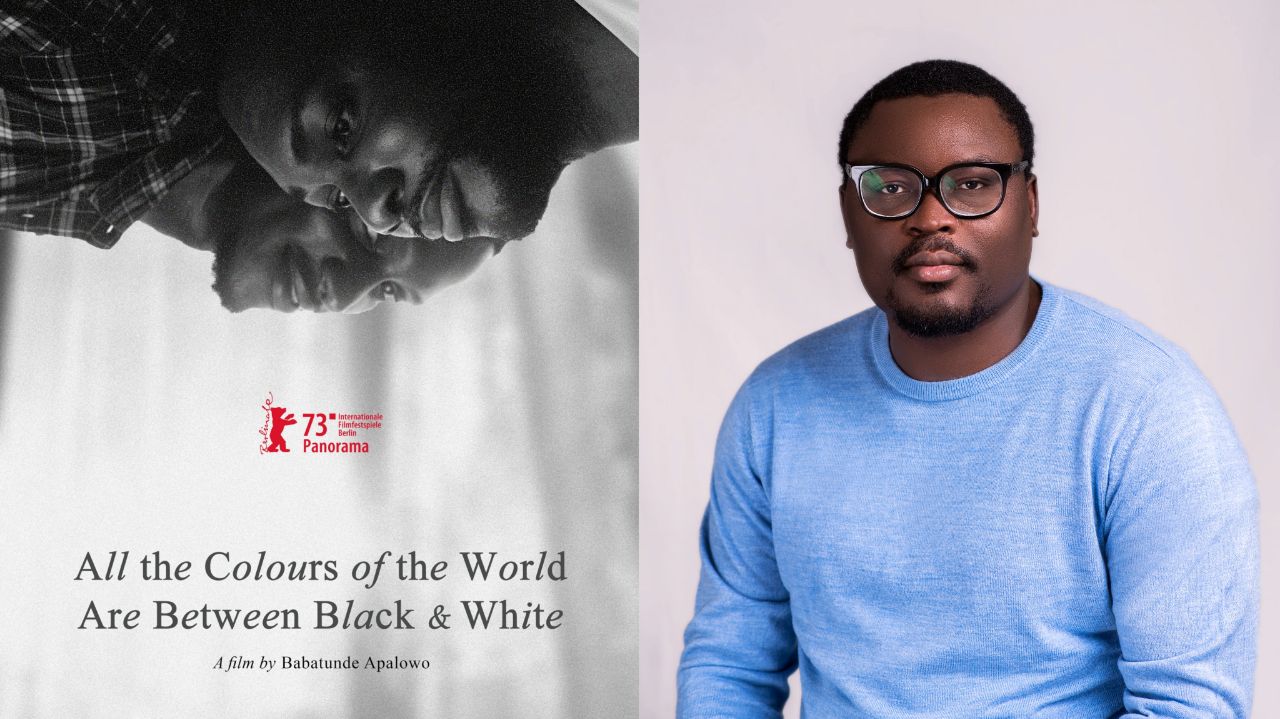

EXCLUSIVE: What makes the world premiere of All the Colours of the World Are Between Black and White special for Babatunde Apalowo is that the film is his first feature film. Premiering at the Berlin International Film Festival, the film joins the Esiri brothers’ Eyimofe, which was the first Nigerian film to premiere at the prestigious festival, with both films placing their restrained cinematic lens on overlooked aspects of the Nigerian human condition.

Produced by Damilola Orimogunje, All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White follows the journey of Bambino (Tope Tedela) and Bawa (Riyo David), who meet in Lagos and start to develop feelings for one another. The two men find it difficult to express these feelings, however, because they are in a society that considers homosexuality a taboo.

Screening in the Panorama Section of the Berlinale and going home with the Teddy Award, this feat adds Apalowo to a growing list of Nigerian films to screen at prestigious international festivals. Already in 2023, C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s black and white folktale Mami Wata screened at Sundance and won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Cinematography.

Apalowo, who has written for films such as Catch.er and Jolly Roger, doubles as the writer of All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White. He has also made other festival appearances through his short films, such as Crack and A Place of Happiness, which screened at the African Film Festival in Texas in 2017.

