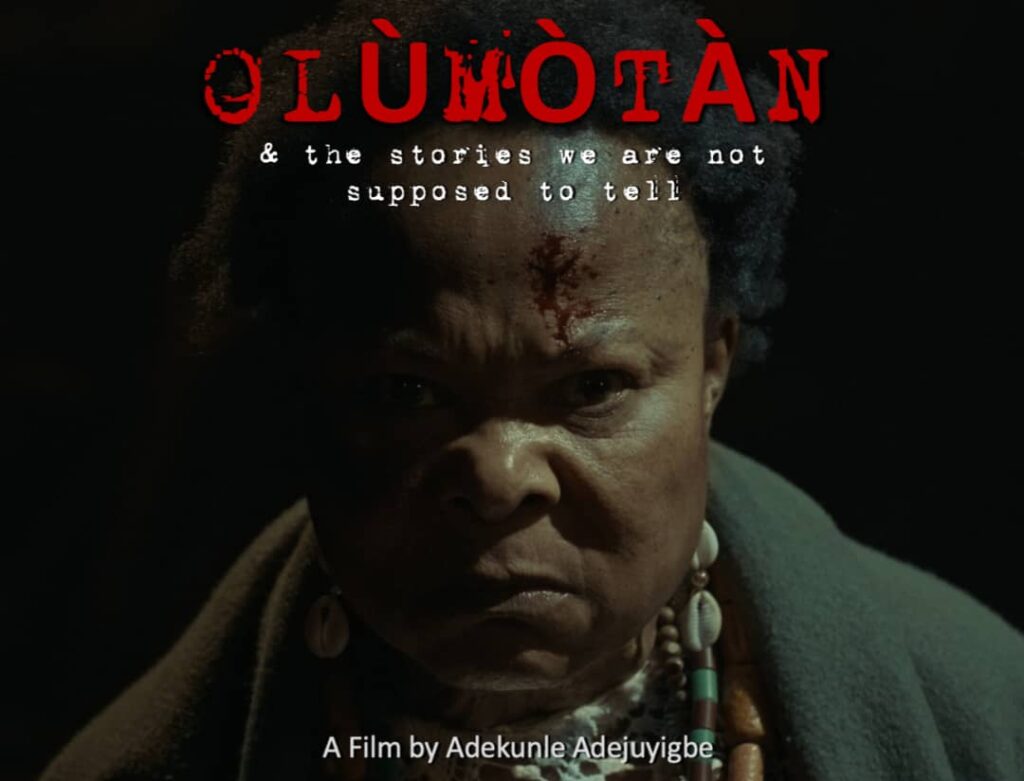

Olumotan: The Trial of the Storyteller begins with a certain kind of awareness. First, there seems to be a breaking of the fourth wall by the storyteller played by Sola Sobowale, and then a multicultural audience is revealed within the film, witnessing the trial of this storyteller. This awareness of both us as the audience outside the film and the audience within the film seems to guide this anthology of four stories that cover themes like justice, happiness, religion and identity. But there seems to be more concern for us outside than the audience in front of The Storyteller.

The Storyteller weaves these four stories, all directed by Adekunle Adejuyigbe (The Delivery Boy), of varying quality and lengths, to form a tapestry that is supposed to reveal something to and about both audiences witnessing them. The first one titled “The Last Condom” is set a day before the lockdown in 2020 and follows a group of four people— a street urchin, a spoilt rich man, a police officer returning from London, and a presumed sex worker—who come to a shop in search of condoms only to find that there’s just one left. They get into escalating confrontations with themselves and the shop owner, played with an element of offensive caricature by Blossom Chukwujekwu (The Trade), till they reach a violent end.

A funny, chaotic tale that manages to capture the brain fog of 2020, “The Last Condom” distills the unusual interpersonal tension, desperation and violence that existed in that period and puts that energy expertly in the single room it is set in. Often deeply visceral and shot with gusto, it features performances that range from excellent— Tomiwa Tegbe melts into the street urchin, to average— Bikiya Graham-Douglas is alright as the policewoman just returned from London, and to awful— Ibrahim Jammal is unrecognizably bad as the spoilt rich man. The reveals in the story are often clumsy, but it doesn’t derail its momentum. In the end, the policewoman is transformed into a violent horror that makes you wonder if COVID transformed us into worse versions or just revealed a violent core that exists in humanity.

