BFI: Vincho Nchogu‘s debut feature One Woman One Bra is a sardonic examination of intersecting failures that ensnare vulnerable women in rural Africa: archaic patriarchal systems, predatory NGO culture, and the performative benevolence of white saviourism.

(Click to Follow the What Kept Me Up channel on WhatsApp)

Shot in Nkosesia, Kenya with a runtime of 79 minutes, this Kenya-Nigeria coproduction anchors its socio-political critique on the story of Star Lepeko (Sarah Karei), a middlewoman who ferries goods between her rural Maasai community of Sayit and the township, only to discover that her entire existence rests on the most precarious of foundations: she has no documented claim to either her land or her identity.

The film opens with the unhurried rhythms of pastoral life—thrift sales, livestock rearing, the daily commute on a motorbike—establishing the world Star inhabits before dismantling it piece by piece. When she stumbles upon William Whitman’s “World Book of Nomads” and finds her childhood photograph gracing its cover, the discovery feels like a benediction, a visual confirmation of her place in the world. She frames the cover.

But this moment of recognition is a cruel prologue to erasure: during a land allocation exercise, Star’s name is conspicuously absent. The village chief offers hollow reassurances even as an evacuation order looms. The terms of her survival are made brutally clear: produce evidence of parentage, get married, or raise money to make an outright purchase of what should already be hers.

Star, unmarried and orphaned, possesses none of these lifelines. The chief’s taunting reminder of her refusal to wed one of the village elders underscores the transactional nature of women’s security in Sayit: worth is tethered to marital status or male lineage, and independence is tantamount to treason. What begins as a mission to secure her patrimony pivots into something far more existential: a search for the parents she cannot remember, for proof that she belongs anywhere at all.

A misunderstood conversation at a soirée leads to the launch of a bra donation campaign for the women of Sayit. Star and the women create a video, expecting cash donations. Instead, they receive bras. The video brings not salvation but catastrophe: one of the young women featured in the footage is stalked and harassed. Star finds herself ostracised by the very community she sought to uplift.

Nchogu constructs a narrative that interrogates multiple systems of oppression. One Woman One Bra asks uncomfortable questions about archaic customs that deny women property rights and render them chattels passed from father to husband. But it also turns its gaze outward, implicating the exploitative photojournalists and carnivorous NGOs who extract images and stories from vulnerable communities, repackaging suffering into fundraising collateral while delivering solutions no one asked for. The bra campaign is a masterstroke of satirical fury, a symbol of how aid can become another form of colonisation, where the giver’s imagination supplants the recipient’s reality.

Sarah Karei anchors the film with a performance of quiet ferocity. Her face registers every calculation, every hesitation, every flicker of hope extinguished by systemic cruelty. Cinematographer Muhammad Atta Ahmed (Freedom Way) captures her pensiveness in lingering close-ups: Star sliding to the floor in agony, grimacing as she weighs impossible choices. Josh Olaolu‘s production, supplemented by Nuur Abdulkadir’s design, renders Sayit as a believable space where lives and livelihoods teeter on the edge of chaos.

The film does stumble in its opening stretch, spending perhaps too much time on establishment shots that, while atmospheric, delay the narrative’s propulsion. Nchogu spends considerable time setting the tone of Sayit’s milieu. But once the stakes crystallise, the pacing accelerates with quick cuts that mirror Star’s mounting urgency.

The stylistic choice to filter the story entirely through Star’s perspective creates tunnel vision by design. Supporting characters remain underdeveloped, their backstories sketched rather than excavated. But this narrowed lens serves a purpose: we experience the claustrophobia of Star’s isolation, the disorientation of navigating systems designed to erase her. By zooming in on one woman’s plight, Nchogu deploys her story as a metaphor for systemic violence. The scene in which community members storm Star’s home and cart away her belongings is devastating in its brevity, a reminder of how quickly the vulnerable can be dispossessed when communal structures turn predatory.

The film’s interrogation of communalism cuts deep. It does not romanticise collective life; instead, it exposes how community can become vulturous, how solidarity can dissolve in the face of scarcity and scapegoating. Star’s ostracisation is not the work of strangers but of her peers, women who might have stood beside her but choose instead to cast her out.