In this exclusive interview with Fancy Goodman, Apalowo discusses his experience being an independent Nigerian filmmaker, the challenges he faced treating a controversial subject in his film, and the current state of Nollywood.

‘Mami Wata’ Sundance Film Festival Reactions and Reviews

‘Mami Wata’ Sundance Film Festival Reactions and Reviews

Congratulations on the premiere of your first feature film at the Berlin International Film Festival. What was the process like for you, from the ideation stage till the festival stage?

The process was quite iterative, with changes occurring from the ideation stage up until the festival stage. Initially, it started as a story about a man’s love for his city, but evolved into a love story about two men who cannot be together due to the limitations of their environment. However, the story had to be further modified during production due to casting challenges and other factors.

Post-production presented its own set of challenges, particularly with regard to editing. We had to make tough choices about what to keep, what to cut, and how to pace the story to maintain its emotional resonance. Through it all, however, there was a core anchor that remained constant: the love story between the two men. This was the heart of the film, and we were determined to preserve it in spite of all the changes and challenges we faced. In the end, I am proud to have completed the film and to have premiered it at the Berlin International Film Festival.

The title of your film is quite unusual for its length, possibly one of the titles with the most words that Nigeria has produced. How did you come up with it, and is there a special reasoning behind it or other ways it could have gone?

All the colours of the world are literally between black and white. Take any colour and increase the brightness, it gets to a point where you will end up with white. Decrease the brightness and, of course, you get black. But it is a commentary on the idea that love and relationships are not limited to a binary concept of heterosexuality or homosexuality, but rather there is a wide range of diversity within these categories. There are complexities of love and relationships between people of the same gender or different genders. To be honest, it all depends on the nuances of their experiences.

It’s also a metaphor for the idea that love, like colours, exists on a spectrum, and that there are many shades in between the extremes of black and white, and that life and the world are not always clear-cut or simple. And finally, It is a commentary on Nigeria’s view of the LGBTQ+ community, and how it is often viewed in black and white terms, when in reality, there is a wide range of diversity within this community. I don’t think I could have come up with a better title for the film.

In your interview with the Berlinale press, you mentioned that the film was meant to be a love letter to Lagos, and that Lagos influenced the film. What are your thoughts on some critics’ arguments that too many Nollywood films are set in the city of Lagos?

Lagos is the pulsing heart of Nigeria, a city of contrasts and contradictions, where beauty and chaos collide in a kaleidoscope of colours and sounds. As a filmmaker, I was drawn to Lagos as a canvas on which I wanted to paint a love story, a tapestry woven from the threads of everyday life. In All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White, Lagos is more than just a backdrop; it is a living, breathing character: an actor in its own right.

It’s true that many Nollywood films are set in Lagos, but I believe that All The Colours offers a fresh perspective on this vibrant city. Through the lens of our camera, we capture the essence of Lagos: the frenetic energy of the streets, the pulsing rhythm of the music, the vibrant hues of the markets and the stunning sunsets over the Atlantic. We also reveal a side of Lagos that many have not seen before: the quiet moments of introspection, the delicate dance of two lovers navigating a society that does not accept their love.

My vision for All The Colours was to create a love letter to Lagos, a tribute to the city that has inspired and challenged me as a filmmaker. I hope that viewers will experience Lagos through our film as a place of beauty and complexity, where the human spirit thrives despite the odds. Lagos is a city that refuses to be ignored, and All The Colours is our humble attempt to pay homage to this dynamic metropolis and its people.

In 2020, Eyimofe was the first independent Nigerian film to screen at Berlinale. How would you say this influenced you as an independent filmmaker?

Eyimofe, in my own opinion, is one of the greatest films ever made. I’m so proud of it because it’s a Nigerian film. The showcasing of Eyimofe at Berlinale in 2020 marked a monumental moment for Nigerian cinema, and as an independent filmmaker, it had a profound impact on me. Witnessing a Nigerian film being celebrated on such a global stage was not only inspiring, but also eye-opening. It made me realize the endless possibilities and potential of Nigerian storytelling, and how it can captivate audiences far beyond our borders. The influence of Eyimofe on my own film, All The Colours, cannot be overstated. It inspired me to push the boundaries of what a Nigerian film can achieve and aspire towards.

