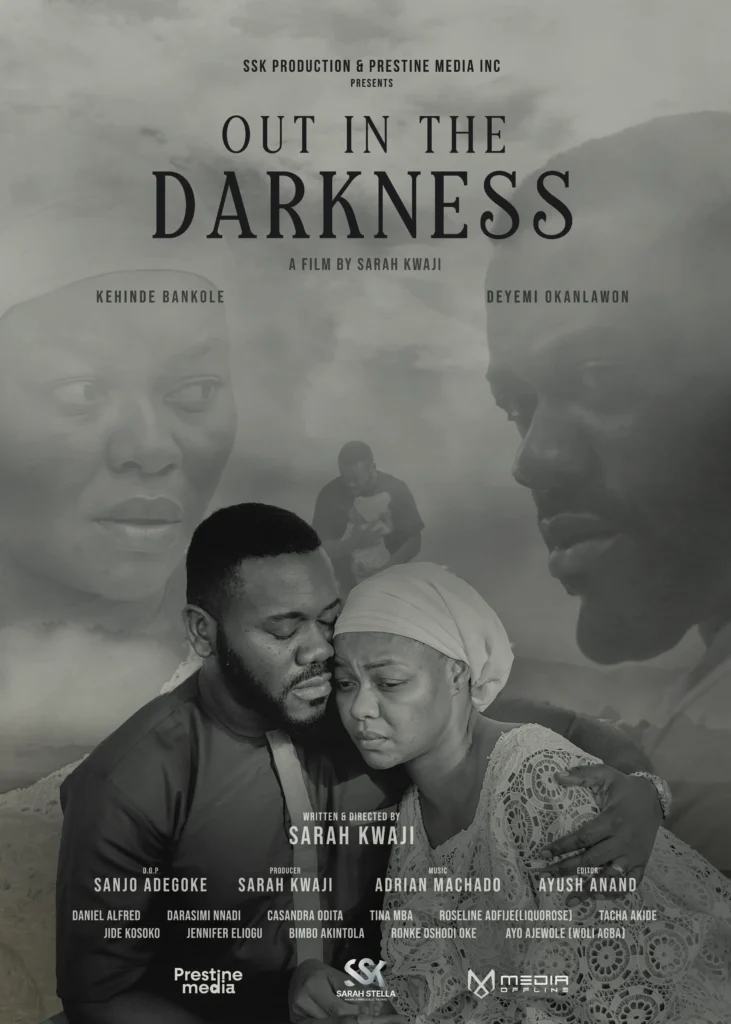

Out In The Darkness explores a woman’s harrowing journey through postpartum depression and psychosis. Her baby cries all the time, and Boluwatife (Kehinde Bankole) takes the crying personally. Although not her best efforts, Bankole’s portrayal of Bolu is moving, capturing the visceral torment of a woman at war with her own mind. Deyemi Okanlawon (Sista), as Nasiha, brings a tender support to the role of a husband grappling with his wife’s alienation. He is steadfastly present as a father and husband, but his inability to connect with his wife’s experience underscores the isolating nature of postpartum crises.

This film wants the audience to know that there’s nothing rational about postpartum depression. For women like Derin and Bolu, educated and privileged middle class, nothing prepares them on how to handle a situation where they would hate their own baby to the point of wanting to kill themselves or the baby. So the strongest commentary from both films, I believe, lies in their refusal to propose a singular explanation for the cause of postpartum crisis for new mothers.

Where Out in The Darkness diverges, however, is in its sociocultural lens, particularly how Bolu’s mother (Tina Mba) and her mother-in-law (Cassandra Odita) are both convinced her affliction is spiritual, and her mother drags her to a white garment church where she sleeps for days. Can we blame them? In a Nigerian context, where mental health struggles are often filtered through a spiritual prism, their response reflects a broader societal tendency to seek supernatural explanations for psychological issues such as depression.

As a debut director who also penned the screenplay, Sarah Kwaji’s ambition to probe postpartum psychosis and throw it into the spotlight is commendable, especially given there are only a few Nollywood films on that subject. But her execution of the narrative feels like a half-drawn sketch. Unlike For Maria: Ebun Pataki, which wove its protagonist’s despair into a taut narrative, Out In The Darkness stumbles into a quiet fuzziness with its sluggish pacing. The psychological torment experienced by Bolu, leaning on the melodramatic, lacks the sustained intensity needed to jolt us to grasp the profundity of postpartum psychosis.

Kwaji’s screenplay shows a writing eager to communicate the psychological horror of postpartum depression, but in the eagerness and earnestness of its ambition, it seems to overstretch this portrayal even in moments where it could have been more subtle. While starting with the necessary ingredients for a topical film, it gradually takes on a documentary-like feel in its latter stages, ultimately lacking the spark needed for a cohesive story that truly haunts after the credits roll.

However, in the wider sociocultural conversation, Out in The Darkness gestures toward urgent questions about maternal mental health in Nigeria, where stigma and silence often shroud postpartum struggles. The film’s depiction of Bolu’s crisis, against the backdrop of her family’s cluelessness and misunderstanding of her situation despite their support hints at the systemic gaps—limited maternal mental health awareness, cultural beliefs—that exacerbate such conditions.

Out In The Darkness is a film with a heart in the right place but a grip too loose to hold its weighty subject. For all its good intentions, the film is a seemingly important but inefficient echo of the postpartum nightmare it seeks to illuminate.

Out in the Darkness premiered at NollywoodWeek (NOW) Film Festival 2025. It opened in Nigerian cinemas on July 4.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- Is Bolu’s mum okay? Instead of her to focus on her daughter who’s the main reason they came to the church, she is concerned that Nasiha (a supposed Muslim) is not kneeling down.

- Babies born to mothers suffering from postpartum depression are not even helpful. Can’t they like do their baby stuff but read the room via the emotional bond with their mother? L.O.L

- Speaking of babies, I love the irony in the nightmare scene where Bolu is in the labour room and is visibly worried that her baby is not crying, while in reality the baby’s cries drive her crazy.

- Not a big deal but little Zara (Darasimi Nnadi) opening her little arms for her grandma to hug her when it’s supposed to be the other way is quite awkward. But anything Darasimi does is forgivable by me.