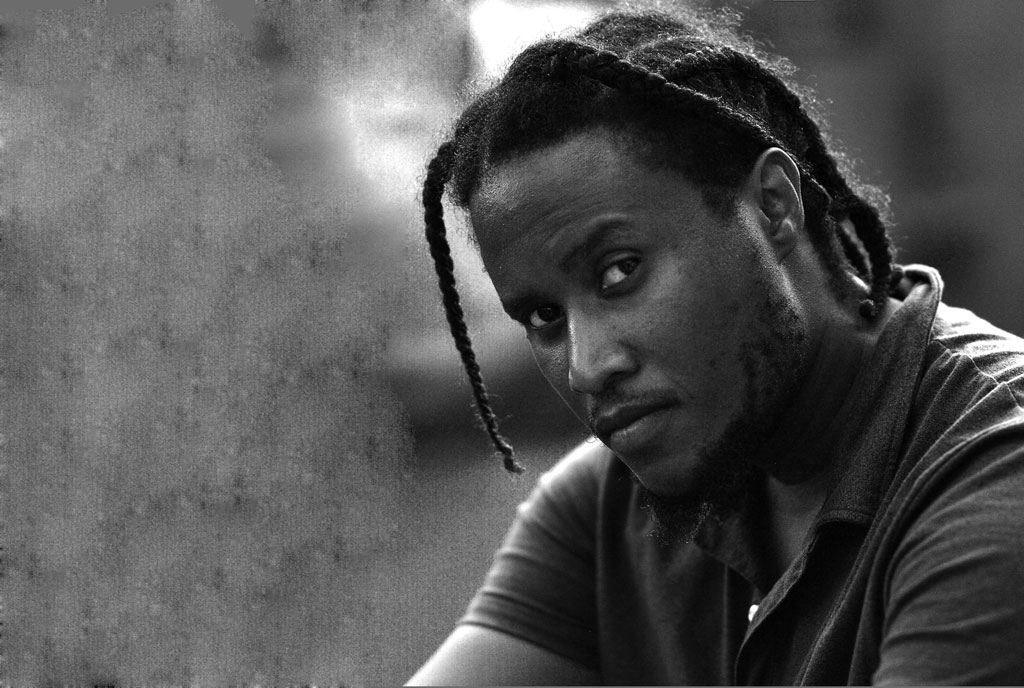

EXCLUSIVE: What happens when an artist is awfully quiet? Have they taken a hiatus to creatively rediscover themself, or have they simply ventured into something different? The former is the case with Daniel Oriahi, director of 2018 supernatural thriller Sylvia, whose name we have not seen on our screens for a while. “I took a break for a while. I needed to realign myself with why I love what I do—which is filmmaking—and the kind of stories I want to tell.”

Oriahi took a step back to teach young filmmakers directing at the Ebonylife Creative Academy, the Lagos state-sponsored film academy founded by media mogul Mo Abudu. “I feel like I’ve always been a collector. I’ve been collecting films for a very long time and exploring, getting to know about cinema and its history.” As a result of his habit, Oriahi adds that he feels like he is “more of a scholar than a filmmaker who goes into ‘the trenches’ to make films”.

Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis once said, “True teachers use themselves as bridges, over which they invite their students to cross. Then, having facilitated their crossing, fully collapse, encouraging them to build bridges of their own.” The role of mentoring cannot be undermined in filmmaking, and great filmmakers seek to mentor and be mentored. The list is endless: Steven Spielberg, for instance, mentored Robert Zemeckis, who in turn helped Peter Jackson. Roger Corman mentored Francis Ford Coppola, who went ahead to mentor George Lucas. Clearly, Oriahi is not oblivious to this. “When I was in my mid-20s, I realised that I didn’t really know film, and I felt like I started late. So, when I come into this kind of space and I see young people, I feel like I can start imparting that culture of film theory and other aspects of film that exposes them faster on how to express themselves as filmmakers.” On whether every filmmaker should take out time out of their career to teach, he responds: “Being a mentor doesn’t necessarily mean you have to stop doing what you do, but you can be a mentor by showing someone how you do your stuff. I wouldn’t say take time to teach, but take time to reflect on how you can improve yourself. What avenue can you use to improve yourself? Fortunately for me, it is teaching. Maybe I could have gone to a film school, because I had gotten to a point where I needed to take a step back and update myself as a filmmaker.”

