According to SBM, there have been 391 mob killings in Nigeria since 2019. In May 2022, a young lady, Deborah Yakubu, was stoned to death and then immolated in Northern Nigeria. And as recently as 2023, Sima Essien, an undergraduate of the University of Nsukka, almost lost his life to a mob for a falsely accused crime. Two suspects were arrested in May after Deborah Yakubu’s murder in Sokoto, but they have still not been brought to trial, and the police have said the main culprits are still at large. A police van drove by while Sima Essien was being mobbed, but they did nothing to rescue him. Defenders of jungle justice say that the police rarely carry out their duties when they arrest criminals, and so the people should be allowed to mete out justice; yet in both cases of Deborah Yakubu and Sima Essien, the police have clearly failed the victims.

‘Shanty Town’ Review: Scalar But Lively Chidi Mokeme Saves The Day in Gritty Crime Drama Series

‘Shanty Town’ Review: Scalar But Lively Chidi Mokeme Saves The Day in Gritty Crime Drama Series

Jungle justice is a routine act in Nigeria; it takes little for any regular crowd anywhere in Nigeria to select an individual, any individual, and take the person’s life. But the incredible thing is how quickly the crowd dissolves into individuals of “normal” people, even the onlookers who did not participate, and how everyone returns home to their friends and families even though they have permanently made it impossible for someone else to do so. Rarely do people think about the dead victim beyond physical fact. Once the charred corpse is out of sight, it seldom comes to mind again. And if we rarely consider the corpse, why would we consider its relatives—wife, friends, children, siblings, or parents? This dismissal is necessary so that the weight of guilt is minimal and the return to “normalcy” can be seamless.

The victim ceases to be a person and becomes an outlet of national anger and frustration. A thief? Surely you have been robbed before, or you know someone or someone who knows someone who has been robbed before. And the anger from that injustice is now being visited on this victim. A blasphemer? Perhaps that’s why the country isn’t working. And so the act is justified—your direct participation in delivering that justice or your silent agreement to delivering that justice.

Little sense should be expected of the mob and its audience. Little help should be expected of the incompetent police force. But those who visit the crime scenes afterward, in pages of reporting or films of storytelling or essays of critical writing, should be paid attention to; they should have something important to say about that act. They should help us make sense of it. This is because artists and creators are expected to think about all parties when they make sense of such an event—the agitators and their victims. We arrive then at Linda Ikeji’s doorstep, one of the reflective visitors to a crime scene through her film Dark October.

The film follows four young, regular undergraduates. They have dreams of a music career. They were wrongfully lynched and immolated by a mob in ALUU after their debtor raised a false theft alarm. The movie ends.

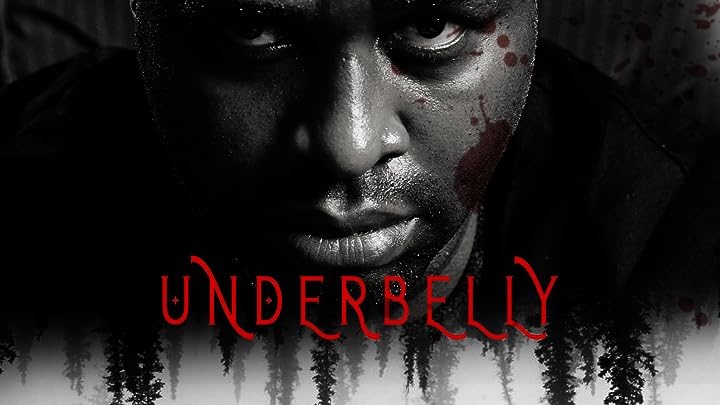

‘Underbelly’ Review: A Promising Period Drama with Unfulfilled Potential

‘Underbelly’ Review: A Promising Period Drama with Unfulfilled Potential

40 Most Anticipated Nollywood Films Coming in 2023

40 Most Anticipated Nollywood Films Coming in 2023

There is nothing wrong with a sparse plot, but I have deliberately whittled it here because it felt like the impending mob violence in the film was all the movie clung to, the only thing everything else was built around. Linda Ikeji—who doubled as producer and “story by”—and Odewa Shaga (screenplay) have written a bad film. The director, Toka McBaror (The Millions), has not covered this work in glory. These primary coordinators, credited to be creatively behind this true life story, Linda Ikeji, Odewa Shaga, and Toka McBaror, will be our concern here.