The second story, titled “Life Is Good,” starts with a dual dosage of bad acting from Mike Afolarin as OJ and Shine Rosman as his perfectly beautiful wife, Feturi. It chronicles his almost perfect life as a former reality television star, turned former musician, turned financial analyst. The only catch is that he must perform some unknown ritual in the toilet with a book titled “Ancient Secrets to Mystical Power”—couldn’t have found a more on-the-nose name—that he carries everywhere to keep this life he’s living.

The story trudges on to a twist that leaves you unmoved and somehow bogs down all the performances in this section—luckily, Afolarin redeems himself in the second half. This film clumsily asks what price we are willing to pay for happiness, and one would care more for whatever interrogation it presented if the story was not focused on whatever mystery lay inside the book. A drop in quality from the first story, it still sometimes works, presenting interesting parallels between his life of wealth and poverty, but deploying tropes steeped in exaggerated physical ugliness as indicators of low-class status.

The next story is a step up and also the shortest of the bunch. Set in a pastor’s wife’s office, “White Dogs” follows Martha Ehinome as Bisola, who comes to meet this pastor’s wife (played with authoritative verve by Bola Stephen-Atitebi) with complaints of nightmares where black dogs kill white dogs despite numerous attempts at deliverance. Filmed solely in black and white, the sinister energy drips from the screen, which gives an interesting contrast to the supposed hope this meeting is supposed to give.

It takes an age-old Christian warning about sex and spirituality and places it in a somewhat predictable but effective position in the film. The singular location keeps the section tight but not boring as it constantly plays with light and darkness: evident in the way the pastor’s wife’s hat frames her face, blocking and revealing as her rhetoric enters questionable territory. This story is particularly interesting as it leans heavily into Christianity’s dark centre in Nigeria without any heavy-handedness and still maintaining an air of mystery.

The final story in this sprawling film of two hours and thirty minutes is titled “The Corn Roasters”. It starts with a woman (Taiwo Ola) trying to escape a group of violent killers before switching to her past, where her father (played by William Benson) constantly reminds her of her ancestors and how her identity is tied to them despite her teenage resistance. It continues to move back and forth with sly editing and match cuts: present her trying to evade the killers and past her learning about her family tree, before culminating in a spiritual battle triggered by her remembering who she is. The best word to describe this last story is `alright.` It is competent but a bit heavy-handed with its message and stalls the present to fill in the gaps in the past, but its presentation of power within identity serves a repeated message in a fresh way.

Now, after treating these stories as individual pieces, the next question is, how do they serve the overarching narrative of the storyteller who is standing trial and telling them? Before each story is presented, Sola goes on some sort of monologue before presenting a question that leads into each section. At the climax, the stories incite the audience witnessing her trial till the point of being stoned, but we never really get a convincing sense of her crimes and the motivation behind this trial.

A generous reading is that it is the outside viewers that she first spoke to that are the true audience at her trial and our reactions are the many ways this film can be interpreted—but sadly, that seems like reaching. Olumotan makes it seem like these stories are revealing a truth that these people do not want to contend with, but all we get are bursts of anger and murmuring after each story and never some sort of containment of the main narrative that seems to drive the stories. After each story, newspaper headlines are shown with real-life scenarios that resemble each of the stories and that contributes to the film’s obsession with how it is perceived outside itself.

Olumotan is bold and daring with its stories, but careless with the audience of these same stories, which makes you wonder: who came first, the stories or the storyteller?

Olumotan was the closing night film at the 12th edition of the NollywoodWeek (NOW) Film Festival 2025.

Become a patron: To support our in-depth and critical coverage—become a Patron today!

Join the conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Track Upcoming Films: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- Mike Afolarin being a singer in yet another film. Welcome back, King Kator from A Lagos Love Story!

- When OJ looked at the screen filled with red and green numbers while the music was tense in the background, I felt nothing because I had no idea what he was even looking for.

- I wonder what service at the church in the “White Dogs” section feels like. I know they have a packed congregation.