You’re also a writer and editor. How would you say these other filmmaking skills have helped you as a director?

As a filmmaker, I believe that the essence of the art form is the story, and my skills as a writer and editor have helped me to refine that story at each stage of the process. Writing allows me to create a narrative that is uniquely mine, while editing gives me the tools to sculpt it into the most compelling version of itself. As a director, I am constantly aware of the power of these tools, and I use them to craft a story that is intentional, impactful, and beautiful. In the end, the art of filmmaking is really the art of storytelling, and I am grateful for the skills I have developed that help me to tell those stories with precision and grace.

As a filmmaker now on the audience’s radar, what kind of stories do you want to tell, and what should they expect from you?

I aspire to tell stories that are deeply personal and close to my heart. I want to explore a diverse range of themes, from the beauty and complexities of love to the mysteries of time and the inevitability of death. My interests are varied, and I hope to delve into different genres, from heartwarming romances to mind-bending science fiction. Overall, my goal is to create films that are authentic, thought-provoking, and emotionally resonant. For those who follow my work, they can expect stories that are both challenging and rewarding, with characters that are deeply human and stories that are rich in meaning.

Should we expect you to take risks like this in the future with controversial subjects like LGBTQ? Also, how were you encouraged to go ahead with production, given the nature of the subject in Nigeria?

Certainly. As a filmmaker, I am not averse to telling stories that challenge and provoke, and to exploring themes and issues that are often seen as taboo or controversial. I believe that cinema is a powerful medium for exploring these kinds of subjects, and for sparking conversations that can lead to meaningful social change.

In terms of how I was encouraged to go ahead with production, I was fortunate to work with a team of passionate and dedicated professionals who believed in the project and in the power of cinema. We faced many challenges along the way, including funding issues, casting difficulties, and potential censorship, but we persisted because we believed in the importance of telling this story.

Ultimately, I believe that as artists and storytellers, we have a responsibility to challenge the status quo, push boundaries, and shine a light on the marginalised and the voiceless. This is what I hope to do with my future work, and I look forward to taking on new challenges and exploring new frontiers as a filmmaker.

You mentioned in a statement to What Kept Me Up (WKMUp) that you hope the film will be seen by many Nigerians. How do you intend Nigerians see your film, keeping in mind that there is a high possibility that it gets banned or censored?

As a Nigerian filmmaker, it’s important to me that my work is seen by as many Nigerians as possible. I believe that All The Colours is a film that speaks to many of the experiences and challenges that some Nigerians face, and it is my hope that it can contribute to the cultural conversation in our country. While I am aware of the possibility that the film could be banned by the government, that is something that is outside of my control. Our goal is to create a work of art that is honest, authentic, and true to our and people’s experiences, and we believe that by doing so, we are making an important contribution to the Nigerian cultural landscape. Whatever happens, I am proud of the work that we have done, and I hope that it will be seen and appreciated by audiences in Nigeria and beyond.

Did the controversy of the film almost deter the team at any point from telling the story as it is?

The team was aware of the potential risks involved, but it never deterred us from telling the story we wanted to tell. In fact, it only strengthened our resolve to tell the story authentically and with integrity. We knew that the subject matter was controversial, we accepted that fact, but we also knew it was an important story that needed to be told.

As with any film production, there were challenges along the way, including difficulties with casting which was peculiar in this instance. Despite these challenges, the team remained committed to telling the story as it was meant to be told, and we are incredibly proud of the final product.

What are your influences? Which local/foreign films and filmmakers have shaped you?

I draw inspiration from a lot of different films and filmmakers. Locally, as I mentioned earlier, Eyimofe was a big influence, but I also look to other Nigerian filmmakers like Mike Omonua and Dami Orimogunje. From a global perspective, I find inspiration in the works of filmmakers like Wong Kar Wai, Celine Sciamma, and Terrence Malick. I am drawn to their ability to craft deeply emotional stories, often with a unique and captivating visual style. I also look to Asian cinema for influence, as their cultural values and cinematic aesthetic, while different, can be quite similar to Nigerian culture.

