Working as a co-producer on the most decorated Nollywood film of 2021, Eyimofe— a cheese pick at The Annual Film Mischief— Adé Sultan Sangodoyin shares stage-by-stage lessons that participating filmmakers can learn from the Esiri Brothers-directed film. Sangodoyin is no stranger in Nollywood; he has worked in various capacities—assistant director (Omugwo), production assistant (October 1) and art director (The CEO)— across multiple Kunle Afolayan projects.

In a statement director Chuko Esiri reiterated during a Q&A session at the opening night of The Annual Film Mischief (Lagos edition), Adé Sultan Sangodoyin also shares similar memories as to how the creative partnership happened, “when they came home to shoot Eyimofe, naturally you look at people you know on ground, with experience, who also share the same filmmaking sensibilities as you in order to have as easy a shoot as you can.” In other parts of the brief interview, Sangodoyin explains the power festivals could possess in the near future for filmmakers, while also blowing the horn of some current non-mainstream Nollywood filmmakers.

Festivals don’t exactly function as an alternative form of distribution. They serve as conveyors. And presently, I don’t believe it can function as that yet, given where we are with things. But as they begin to grow in size and credibility, you may have sales agents/distributors from all over attending. I don’t think that’s far at all.

1. What can the participating filmmakers at the Annual Film Mischief learn about the making of Eyimofe, from pre-production to exhibition stage? Any particular lessons to share?

Within the pre-production stage, it’s important to have a fullness of commitment to your vision. A lot about filming brings you to the feet of compromise, but you should never set out that way. Believe the infinite beauty within your mind can be captured. Write the story to its core truth and representation. It took Chuko (Esiri) four years to have a final draft of the script that became Eyimofe because he kept developing it, seeking a balance between space/Lagos, characters and what he wanted to say. We couldn’t have filmed the story anywhere else but within locations like Adeniji-Adele, Obalende, and Mushin, in order to create a setting that’s starkly true to the marginalized within an already marginalized group and also presenting the other dichotomy of the Island, and how those two halves often interact. The casting process with the help of our casting director was also an arduous one. I joined the production around this time and it was very taxing but rewarding. From stepping out of the familiar, getting actors who had only worked on stage to leaving Lagos and traveling to Ibadan to cast students at the University there, to screen testing and then contrasting actors for visual compatibility, etc. Ultimately, this stage had to do with honesty to one’s efforts and remembering that when you face a wall, you need to turn into your internal individual industry.

Principal photography had a lot to do with knowledge, application and the right team. I think the practical dimensions to filmmaking are the same in most places, in terms of what constitutes crew positions, equipment, securing locations, etc. What differs is the creative depth and spread you bring to the forging of your story and its application on set. It’s important to have an expansive knowledge of the world of cinema and its language, which is what impressed me with the Eyimofe crew: how the script, production design, the sound of Lagos and visual language and the choice to shoot on film all existed in one coherent and complementary whole. I was particularly taken by Arie and Chuko’s directing of the actors on set. How the techniques they employed stimulated behaviour i.e. actors behaving like the characters as opposed to a mere staging of performance. This knowledge in all of the aforementioned departments and aspects of filmmaking is something filmmakers need to seek and continue to learn. You can buy books on Story, Directing, Directing Actors, Editing, Production Design and watch film tutorials. You begin to understand the films you watch with their initial intention and your references and creativity become richer. Knowledge is a lot more accessible today than it was a decade ago. I think our evolution as filmmakers and the journey to mastering the craft begins down this path. When you do this, you see your story with evolved eyes and it reflects in your work.

There’s also the aspect of working with people who trust and support your vision. A team of sponsors and producers who have a centered and globalized outlook on cinema and how committed they are to the success of your film. That’s essential for the release and exhibition stage.

2. In April, Eyimofe will be available as a Criterion release which is mostly accessible to people abroad. How soon would hopeful Nigerians living in Nigeria get to see Eyimofe again?

Hopefully sooner rather than later.

3. Looking to blow the horn of other filmmakers who we might not even know about yet. What are the best non mainstream/low budget Nollywood movies you saw last year?