The advent of film schools in Nigeria is an eye-opener, and there is no wonder at all that there has been a rise in film school investments in the past decade. A major advantage of a film school is the exposure of its students to the history and theories of film. Emphasizing this, Oriahi says: “You can’t take away the fact that film theory, film analysis, and film viewing are part of the characteristics that make a filmmaker, and when I had the opportunity to teach, I felt it was very important for students to understand these things. At the end of the day, that is the beauty of the character of a filmmaker. It builds you up because you are exposed to what has been done, what is being done and what is yet to be done. I have been trying as much as possible to share that film enthusiasm with young people and I know that it is always something I yearn for.”

It would be misleading to think that only mentees reap the benefits of good mentorship. Oriahi attests to this: “Teaching has equally opened me up more to what I truly desire: watching more movies and studying films from different parts of the world. It has shaped my intellect on how I want to tell my stories as against conforming to a rigid structure, be it Hollywood or Nollywood. It has helped me see the kind of filmmaker I want to become”. Mentorship benefits the mentor in so many ways including giving satisfaction; giving a new perspective and developing communication and leadership skills. These benefits are evident in Oriahi’s teaching journey. “I have evolved on how to pass information to people.” He adds, “I even feel like I am learning more than my students. You know, I get to do this frequently and by doing that, I am updating myself.”

One thing the House 5 Production founder has not failed to emphasize during the course of his coaching is the need for filmmakers, especially directors, to be vulnerable. “I mean being vulnerable in the sense that being honest and being objective about any subject from any perspective gives it authenticity, heart and soul. It starts with the filmmaker being open enough to share information because you require people around you to sacrifice something for what you are trying to achieve”. Vulnerability is a popular subject among filmmakers. Film producer Caroline Von Kuhn attests to this, “We chose to embrace our vulnerability, let go of our ego, judgement and voices of doubt, and simply open ourselves.” American-Mexican filmmaker Naomi Uman says: “That’s my main practice–making myself vulnerable”. Film writer Rob Hardy, says great filmmakers practice “courage and vulnerability by putting very real pieces of themselves out into the world.” The list of quotes on vulnerability goes on and on.

Oriahi, still, on the subject, “You need to be in a position where people around you can see that you’re 100% committed to achieving the vision. In doing that, you express some level of vulnerability in terms of the decisions you make. If we were in a country where the president regularly tries to engage the masses, rather than being in sirens, it will change our perspective on government or how we see what they’re doing. A leader has to be vulnerable, not dictatorial. Though filmmaking can easily fall into that line of dictatorship, you have to make a conscious decision to know that vulnerability is key”. Perhaps if more filmmakers had put this knowledge into practice, it would have hindered the horrible bosses episode that trended in early 2022, where people narrated nasty experiences they had with some filmmakers in the industry.

A question many filmmakers ask is “How do I balance making art and making profit?” Oriahi goes further to talk about seeing film as an art form, not just an avenue to make money. He gives a profound response: “We cannot deny the fact that we need the industrial set-up or structure to survive. Few African film industries apart from Nollywood have been able to create this platform where people can aspire to make films. We don’t have that in Gabon, Guinea, and the likes.” He adds, “It is a great thing that we have this establishment that we are able to make films regularly. However, such establishments require films to be profitable in order to thrive. Unfortunately, that can stifle a creative because you don’t necessarily want to tell those kinds of stories; you just want to express yourself in your own way. However, you cannot deny the reality of the fact that it is an industrial complex. At what point do you say ‘How do I define myself regardless of this complex?’” He proffers a solution, “There’s a mid-20th century German filmmaker I admire so much, who used to say, ‘Make one for them, make one for yourself’. And I say the same thing: Do one [film] for them, and do one [film] for yourself.”