For the orphaned Star there is no respite, no reprieve as she struggles to hold on to what little she deems precious. The story posits that perhaps the essence of it all is in the fight itself, that meaning is forged not in victory but in the act of unraveling, of refusing to disappear quietly.

One Woman One Bra is a feature that is both an intimate character study and a blistering systemic indictment. In Nchogu’s unflinching vision, Star’s battle is both deeply personal and devastatingly universal; a portrait of a woman caught between systems designed to erase her, searching for a foothold in a world that offers none. In her quest for selfhood, we witness not just one woman’s struggle, but a mirror held up to societies where autonomy is a luxury and survival could translate to the surrender of dignity. It is a film that lingers, uncomfortable and necessary, long after the credits roll.

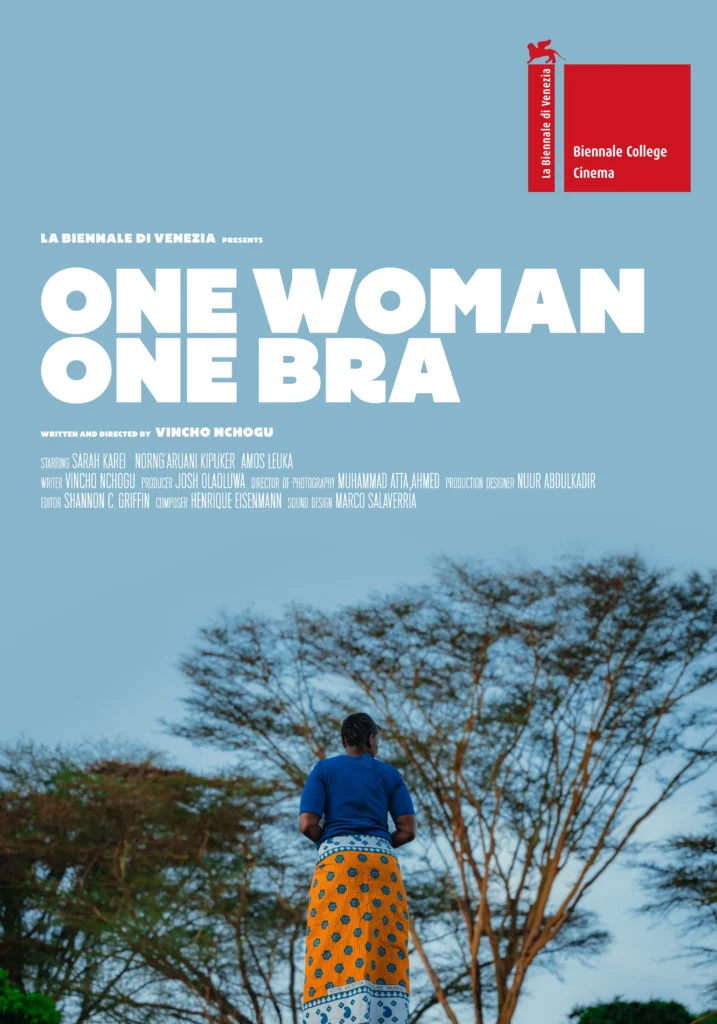

One Woman One Bra screened at this year’s BFI London Film Festival (which held from October 8-19) for its UK premiere. This builds on its world debut at the Venice Film Festival in August, an outcome of its selection for the latter’s Biennale College Cinema programme in 2024. It won the Sutherland Award at the BFI Film Festival.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Side Musings

- It was quite interesting seeing the people of Sayit use smartphones (with some of the ladies even having Instagram accounts), while lacking bras.

- In one scene where she’s harangued by her neighbours, Star runs out of the house and jumps into the driver’s seat of a truck. The truck develops a fault in the middle of nowhere, and Star decides to spend the night in it. For an orphaned woman with a target on her back, that felt incongruous.

- Star’s final move in the closing montage was an ultimate act of defiance after the pyrrhic victory, considering that the other villagers had previously raided her apartment and taken all she owned.

- NGOs and white men living in African conservancies are never beating the allegations.

1 Comment