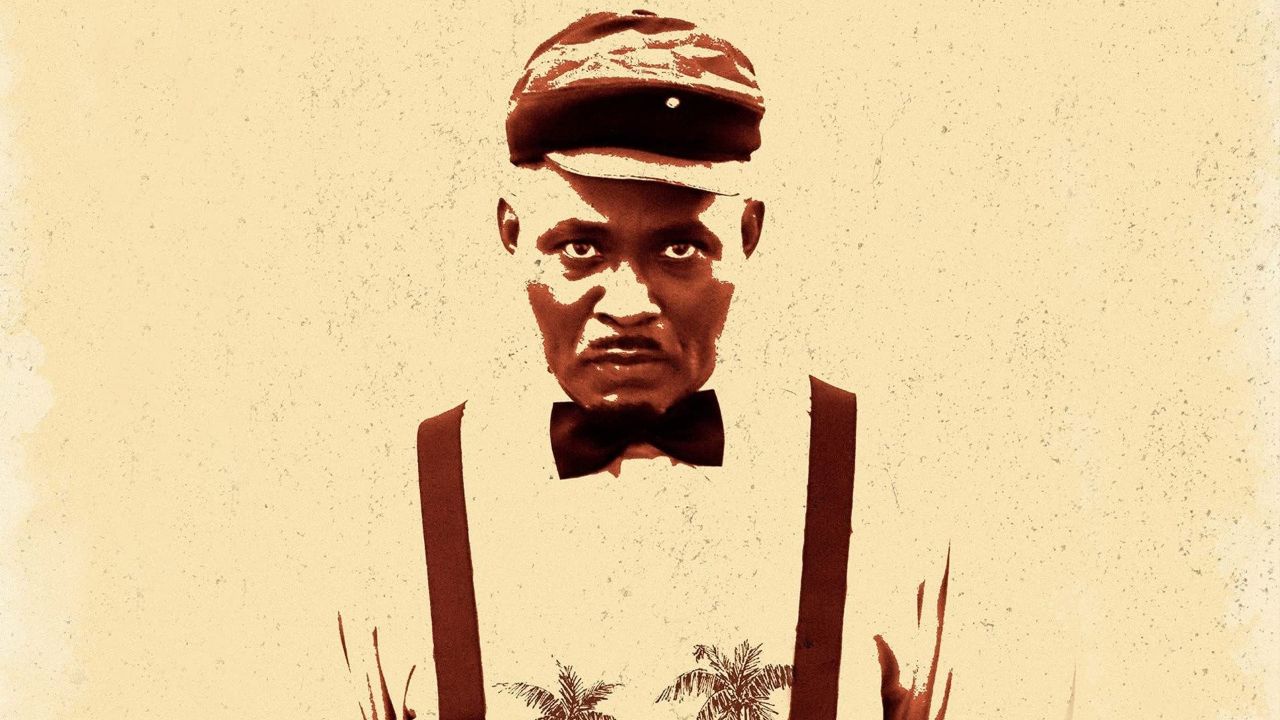

Oloture, premiering on Netflix in 2020, ends on a despondent note. A bus crosses the Seme border and slowly but surely recedes into the horizon, taking its helpless female occupants into what likely will be a difficult if not fatal future. They presumably are being trafficked to Europe where, to buy back their freedom, they must negotiate a bleak black market of transactional sex. Played by Sharon Ooja, one of the women is the eponymous Oloture, a fresh-faced undercover journalist who becomes a victim herself while investigating the inhuman world of human trafficking. A raw, keen-eyed study of human trafficking and its political affiliations, Oloture feels real because it’s premised on something real: a 2014 investigative report in The Premium Times not only contributed to its verbiage—high-ranking sex workers are called forza speciale—but also supplied some of its plot points.