One of the ways Nigerian filmmakers have made profit and celebrated milestones is through the successful theatrical release of their projects. However, streaming platforms such as Netflix are eating Nollywood’s lunch. When Daniel is asked about his opinion on cinema culture in Nigeria, he responds, “As a result of our upbringing—television—we did a lot of piracy work, and we were watching video on demand. So streaming is kind of where we were leaning to.” He further explains, “Nollywood emerged out of the revolution of digital filmmaking and we have been following that trajectory which is after the culture of exhibiting films through cinema. We are not going back to wanting to explore just that avenue of seeing films in the cinema. We are very open to what technology is bringing for us, and right now streaming is that thing.”

Loukman Ali: What Goes On in the Cinephile Mind of the Versed Ugandan Filmmaker?

Loukman Ali: What Goes On in the Cinephile Mind of the Versed Ugandan Filmmaker?

In 2019, the Cinema Exhibitors Association of Nigeria (CEAN) revealed that there was a high demand of foreign films by cinemagoers. About three years later, this has not changed. “Our cinema culture is still heavily reliant on American and foreign influences. A case in point is Wakanda Forever, one of the highest-grossing films of 2022. A Nigerian film would struggle to get to that point because people don’t necessarily identify Nigerian films in that format. I don’t think filmmakers aspire for that because when you look at the economics, it’s not as if they make a lot of money from cinema,” shares Oriahi.

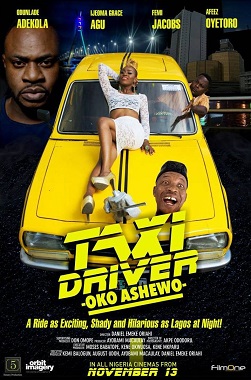

The Taxi Driver: Oko Ashewo director suggests, “We can stick to originality by really articulating the kind of stories we want to tell. We cannot deny the fact that this access can make us want to conform to telling stories that are globally articulated, so we have to work with stereotyped tropes and genres. We cannot deny our foundations: we are African, and we come from a multi-ethnic society and heritage. As African filmmakers, we need to be aware of where we come from, our personal influences, and how we can wrap that around our stories even when doing it for global accessibility. That is why when I teach, for instance, I always ask my students, ‘Who are you?’. Once you start accepting and being aware of your journey and history, you can start wrapping that around generic stories and telling them from that perspective. I think the journey is with the filmmakers.”

Oriahi doesn’t stop there. “Netflix is in vogue now, but in the next 15 years it’s going to be something else and that thing would demand a certain type of structure. If you want to evolve like that, great! But you have to have a foundation and rely on that. Every great filmmaker has a foundation. There are filmmakers that have been here for over 40 years and are still making films that have a piece of them. I feel like the best filmmakers are the ones that are well grounded in their identity.”

Identity has been a major topic among Africans, especially in these times when the world has more access to our films. When asked what he thinks about the western world telling African stories, Daniel Oriahi replies, “They would always tell stories if the stories are there to tell. I think the reason we get so upset about this is that we have limitations on stories from other parts of the world. There are stories that have been told from other parts of the world by people not necessarily from those places”. This is in fact true, as a perfect example would be American director Steve York’s documentary film A Force More Powerful. The documentary covers resistance movements in India, Denmark, South Africa, Poland and Chile, despite being written and directed by an American who has not experienced any of the struggles.

Daniel Oriahi continues, “It is equally wrong for us to tell stories from just one perspective. For instance, let’s talk about The Woman King. You cannot tell me that the Dahomey women are the only set of people in the history of the world that have stood up to defend themselves against external aggression. There are tribes from different parts of the world that have gone through similar struggles. This is something that is consistent with environment: exploitation and resistance. We’ve always had resistance: resistance from the Scandinavians, South African resistance, etc., and the truth is at the end of the day, these stories have one thing in common which is the human struggle. You can’t say another human cannot tell that generic story of human struggle or human identity or defiance to external aggression. We see it everywhere; it still happens till today.”

