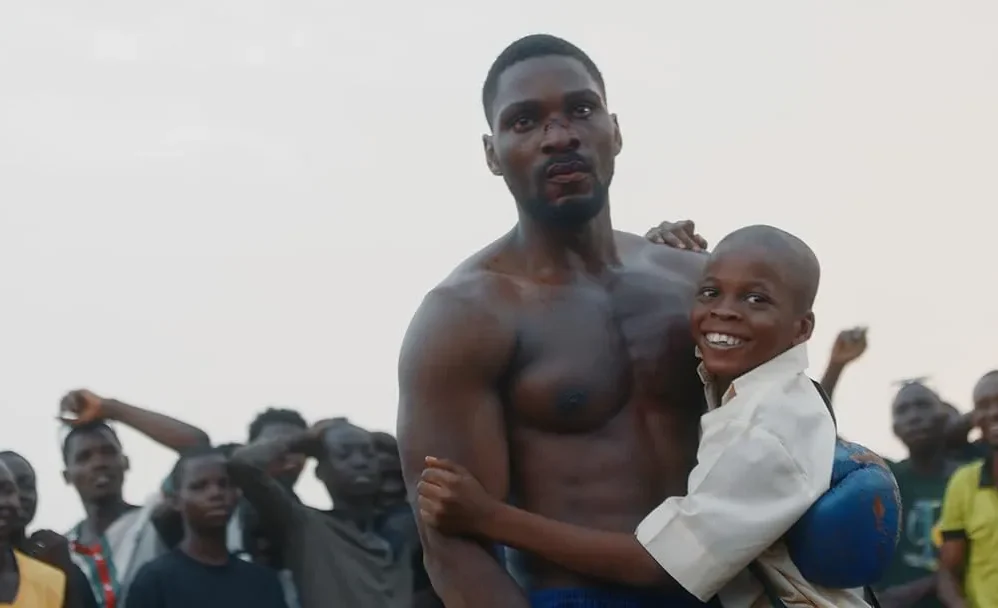

Suky opens in a boxing ring, where Adigun (Tobi Bakre) is instructing a group of young fighters with the assured discipline of a man who has survived too much and seen too little change. Among the onlookers is a boy, perhaps ten, his eyes absorbing more than he understands. This boy is Sukanmi, the titular character (Suky). We soon learn that Suky is Adigun’s son. Played in his younger years by Malik Sanni and as an adult by James Damilare Solomon, Suky becomes a character whose stillness is more expressive than dialogue, and whose trauma, like his fists, lands heavy.

Bakre, whose performance as Adigun barely spans the first twelve minutes of the film, stays until the end. We’ve seen him embody gritty roles in Gangs of Lagos and Brotherhood, but here, as a haunted father hiding pain from his child, he balances warmth with weariness. His relationship with his son is authentic—there’s a quiet, believable tenderness in the way he explains that sons shouldn’t worry about fathers.

In the early scene before Bakre’s Adigun is killed, his murderer, Sledgehammer (Philip Asaya), has a brief chat with his son. “You know, Suky, a man who cannot keep his word is a dangerous man. No, Suky, look at me when I’m speaking to you. Your father is a dangerous man.” The dialogues are definitely not the best we’ve seen in Nollywood, but they stand out, they carry the weight akin to them.

After Adigun is killed by the feared Aje Gang—though we’re never told why, except that he’d bridged a contract—young Suky’s life unravels. He is taken in by a lawyer, whose presence in the story is more convenient than clarified. Soon, the film leaps forward in time. Suky is now older, more muscular, and almost completely mute. This near-silent adult version, portrayed by Solomon, carries the weight of the film’s latter half with a performance that is nothing short of magnetic. It’s a rare Nollywood choice to centre a protagonist with so few lines, but Solomon turns this constraint into strength. His eyes communicate grief and rage. His movements are deliberate. And in a genre that often leans on verbosity, his quietness feels revolutionary. This, in its entirety, is the apex of the film. In Solomon’s earlier years, Malik Sanni brings his own grit. Rarely does a child actor surprise me in a Nollywood film without overacting or underacting. Sanni’s young Suky is near perfect. He knows his assignment and delivers it with apt.