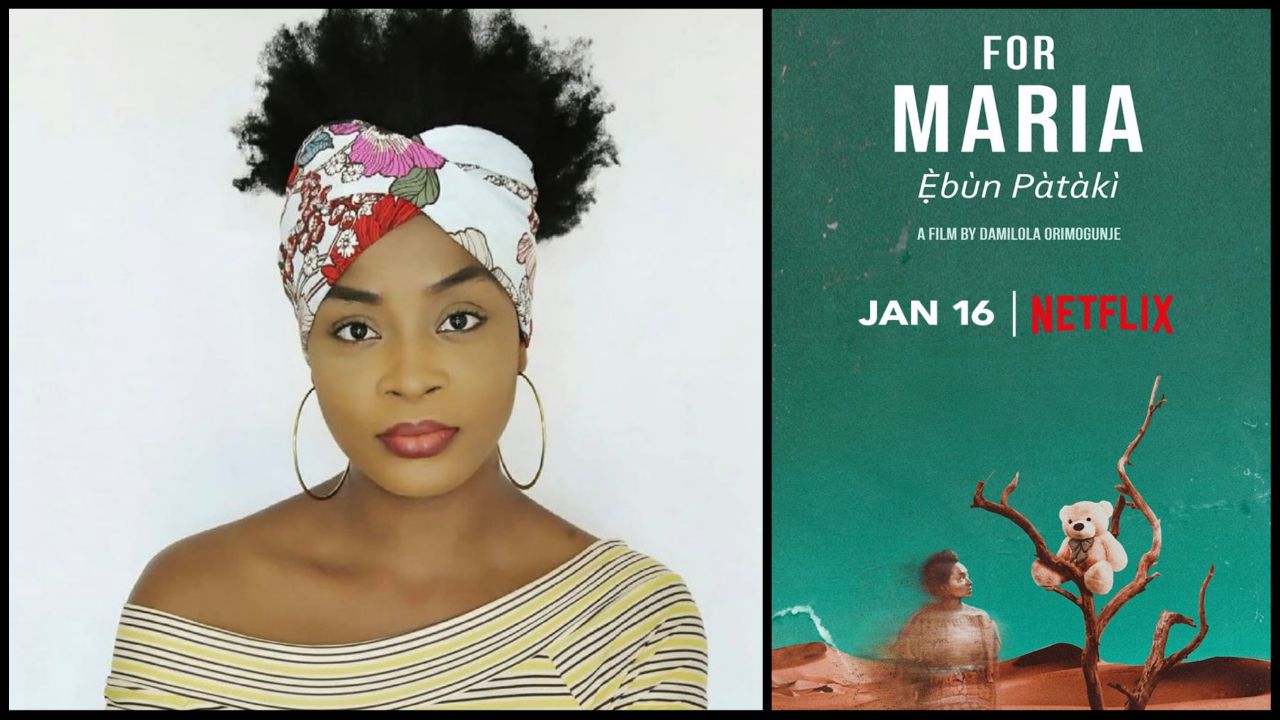

‘For Maria Ebun Pataki’: 6 Questions with Co-Writer Tunray Femi

‘For Maria Ebun Pataki’: 6 Questions with Co-Writer Tunray Femi

I liked Damilola Orimogunje’s For Maria: Ebun Pataki a lot. His references are clear, but his individuality as a filmmaking voice also stood out. Olive Nwosu’s Egungun felt like a film put together with certain constraints, but I liked how it consciously challenged convention, both diegetic and structural.

4. How much space do you think is there for independent voices and minds at the moment, this delicate stage of Nollywood?

I think the space is infinite and it’s really interesting to see the varied voices that are emerging. I’m a little uncomfortable with the way people bottle the whole space i.e. calling it Nollywood. There’s a specificity to what Nollywood films feel like; it’s well aware of its identity and it’s done really well as a form. However, to understand how diverse we are as creators, a look at the history of Nigerian cinema takes you to the Golden Age era with filmmakers like Ola Balogun, Adeyemi Afolayan, Eddie Ugbomah, Moses Olaiya and then the VHS days of Alade Aromire and then Nollywood. At the moment I feel we have a good number of emerging styles, each existing within the integrity of its references, the filmmakers’ voices, commercial intentions and functions. I think Nollywood already has an established following, while those of the others are beginning to swell. What encourages me about all this is the improving proficiency of technique and a gradual awareness of story across the board. I think we have to create from the depths, what is true to our spirits. I think we can co-exist and that’s evident with the successes at Criterion, Locarno, the presence of Netflix and Amazon in Nigeria and potentially a few more incoming opportunities for all.

5. The Surreal16 directors kicked off their S16 festival in 2021. Now, we have The Annual Film Mischief, a festival for low budget quality Nollywood movies. Is the influence of festivals starting to rise and what are your thoughts on festivals as an alternative distribution channel for young filmmakers? And how far do you see this going in this stage that Nollywood is in?

The joy of every creator is for their films to be seen and appreciated on the big screen. Film festivals like these offer that for young filmmakers who do not have enough leverage yet with distributors in Nigeria to exhibit their pictures in theaters. Festivals are also remarkable for celebrating, creating and nurturing the growth of a country’s cinema culture and bringing to the fore its dynamism. You get to watch different approaches to cinema and I like that. The reception at these festivals may also encourage filmmakers to apply to others abroad. It’s growing in Nigeria and so are the effects. Festivals don’t exactly function as an alternative form of distribution. They serve as conveyors. And presently, I don’t believe it can function as that yet, given where we are with things. But as they begin to grow in size and credibility, you may have sales agents/distributors from all over attending. I don’t think that’s far at all. And I suspect it’s already happening. I do indeed believe that it’s an excellent initiative to spur more creative undertakings and also to expand the amount of people coming to watch these films, which also enriches the palette of the uninitiated and those who already enjoy the alternative form. The more people we are able to convert, the better it is for all sorts of flourishes to occur with evidence to back our claims and guarantee numbers. I believe in exploring all distribution options: VOD, OTT, theatrical releases, etc. As filmmakers you want people to see your films, but you also want to make money to make more films and gain the trust and confidence of existing and potential investors.

6. What’s currently keeping you up? Any movies, TV shows, podcasts and/or books that you can recommend?

I re-read Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray” recently and it really is timeless. Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” is also very good. I was talking to a friend over the weekend and we plan to revisit some of the blockbuster and Sci-Fi films from the ‘90s. It should be fun. But at the moment, I’m looking at films from the Czech New Wave. Ivan Passer’s Intimate Lighting sticks out. I really enjoyed it.

The Annual Film Mischief is a hybrid festival celebrating quality low-budget Nollywood films from March 17-20. More interviews with other filmmakers and creatives in the industry and film essays will be published during this period. Register for The Annual Film Mischief here.

Join the conversation on Twitter: #TAFM22

1 Comment