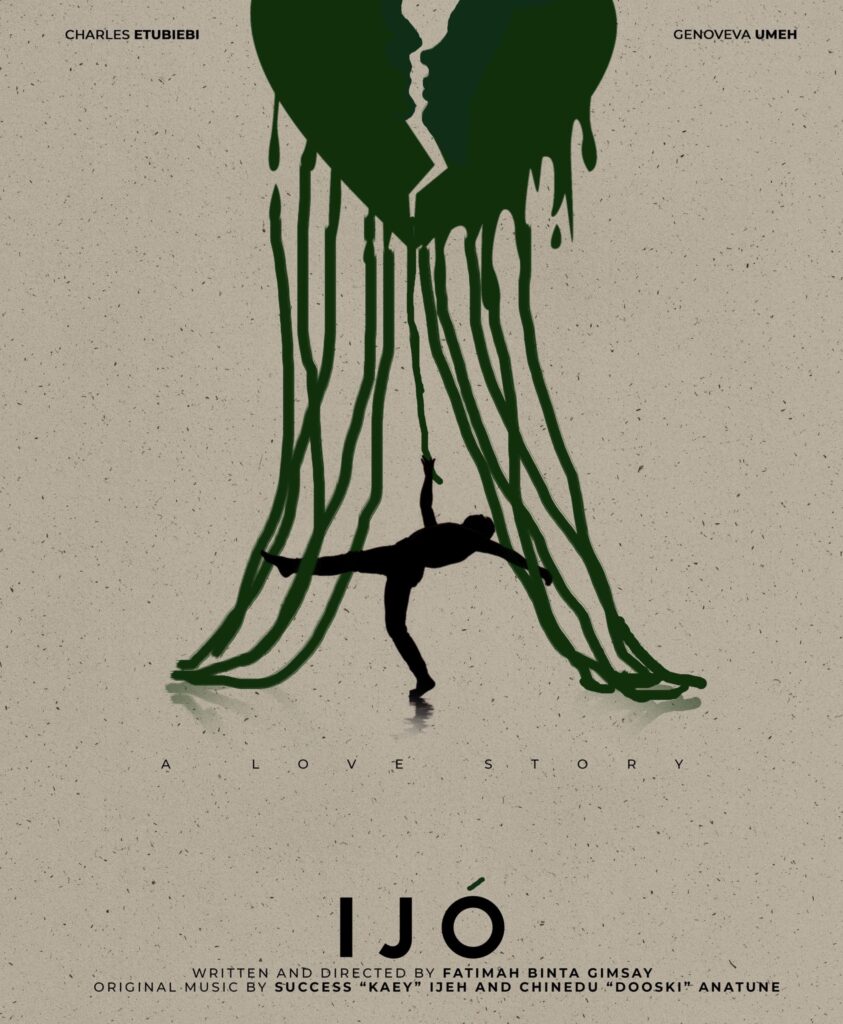

Dance has been employed in various ways throughout film history. In Footloose (1984), it’s a symbol of teenage rebellion and expression. More recently, Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit (2019) ends with the main characters dancing in front of their home celebrating their freedom as the Third Reich falls to pieces around them. And in The Wedding Party (2016), a dance montage is used among other things as visual shorthand to show the audience how much the characters have changed. Fatimah Binta Gimsay, in her short film, Ijo, makes dance the final straw that shatters the wobbly foundation of a marriage.

Every film is a kind of dance. The first time I heard that statement, I had only a vague idea of what it meant. But as time went on, I was reminded of the relationship between dance and film and the similarities they share as mediums of expression. Both of them appeal primarily to the eyes through movement. Dance can be used to express emotions clearly, without the need for words. Film also relies heavily on movement in form of the blocking of actors and the staging of the camera; like dance, it depends on outer physical expression to convey inner feelings and emotions, especially in its early days, during the era of the silent movie.

