One of the things film can help us do as a people is reckon with the past. Events which seem to have been forgotten can be brought to the fore through the power of narrative, becoming, even for a brief moment, the principal object of social discourse, and by the same token, an entry point into that period in history, as well as an opportunity for deep reflection. Sometimes, the number of films being made about a particular occurrence is able to reach critical mass; when this happens, it means that said occurrence now holds such a prominent position in the public consciousness that you would be hard-pressed to find anyone who couldn’t name a handful of films about it. Take the Holocaust for instance, about which at least 440 narrative films have been produced.

‘A Japa Tale’ Review: Too Contained For Its Own Good

‘A Japa Tale’ Review: Too Contained For Its Own Good

Andrei Tarkovsky, the late Soviet filmmaker, once had this to say about the nature of time: “In a certain sense the past is far more real, or at any rate more stable, more resilient than the present. The present slips and vanishes like sand between the fingers, acquiring material weight, only in its recollection.” What cinema can do is facilitate such a recollection on a mass scale, putting both recent and distant history into context, enabling us to look back with the benefit of hindsight. Across various eras, humans have always told stories to better understand the world around them, and our modern age is no different. The COVID-19 pandemic has already been the subject of a good number of films and stories, and we can only expect more to be released as time goes on.

Nigerians had more than just the pandemic to contend with in 2020. In the midst of worldwide protests against police brutality and other civil rights issues, the EndSARS protests, a decentralized movement taking a stand against oppression from national security forces in general, simmered and then exploded, the shockwaves reaching beyond the country’s shores to Nigerians in diaspora. The Lekki Massacre which was initially denied, then later acknowledged, by the government, represented the climax of the struggle between two forces, one unstoppable, the other seemingly immovable; one armed with placards and songs, the other with live rounds. The image of a bloodied flag is no doubt burned into the minds of every young citizen, as a simultaneously literal and symbolic rejection of peace by the powers that be– public servants, elected officials, not gods.

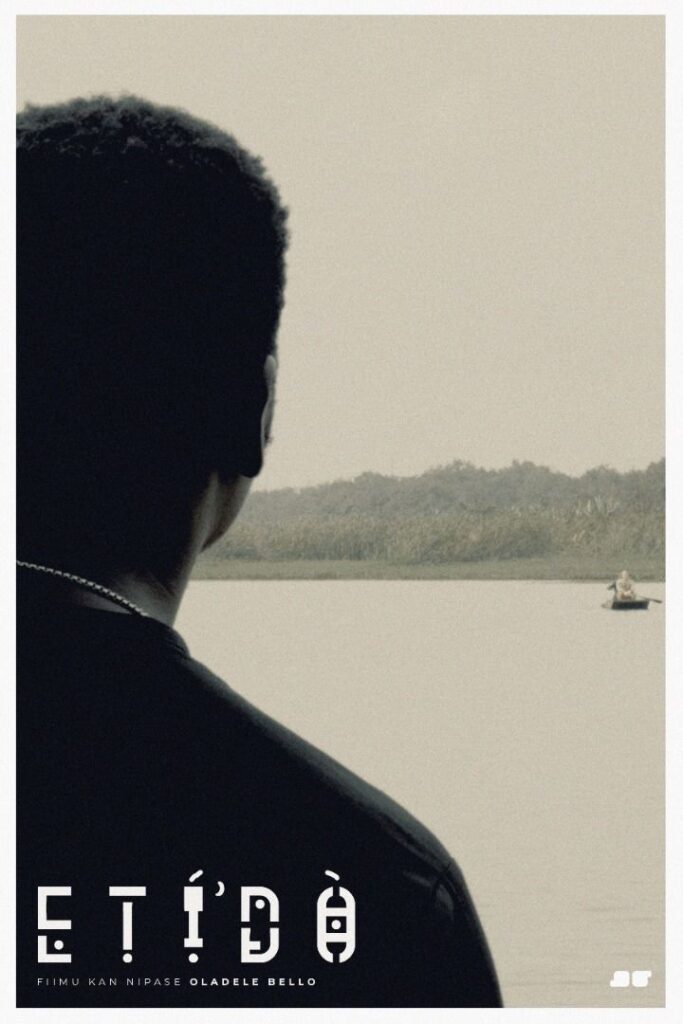

It’s been two years since the tragic incident and in that time, more than a few Nigerian writers and filmmakers have cast a backward glance at that period. ‘Chukwu Martin, in his rough play, Mr. Gbenga’s Hard Drive (2021), sets his story of a hapless accountant doomed to an odyssey of an existence at the time of the nationwide protests, even splicing the narrative with real footage obtained back then. In November 2021, Samuel Adeoye’s film, Abdul, released to mark the first anniversary of the #EndSARS protests, premiered at AFRIFF; the story follows the titular character, a 24-year-old Nigerian who finds it safer to stay behind bars abroad than return to his fatherland. The film, with its fast-paced editing and formalist-heavy style, is centered on the protests and the dreadful reality of that period. In Eti’do, Oladele Bello decides to go in a different direction, creating a 7-minute short film that manages to touch on everything from the upcoming elections and the power of social media to effect change to the plight of Nigerians struggling to make a living even as they clamor for a better tomorrow, without actually showing one shot of a protest march. It has moments where it shines and moments where certain decisions hold it back.