An equally significant detail was the unlikely alliance between Kenneth Gyang, the film’s director, and EbonyLife Films, the studio behind its production. Up until then Gyang’s films, with their high style and modest commercial success, had seen him classed as an ‘art director,’ a label that grated on him because he believed it belied the breadth of his talent. Meanwhile, EbonyLife had traded in populist comedies, like The Wedding Party and Chief Daddy films. Teaming up, the director and studio scratched each other’s backs: Gyang was introduced to a mainstream audience and showed he can flourish in more than one cinematic register, while EbonyLife got the artistic cachet that had previously eluded it.

The film’s cliffhanger intimated a sequel would come, and five years later it’s here: a three-episode series, Oloture: The Journey, debuts on Netflix on June 28. Ooja returns alongside most of the original cast, including Omoni Oboli as a cold-blooded madam, Beverly Osu as one of several damsels in distress, and Ikechukwu Onunaku as a cruel pimp. The trailer makes clear that Gyang and EbonyLife continue their inquiry into the sleazy world of sex trafficking, this time seeking to convey a convincing vision of hopeless captivity. The trailer also suggests that, unlike the movie which is emplotted in Lagos’s underbelly, large swathes of the series take place in Niger; a desert figures prominently too. Perhaps the choices of scenery pay tribute to reports that indict the West African country as a major trafficking route, and that reveal sub-Saharan African deserts as a recurring, sand-clogged mise en scéne in the seedy trade.

Gyang doesn’t want the series thought of as a sequel. “I want it thought of as a complete work by itself,” he tells me, phoning in from his apartment in Lagos, a city he adopted as his home three years ago after a lifetime in Jos. He has just returned from New York, where his latest work This Is Lagos screened at the New York African Film Festival. Notably, this is where, ten years ago, his breakout low-budget film, Confusion Na Wa, was also screened. Of the city he has made his home, he says, “It has a certain energy.” But perhaps This Is Lagos offers a more eloquent insight into how Gyang sees the metropolis.

Like many big cities, Gyang’s Lagos is a thief of innocence. People enter it honest and unspoiled but quickly learn that it is more useful to be amoral. To survive the city, one must become the city in all its undulating deviousness: a lesson the film’s heroine, played by Laura Pepple, ultimately learns.

While Gyang’s female characters sometimes suffer cruel fates, as in Oloture, sometimes they are treated sympathetically, as when they are spared consequences insisted on by patriarchal morality. Where such moral codes condemn promiscuous women to a tragic fate, This Is Lagos’s female lead, a woman promiscuous not by choice but circumstance, discovers a liberating happiness in the end. It was a choice Gyang had to stand steadfastly by: the National Film and Video Censors Board, an institution peopled mostly by men, thought that an image of a promiscuous but ultimately triumphant woman would “send the wrong message.”

Though intimating us on how Gyang perceives Lagos, This Is Lagos is also a distillate of his experiences in the Jos of his childhood and teens. Jos, he says, has a “seedy” aspect, which in his mind as a child was epitomized by a hotel whose name he doesn’t recall. It’s the kind of hotel that people go to for a night of paid-for pleasure. It may be tempting to conclude that this reveals the director as one for whom sex work and moral rot are branches of the same poisoned tree, but his empathetic portraiture of sex workers in Oloture calls that thesis into question.

His debut feature Confusion Na Wa also pays tribute to Jos. Self-reflexive with a fragmented narrative, it stands out as postmodernist. Hacking at the theological notion that things happen for a divinely sanctioned reason, the black comedy wounds up as an articulate, oft-humorous denunciation of teleological meaning. So clearly set apart from the bunch when it was released in 2013, it was named the Best Film that year at the African Movie Academy Awards.

Upon its release the film could scarcely be grounded in any Nigerian cinematic tradition, testifying to its novelty. Not even Gyang had a Nigerian frame of reference, but instead had been strongly influenced by Francophone cinema, with his induction starting with Scenarios from the Sahel (2001), an anthology of shorts featuring works by Idrissa Ouadraogo, Fanta Régina Nacro and Cheick Oumar Sissoko. “Those filmmakers showed me that within Africa it was possible to make films with great cinematic story and quality,” says Gyang. “The Nigerian industry has caught up in this area but this wasn’t the case over a decade ago.”