Late African-American historian John Henrik Clarke once said, “there has been a struggle to reclaim the African self”. Daniel says, “I just feel like we are holding on to ‘African stories’ because maybe we are struggling with our identity as a society. We have our culture and I can’t take away the fact that a lot of things have been taken from us. We have a very dark history as a people but the world has experienced a lot of things, and it’s okay if somebody else wants to tell the stories that people everywhere can relate to. I think it’s a success.” Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa once shared similar thoughts using different words: “Human beings share the same common problems. A film can only be understood if it depicts this properly.”

Daniel Oriahi reveals that he is currently working on a project titled The Weekend, which stars Bucci Franklin, Uzoamaka Aniunoh, Meg Otanwa, and Gloria Anozie-Young among others. He hints that the film is “about the secrets we keep in relationships, and how they can end up being very tragic to the people involved in the relationship. It’s about family dynamics and keeping up with family heritage. It has a political undertone as it deals with political, social and cultural trauma”. The principal photography took place in November 2022, and he admits, “well, to be honest, the experience was very humbling, and I did some really interesting things with my craft. We had close to 150 people on this set, which makes it the biggest set I’ve been on and the second biggest project I have embarked on. The first was a Netflix project but unfortunately, it got canceled because of COVID. I was comfortable and familiar on this set because the film primarily takes place in a house which is a small space”.

When asked what new experience he had while on this set, he responds “I think the experience was getting to find interesting ways to explore limited and confined spaces, as the film is set in one house. We had to make that work. Also, in terms of character journey, it was interesting to see how the film became about two people in a relationship. Initially when I was reading it, one of the characters felt weak and I leaned more toward the character and wanted to elevate the character’s arc and structure so that we could really empathize with her journey. During the shoot, it became very clear that it was not just her (Uzoamaka), but equally her partner (Bucci) that were going through a journey. I had to interpret that visually so that we saw the journey from both perspectives, distinctively and as a comprehensive whole. I found that interesting as that was discovered while making the film.”

Though The Weekend has horror and psychological thriller elements similar to Sylvia, Oriahi assures that The Weekend is different from Sylvia or any of his works you’ve seen before. “I would say it is how audacious the film is in execution. It is a horror film and it has some elements that I want to keep holding on to as much as I can, so that there is shock value and repulsion for the audience. I feel that is what I will achieve with this film. The audaciousness gives it an edge, and it’s the most visually satisfying film that I have done. I know it is going to be beautiful, but at the same time horrific for a lot of people. There were many themes which I feel were clearly expressed this time which will make the audience go ‘wow!’. So it’s so different from Sylvia, because I feel Sylvia was very restrained.”

As a result of his reinvention, one would expect to see fresh directorial decisions reflected in this new film. Oriahi explains, “I really don’t know. It’s not like I’m being intentional about how I want to express myself now as a filmmaker or make a distinction between what I was and what I am now. But I feel that to a very large extent, I was more precise on what I wanted to interpret visually in terms of character journey and the whole mise-en-scene in the film. It was very clear from the prep stage how I was able to clearly articulate what direction the film was going to go visually. I know this is going to stand out when the film is seen by other people. At the same time, it’s like a fear or concern that the film is made in post-production. And you have to come to terms with a lot of the decisions you made and see if it is working. We, fortunately, had an editor making stitches for scenes as we were shooting, and it made a lot of things clear for us. It makes me hopeful regardless of my fears and concerns”. He adds that he expects to have the first cut by the end of January. Trino Motion Pictures (The Razz Guy, The One for Sarah, Sylvia) is the production house behind the film.

Oriahi definitely has a lot of things in store for the audience. He also lifts the lid on yet another project: “At the moment I’m developing a personal project titled “Black Custodian”, which I’ve been working on since 2019. It has elements of supernatural, thriller, crime and psychological drama. It’s about a guy who returns from a failed trip to Europe and deals with PTSD.” With these projects lined up by the reflective filmmaker, we surely can’t wait to see Daniel Oriahi’s name roll in the credits again.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

1 Comment