Related:

‘Hex’ Review: Clarence Peter’s Horror Short Film is Gritty But Without Fright

‘Hex’ Review: Clarence Peter’s Horror Short Film is Gritty But Without Fright

Debo (Charles Etubiebi) and Molara (Genoveva Umeh) have been married for three years and when we meet them, it is their third-year anniversary. Molara does not seem as delighted about it as Debo, who has a dinner planned for later that night. Molara, on the other hand, wants to go to her dance class as usual and see a play with her colleagues after. “It’s just an anniversary, it’s not that deep,” she says to Debo who looks increasingly distraught by the minute. “Are we fighting,” he asks. It is clear that there is something fundamentally wrong; there is big trouble in their little paradise.

For Molara, dance is a kind of escape from her marriage, from the clutches of Debo who is admittedly “painfully obsessed” with her. She doesn’t love him anymore; he’s not artsy and creative like Koyemi who understands her. Molara cheated on Debo some months before and he forgave her instantly. She is now adrift, unable to run into Koyemi’s arms (which would have happened had Debo reacted violently). “Who asked you to forgive me?” she says to him bitterly, “you forgave me without my consent.” The audience is put in Molara’s headspace with those words. It is clear why she is always going dancing, why she stays out for as long as she can: being with him is killing her. Like most of us, Molara is turning away from forgiveness, because she isn’t really sorry. Debo kneels down before her in tears, saying “I will surrender my life. Please don’t leave me.” I imagine that line hit her like a sack of bricks. If for some reason, she was still considering staying with him, once Debo begins to beg, that option is definitely out the door.

Related:

Short Film: ‘Hers, Mine, Ours’ Review

Short Film: ‘Hers, Mine, Ours’ Review

This scene goes on for about ten minutes and is the major part of the short film. It’s wonderful that Fatimah Gimsay, as writer and director, is able to not only hold the attention of the audience but keep us intrigued throughout this time. It never feels repetitive either, like we’re going in circles aimlessly. With every new line, a little more of each character’s psyche is exposed, with each tone of voice, their motivation becomes clearer. The dialogue is fresh and the actors truly sell us on the devastation their characters are feeling, especially Etubiebi who seems to be able to do more acting with his eyes than a lot of Nollywood performers can with their entire bodies.

The film is a little rough at the edges though. The scene where they’re arguing could have been made more exciting by making really good use of the space. Spielberg once said, “a character should never walk in. They should storm in. They should skulk in. They should tremble in. Create visual pictures.” In Ijo, the characters do not interact enough with the setting, props and each other in a way that reveals their inner states, which informs the audience about their peculiar traits.

The film ends with Debo dancing in a studio in front of a full-length mirror as a voice-over informs the audience that Molara is dead; she was involved in a car accident on her way to meet Koye. Is Debo’s dance supposed to be a coping mechanism for his loss, a way to remember Molara? Or is it a way of showing how he’s learned to let go and be artsy like Molara was telling him to be? Either way, his decision is still centered around his ex-wife— the one he was “painfully obsessed” with, the one who shouted in his face that she didn’t love him and wished she’d met his friend first— and it is an odd choice. If we had seen Molara dancing at the beginning, it’d have informed us more about how much dancing means to her, how she’s using it as an escape from her husband and how much internal conflict she has to bear. Debo’s dance at the end would have also been evocative; it’d have been a way to bookend the film by showing the other character going through similar inner turmoil. It honestly seems like a missed opportunity.

Like I said earlier, dance is the perfect, most basic medium for expressing emotions clearly without the need for words. Film is a close second. Both of them together are essentially a supernova.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows with Google calendar.

Side Musings

- The soft, warm lighting contrasts well with the “Scenes from a Marriage” type argument.

- Charles Etubiebi is especially good in Jude Idada’s short film, Queen of the Night.

- I’ve seen Ijo about four times now and it has only gotten better with each watch. It’s the writing that really gets you. It’s available on YouTube right now. Kudos to Fatimah Gimsay. We can only expect better and better.

Ijo is available on YouTube.

4 Comments