What is it like being an independent Nigerian filmmaker? What challenges have you faced so far? And what are the advantages?

Being an independent Nigerian filmmaker can be both challenging and rewarding. On the one hand, there are many obstacles that can make it difficult to produce films, such as limited funding, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of institutional support. On the other hand, being an independent filmmaker also allows for greater creative freedom and the ability to tell stories that might not be possible within the mainstream industry. It’s worth noting that while Nollywood is often associated with independent filmmaking, there are also large studios and production companies within the industry. However, many independent filmmakers have found success within the industry and have helped to shape the unique style and approach of Nigerian cinema.

Some of the specific challenges I’ve faced include finding funding for my projects, which can be a difficult and time-consuming process, as well as dealing with the logistical and bureaucratic challenges of filming in Nigeria. Additionally, there is a limited market for independent cinema in Nigeria, which can make it difficult to find distribution and reach audiences.

Despite these challenges, there are also many advantages to being an independent filmmaker. For example, I have more control over the creative process and the ability to tell the stories that I’m most passionate about. Additionally, there is a growing audience for independent cinema in Nigeria, and I believe that the future is bright for filmmakers who are willing to take risks and tell compelling stories.

Lately, Nollywood has had an increase in the number of films put out by independent filmmakers. What role do independent filmmakers have to play in the industry?

In recent years, Nigerian independent filmmakers have played a critical role in the development of the country’s film industry. They have introduced fresh perspectives, new styles, and innovative techniques that have expanded the boundaries of what Nigerian cinema can be.

The success of independent filmmakers such as the Surreal16 arthouse directors, Ebuka Njoku and Dami Orimogunje has demonstrated that there is an audience in Nigeria and beyond for films that tell stories in unconventional ways and tackle challenging themes. These filmmakers have been able to create work that is authentic, thought-provoking, and deeply personal, which has helped to diversify the types of stories being told in Nigerian cinema.

Overall, independent filmmakers have been instrumental in pushing the boundaries of Nigerian cinema, encouraging experimentation and innovation, and exploring new possibilities for storytelling. They are contributing to the growth of the industry, documenting the experiences of Nigerians and inspiring the next generation of Nigerian filmmakers to think outside the box and tell their stories in new and exciting ways.

If you were to list the two things that Nollywood needs the most, what would they be?

Improved infrastructure and funding. Nigeria’s film industry still lacks adequate infrastructure and funding to support the development and growth of the industry. Many filmmakers struggle to secure funding for their projects, and there are few resources available to support the distribution and marketing of independent films. Improving the infrastructure and funding for Nollywood would go a long way toward supporting the growth and development of the industry.

More emphasis on quality: While Nollywood has made significant strides in recent years, there is still a need for more emphasis on quality in all aspects of film production, including scriptwriting, cinematography, editing, and acting. By prioritising quality, Nollywood can continue to improve the overall reputation of the industry and attract a wider audience, both locally and internationally.

Since streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime launched in Nigeria, Nollywood has been churning out a lot more films. What would you say about the quality of films in the last five years?

While the increased interest has led to more opportunities for filmmakers and actors, the quality of the films has been mixed. There have been some standout films that have received critical acclaim both in Nigeria and internationally, such as For Maria, Juju Stories, The Milkmaid and Eyimofe. These films have demonstrated that Nigerian filmmakers are capable of producing works of art that can compete with the best in the world.

However, there have also been many films that are poorly written, acted, and produced, with little attention paid to the craft of filmmaking. Some of these films have been widely criticised for perpetuating negative stereotypes about Nigerians, and for being poorly researched and executed. These films cast a bad image for the Nigerian film industry and rubbish the attempts by other filmmakers striving for excellence.

Overall, while the increase in production has led to more opportunities for Nigerian filmmakers, it’s important that the focus remains on quality rather than quantity. There is still much work to be done to improve the standard of filmmaking in Nollywood, and to ensure that Nigerian stories are told in a way that is both authentic and artistically compelling.

All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White had its world premiere at the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

5 Comments