It only makes sense that silence itself becomes a major character in this story, living through Suky. A boy has just witnessed the death of his father, stabbed in the neck only because he hadn’t succumbed to defeat. Trauma wears many faces in reality, and in Suky, it is silence. Silence has served as a tool since probably the invention of storytelling to convey emotional depths, build tension, or allow the audience to sit with the gravity of a moment. If effectively done, silence is louder than noise. Consider Keanu Reeves’ John Wick in the titular neo-noir action thriller film series. Through silence, viewers are invited to enter the soul and motive of the character effortlessly.

Many things work towards establishing an intimate father-son relationship between Adigun and Suky, and one of them is religion. The play of religion in this film makes it stand out, and Islam is at the core. Suky, like his father, is a devout Muslim. This sets Suky apart from similar Nollywood thrillers. Religion is often sanitised in such stories, and when it isn’t, it’s rarely Islamic, or Yoruba Islamic. But here, it adds layers of realism. It gives Suky’s choices context and weight. This is who he is, not just what the story needs.

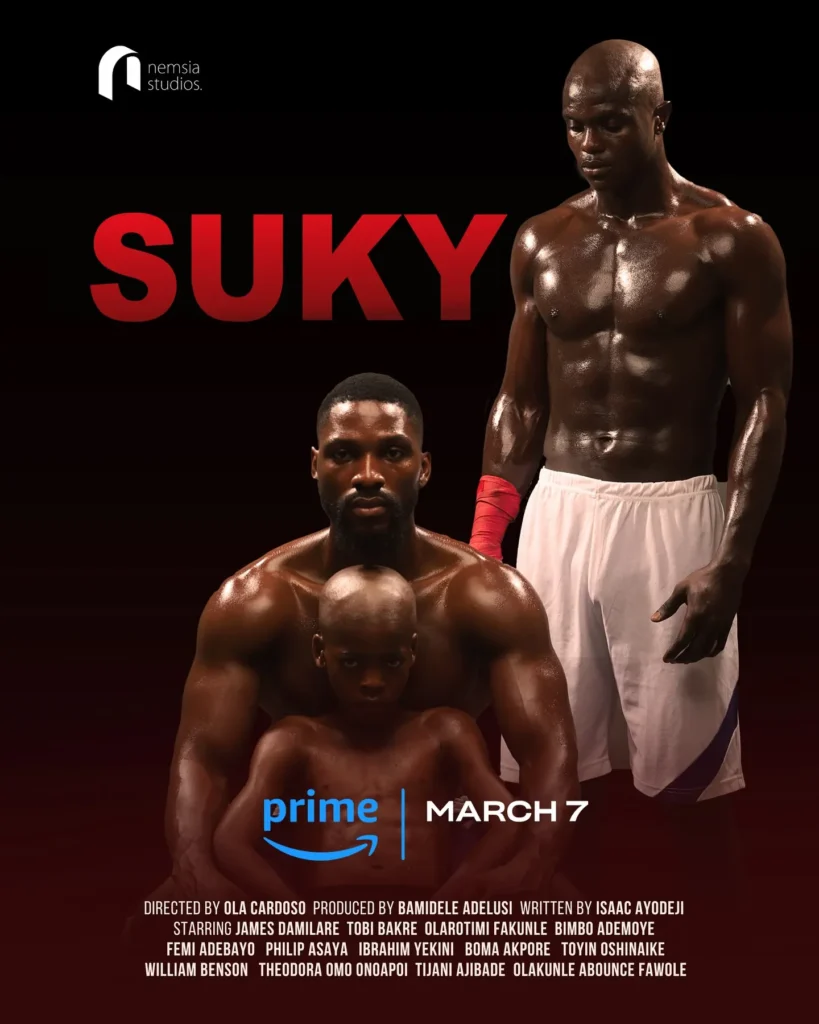

Directed by Ola Cardoso in his debut (having transitioned from cinematography), Suky initially promises a brooding, character-driven story rooted in a father-son bond, grief, and revenge. But as the narrative broadens to include prison systems, political corruption, and an underground fight club, its sharp focus begins to blur.