Gyang’s literary roots perhaps explain the verbal fluency, channeled through his characters, that mark his works. This is perhaps best typified by a scene in Confusion Na Wa that features a trenchant deconstruction of The Lion King. Gyang’s father, a teacher, owned a large book collection that would make an avid reader out of Gyang, especially of the African Writers Series. He fell in love particularly with the works of the Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o for their sociopolitical consciousness and visual intensity.

A middle child with two sisters, Gyang was born to a middle-class family in Barkin Ladi, Jos, and grew up for the most part in West of Mines, a government-reserved area that he remembers as lush in foliage. “It’s the kind of place where children are raised by the whole community,” he says. It was in collusion with some of those children that young Gyang practiced shadow cinema, using improvised props like sticks and cardboard cutouts. A member of the COCIN church, he also partook in church dramas.

For Gyang there was no road-to-Damascus epiphany that made him realize he was going to spend his life making films, or that impelled him to enroll at the National Film Institute in Jos. Rather his interest was the unconscious culmination of films he had watched and books he had read and folklore he had heard from his grandparents. This gestation period, during which he binged on several artistic mediums, is a time that Gyang regards with nostalgic fondness: “For me, the 1990s was the most ideal period.” For Gyang the era embodied all the good the country can be, a prelapsarian paradise which, sadly, was upended at the turn of the century. The aughts, with the ethno-religious conflicts in Jos, would for Gyang come to represent a cultural degeneracy. Not one to shy away from self-referencing, Gyang aerates his works with his biases, as in Mojisola (2023), about a young woman (Tomi Ojo) who discovers her connection with water spirits, which though set in the present has car models from Gyang’s pristine ‘90s.

Gyang’s breakthrough came when his short, Mummy Lagos—a homage to a close friend’s aunt—was selected for the 2006 Berlinale Talents Campus that was held in Berlin. It was Gyang’s first trip out of the country, and the film lab would land him the opportunity to direct Wetin Dey, a BBC-produced TV series themed around HIV and AIDs, running from 2007 to 2008.

It was in Berlin he first met the British writer Tom Rowlands-Rees. And with Gyang’s longtime friend the Nigerian cinematographer Yinka Edward (his aunt is the Mummy Lagos), the trio co-founded an indie production company, Cinema Kpatakpata. The company boasts of an impressive collection, including Confusion Na Wa but also: a feature about a 1996 scandal around the pharmaceutical company Pfizer (Blood and Henna), two TV shows (How I Made My First Million and The Team), and some documentaries (Hafsat, Serah, Street Art, and Life’s A Beach). However, Gyang thinks the company ought to be more prolific: “Cinema Kpatakpata needs to produce more. There are talents around us with stunning stories.”

One of those talents is the Nigerian writer and filmmaker Julius Morno, whose debut feature, Life More or Less, will be produced by Cinema Kpatakpata. Gyang is currently fundraising for a film developed at the Ouaga Film Lab and EAVE Producers Workshop. “I also have three projects with stars already attached that I’m developing,” he adds.

With the Oloture series, Gyang will likely drift closer towards the nucleus of mainstream cinema. If he was inexperienced working with a studio at the time the movie was made, surely he was more at ease in the making of the series; but that’s not to say there were no hang-ups. There was a language barrier: some of the actors don’t speak English and translators had to be relied on. And Gyang and his crew had to brave inhospitable conditions while filming in the desert, enduring both extreme heat and extreme cold.

What does the series tell us about Gyang’s headspace? Why has he directed it? Where does it fit in his corpus? “What I make as an artist should be seen through the lens of most of my works with Cinema Kpatakpata,” he says. “Outside of that circle, I work on projects I feel go in line with what I feel about certain characters and what stories I want to tell through them. The Oloture series, like some of my films, has an interesting woman in the center of the unraveling of a sex trafficking ring. Through her, we are introduced to some of the economic and social challenges that women go through in contemporary African societies. In telling this thorny story of women trafficking, we have also managed to make a thoroughly engaging show that audiences will enjoy.”

Oloture: The Journey premieres on Netflix on June 28.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.