Heist movies come in all shapes and sizes. For some reason, there’s something about seeing a team of highly skilled people steal large sums of money, priceless artifacts, or some other MacGuffin that gets us excited. Sometimes, the heist happens offscreen, and we are only privy to the events surrounding it, like in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. Sometimes, the heist is motivated by a desire for revenge and features a long line of A-listers and famous character actors looking cool and having a good time; if you immediately thought of Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven (2001), then you know your movies. Sometimes, the heist film is blended with another popular subgenre, much to the joy of audiences, like in 2015’s Ant-Man. And sometimes, like Charlie and the Boys, it has no idea what it wants to be or say.

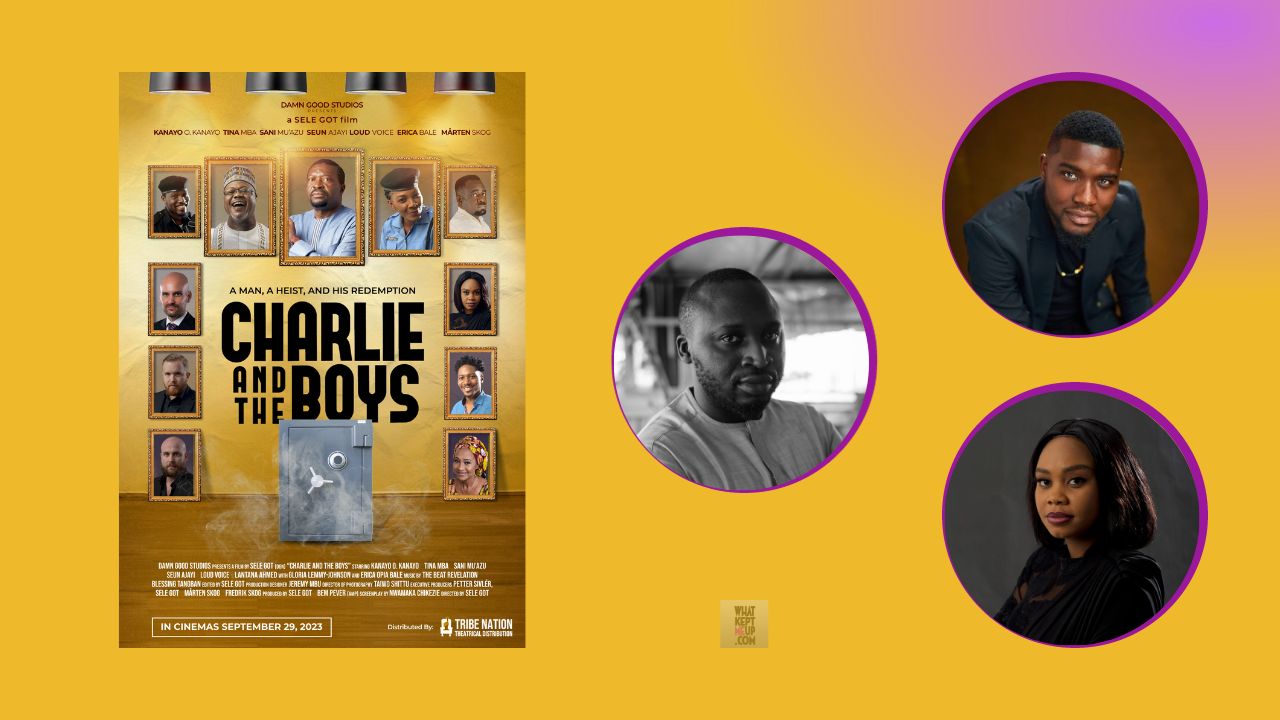

After a heist gone awry, Charles Omokwe, or Charlie (Kanayo O. Kanayo), is arrested and sentenced to 7 years in prison. He is released after 13 months, courtesy of a gubernatorial pardon. The story then follows him post-jail as he plots to get revenge on a client who double-crossed him, all while staying ahead of the law. He also has to win his way back into his wife’s heart and foot the bill for his daughter’s wedding.

The first thing one notices about Charlie and the Boys is that even though the film is marketed as such, it is definitely not a thriller. It is also a heist movie in the same way that Christopher Nolan’s Tenet is a comedy: barely. Yes, a precious artifact is stolen, and yes, that same artifact is stolen again, but there is very little evidence to convict the film of belonging to the subgenre it claims it does. Gone are the elaborate plans, the impressive schemes, and the dynamic sequences. Gone are the twists and turns. There is no instance of nail-biting suspense. The film simply trudges forward, forgetting to make us invested in any part of the plot, characters, or themes. There is a police officer, Philomena Fashood (Tina Mba), who is Charlie’s self-proclaimed nemesis because she has been trying to catch him red-handed for the better part of her career. However, her presence in the story, rather than leading to any interesting cat-and-mouse chase, feels like an afterthought. There is no real conflict here. No two characters have any compelling chemistry or drama.

The story leans more towards comedy than anything. And even in that area, it plays less like a feature narrative film and more like a comedy sketch that overstays its welcome, carrying on long after the punchline has been delivered. More effort was put in by the screenwriters and directors to make the audience laugh than was directed towards making the film suspenseful or thrilling. I repeat, the last thing this film is is a thriller.

Perhaps the biggest blunder of Charlie and the Boys is that the film contains no close-up shots. Not one. An odd choice indeed. It is not unheard of for films to make use of no close-ups, especially for projects that are filmed in one take, such as Birdman (2014) or Victoria (2015). And in the indie road-trip film, Stranger than Paradise (1984), the director, Jim Jarmusch, favors wide and medium shots, eschewing close-ups as much as possible. The saying that “comedy lives in the wide shot” is popular for a reason. Wide shots highlight instances of physical comedy as well as visual gags and misdirection, which might be hard to do when the camera is all up in a character’s face. However, there has to be some variety in the cinematography and editing, or else the story loses its momentum.

There are no insert shots of objects either. The camera seems almost hesitant to get into the nitty-gritty of the world of the film. I usually say that works of cinema exist on two levels: the viscera (the emotional or philosophical underpinning of the story) and the artifice (the exterior elements such as cinematography, costume design, production design, etc., which are used, like signposts, to hint at the viscera). This might be the first film I’ve seen in a long while that exists almost entirely as a sequence of surfaces.

Weirdly enough, I seemed to enjoy the film, especially past the midpoint when I accepted it on its own terms. It has an offbeat energy to it. The minimalism (which is less a conscious choice and more due to the constraints of the low budget) strangely held my interest. I thought it felt like a breath of fresh air in such a maximalism-heavy industry. However, if a film should be as unique as a fingerprint and bad blockbusters suffer because of too many fingerprints (due to meddling from the studio or whatnot), Charlie and the Boys is a smudge of ink where that fingerprint should be—a tonal mess.

Charlie and the Boys premiered in cinemas on September 29.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or join the conversation on Twitter.

Sign up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows with Google Calendar.

Side Musings

- I really wanted to like it, but the film is more negative space than actual substance. As this was a feature debut, I look forward to the next project from the director and screenwriters.

- Tina Mba appears like she’s overacting, but that’s not her fault. The other actors don’t seem to know what kind of film they’re in, so no one is on her wavelength.

- Close-up shots are one filmmaking technique used to help audiences relate to a character, motivation and all; however, because they aren’t used here, the audience is not easily compelled by Charlie’s quest for revenge.

- Come for the thrills, stay for the humor(?), be confused by the drama, feel cheated by the marketing.