One might think it doesn’t matter, but the room where Suky grows into an adult and starts having his own nightmares has walls littered with wallpaper and stickers. By the corner of his bed is a guitar. These details hint at a fuller personality, a man who once had other interests, something probably far removed from the rest of the noisy world. But the story doesn’t follow through. It gives Suky a room, not a life. We know nothing of his existence outside vengeance, nothing of his interests. And that flattens him to some extent.

Much of Suky’s outer world takes place in a grim prison, where the titular character discovers an underground fight club. This space, filled with makeshift rings and a hierarchy ruled by violence, is where he begins to reclaim the strength that was stolen from him. The fights are brutal, if sometimes over-staged, but it’s the internal war—a survival mechanism—that gives these scenes gravity. That said, we don’t know why this fight club exists or the plausibility of it, or why it’s political outside of being an entertainment for the powerful. The story gestures at larger systems but doesn’t show its work.

Cardoso’s direction, even as a first-timer, is ambitious. Yet it’s in the writing that Suky falters. Isaac Ayodeji’s screenplay sets up questions it doesn’t really answer, tensions it doesn’t resolve. One is left to wonder who exactly the Aje Gang are, and what real relationship they have with Adigun. The film starts a political subplot after hinting at collusion between government figures and prison bosses, and drops it almost immediately, forgotten. And you would think that Sledgehammer is some demigod (a Nigerian Maui?) who doesn’t age after all these years, when the film is not a Sci-fi or melodrama. These lapses chip away at the credibility of the world the film painstakingly builds.

Then there’s the climax—nearly drolly unbelievable. When you leave too much for the audience to figure out, you might just haven’t done a complete work. This is fucking prison, and to have been brought here on some political terms means it is not a privately run establishment. Prisons aren’t privately owned organisations, not in Nigeria at the least. Marshall’s brutal demise serves only to portray a heavy-handed moral lesson, conveniently sacrificing narrative coherence in the process. The absurdity of Suky’s trainer, a fellow prisoner, assuming authority over the prison highlights the story’s blatant disregard for plausibility. Things don’t pan out this way in reality, and the writing does little to support them.

Still, despite its narrative shortcomings, Suky has moments that make me smile. The fight choreography, while occasionally overstated, is well executed. The sound design is effective. Fisayo Adefolaju’s score complements the emotional beats, though it leans too often into sentimentality.

The cast brings a familiar level of professionalism to the project. Although Bimbo Ademoye’s Dr. Simisola is underutilised, she manages to bring a subtle sensuality and softness that briefly offsets Suky’s hard world. Ibrahim Yekini’s Ijaya is one of the more compelling supporting roles. Philip Asaya (Kill Boro) delivers an average performance, though his character—like many others—is never fully explored. Femi Adebayo (King of Thieves) is surprisingly underwhelming as Senator. We’ve seen him do better.

There’s something deeply promising in this project. It’s not every day that Nollywood casts a relatively unknown actor like James Damilare Solomon in a lead role, and even less often that it lets him carry the film through gesture and presence rather than words. His performance suggests a career worth watching. If there’s justice in this industry, Solomon will be offered more—and better written—roles. What he brings to Suky is subtlety and fierce vulnerability.

It’s clear Suky is a film of great parts that do not quite form a whole. It lingers not because it concludes satisfyingly, but because it dares to try something different—even if it doesn’t quite succeed. For a film that opens with a child learning to fight by watching his father, its biggest lesson might be that silence can be just as powerful as sound, and that the stories we almost tell can be as revealing as the ones we do.

Suky premiered March 7 on Prime Video.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- Doctor Simisola isn’t the only person in a toxic relationship with Marshall. That cute black cat is also suffering from Marshall’s toxicity. Just look in its sad eyes and you’d know.

- Boma Akpore’s character is a witness to the old saying “Empty vessels make the loudest noise,” cause man, what’s all that?

- Film role aside, Malik Sanni needs an award for most truant student with the best skills at jumping fences. There’s no way that isn’t natural to his person.