A good reference for a film of this nature would be Tunde Kelani’s Ayinla, which details the life and death of the infamous Yoruba musician, Ayinla Omowura. While the viewers went into the film knowing Ayinla would be murdered, the film itself was about Ayinla Omowura’s life. It didn’t feel this way in Dark October.

Let us praise the makeup for the opening and closing scenes. The props and costumes were also immaculate. And it appears everyone involved was willing to push the believability of property damages. These are regular feats of filmmaking rarely pursued in Nollywood.

The film stars Chuks Joseph, Okpara Munachi, Kelechukwu Oriaku, and Kem-Ajieh Ikechukwu as the lead characters. Their performances are generally superficial. Their acting feels uniform and interchangeable; their American accent, their 2 million sighs, their “bros,” their mannerisms, one of them could have played all the characters. There is little work done to delve deeper and become the character, and perhaps, little work done on the coordinators’ parts to make the actors understand that all the scenes before the lynching are more important than the lynching scene. But then, one gets the sense that perhaps they—the creative coordinators—might not have understood this as well.

The ambience itself, although familiar, feels suspect: students who don’t care about school because of a higher calling, a doting mother who doesn’t understand the dream, a doting girlfriend who doesn’t understand the dream, old-school, non-compliant lecturers, a cultist named Capo: essentially, university stereotypes thrown into a writer’s blender. What is that mic quality? Who are these amateur actors shoehorned into pivotal scenes? Why are half the lines in the film explaining the story? Why have you allowed the event of the lynching alone to define the movie and the lead characters? The list could go on, but we must ask ourselves a moral question.

This is the truth: the ALUU 4 story is a public event, and each artist can approach and tell it. But morality and common sense dictate some level of caution about approaching it. An example would be Teju Cole’s enlightening essay, “‘Perplexed … Perplexed’: On Mob Justice in Nigeria”. Or this honest De Tour YouTube video about the young men. Work of this nature must be approached, as an artist or as an articulator of the incident, with the memory of the boys and their families in mind. Trauma never ends, and all it takes is the wrinkle of a leaf a certain way or the sound of a familiar voice to revive grief.

It would be disingenuous to say Dark October is not about ALUU 4. Four students, Ugonna Obuzor, Lloyd Toku, Chiadika Biringa, and Tekena Elkanah, were necklaced by a mob in Aluu in 2012. To say names were changed and that there are no facts in the film is mischief at work. And this automatically denounces Linda Ikeji as an articulator of the incident and places her as an opportunist.

Multiple truths can exist: it is important to make films about jungle justice, to make films to commemorate the memory of the ALUU 4, but the empathy with which these films are made cannot be understated. Empathy is what separates the artist from the mob. And certain statements have demoted the integrity of this film from being a piece of commemoration to a cash-grab material.

Why was this film made? What unique statement has it made, lacking in artistic merit as it does, that hasn’t already been made in a visual medium? What social commentary does it make beyond vague, moral fence-sitting—painting the community chief as some Pontius Pilate? What has it done beyond living off the memory of a real tragic event and weaponising it for its climax and pathos? In the end, I did feel pity for the characters, but not from the work the writers or director did, only because I knew the ALUU 4 story before I saw the film, and I believe this would be the case for most.

In Dark October, we have a shabby film, shabbily thought out, and so executed. By the sixth minute, I was certain that a documentary should have been made instead; at least it would have forced the executors to take moral responsibility and ask questions of the community that allowed this; to force the viewer to empathise and see the family’s mourning; and to create a proper, three-dimensional image of those boys, their dreams, and the cessation of that dream by a community’s madness. I found little to none of these in the film. So I went in search of the boys, and I found them and their dreams here. You will too. And I promise you’ll find more empathy in it than you did in the 1 hr 49-minute runtime of Dark October.

Dark October is streaming on Netflix.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

I looked forward to this review😡, and you did justice to it.

Thank you Olamide