The film starts with a voiceover; a man on a radio is recounting his experience during the protests. He sees his friends “falling on both sides” and in a frantic attempt to escape, he jumps into the lagoon beside the tollgate. This is a good way to begin the story as it sets the mood for the proceedings. Two young men,“ex-protesters,” like the director calls them, meet at the riverside. They happen to recognize each other from the protest demonstrations and a conversation ensues as they wait for their turn to embark on an important journey to the other side.

One of them criticizes the other for selling cardboards at a markup during the protests, and the other defends himself, saying he needed to make a living. In response to the second man dismissing going viral online as overrated, the first extols the power of social media (which one suspects is an attempt by the writer-director to underscore how important a tool it was during the protests), going as far to say, “Do you think Twitter was banned by them just for the fun of it?” The actors do a good job with these characters, emoting and delivering their lines in a manner usually reserved for theatrical productions; however, this decision works because the filmmakers combine this overt display with more subtlety in other areas, such as the cinematography (the motion blur has a positive effect, adding to the sense that the conversation is not exactly taking place under normal circumstances).

The decision to keep the dialogue (and indeed, the credits and other text that appears in the film) in Yoruba is a welcome one, adding much-needed verisimilitude and authenticity to the proceedings.

If I have any critique of Eti’do, it is that the dialogue feels rushed and on-the-nose. Bello is trying to touch on so many things in a short period that the final product leaves a little to be desired. After hinting that one of the men might have had a hand in disrupting the protests, causing them to become more violent, the story just moves on, glossing over such an integral and important part of the EndSARS demonstrations. This information is supposed to humanize the character and show him as an ordinary person who will do what he can to survive (and as someone whose desperation was no doubt exploited by the same people who are largely responsible for it). But by refusing to flesh out this aspect, the writer-director, in attempting to shine a light on that situation, merely creates a spark, failing to provide fuel or kindling to keep it going.

The film’s structure also gets in its way. Halfway, there is a cut to a scene of a woman mourning one of the characters (we later learn that she is pregnant) but it comes across as a half-hearted attempt to instill some emotionality into the film; the part with the crying woman seems at odds with the direct, almost-cold presentation of the conversation between the young men.

First Look: Fatimah Binta Gimsay Announces Fourth Short Film, ‘Omozi’, Starring Teniola Aladese

First Look: Fatimah Binta Gimsay Announces Fourth Short Film, ‘Omozi’, Starring Teniola Aladese

Short Film Review: Biddy-da-dum, ‘BOO’D UP’ Delivers an Engaging Watch

Short Film Review: Biddy-da-dum, ‘BOO’D UP’ Delivers an Engaging Watch

The rules of the story world are also not properly established or communicated. Are they both aware that they are about to enter their eternal sleep (because the film suggests they are)? And if they are, how do they feel about it? About halfway through the film, one of the men says that he finds the forests where they are peaceful, compared to the place where terrorists and kidnappers are. The other man responds that all that is meaningless now. This is a sad implication in itself because the first man is essentially willing to face the uncertainty of the afterlife more than the hardship that comes with being Nigerian. Many storytellers have expressed the opinion that Nigeria is hell, and all the demons are here, and echoes of this come through in Eti’do.

However, this moment again is very touch-and-go, passing without much opportunity on the writer’s part to explore it further or with a little more detail compared to the rest. The film needed to use its premise to investigate more about the human condition (as witnessed in chaotic Nigeria). Are the men angry that they lost their lives fighting for the country? If they aren’t, why not? Are they sad? Disappointed? Scared about the finality of death, and their utter blankness about what exists on the other side? What about their families? How do they feel about never seeing them again?

Eti’do needed to engage with the audience not just on the level it presents to them but also on an existential one. It’s a film about death, after all. However, it seems like all there is to it is text and not enough subtext, nevermind a philosophical underpinning. One character mentions that the painful thing about dying, presumably, to him, is that he cannot vote anymore (that’s not remotely the saddest thing about dying); when asked which candidate he’d have voted for, he describes a “politician who wears glasses”. At this point, the text crosses the barrier into full-blown commentary, as unsubtle in its messaging as an early morning news report.

Still, the importance of films and other creative projects like Eti’do cannot be overemphasized. In Reekado Banks’ Ozumba Mbadiwe, he sings in the second verse, “October 20, 2020 something happened with the government, they think say we forget. For where, for Ozumba Mbadiwe.” Ozumba Mbadiwe is a road on Lagos Island that leads to Lekki Toll Gate, and that part of the song was an attempt by the artiste, in a popular medium, to recall the brutality of that night.

There are a lot of things in our past as a country that we need to come to terms with and try to understand and tell the truth about, and Oladele Bello’s Eti’do is the latest in what one hopes is a long line of stories that do just that.

One of my favorite quotes by a filmmaker comes from Jean Cocteau: “Film will become an art when its materials are as inexpensive as pen and paper.” Of course, there are still cameras that are as costlier than caviar, but the prevalence of android phones together with easy-to-use editing software has hugely democratized the filmmaking process. Not exactly pen and paper, but they will do.

We need more filmmakers shining a light on the various specificities of our condition, as well as ways in which we are just like everyone else; we need them, in unpatronizing ways, to talk about our beauty and our pain, our resilience and our Sisyphean struggle, our dreams and our disasters. The time is now.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Watch the short film below

1 Comment