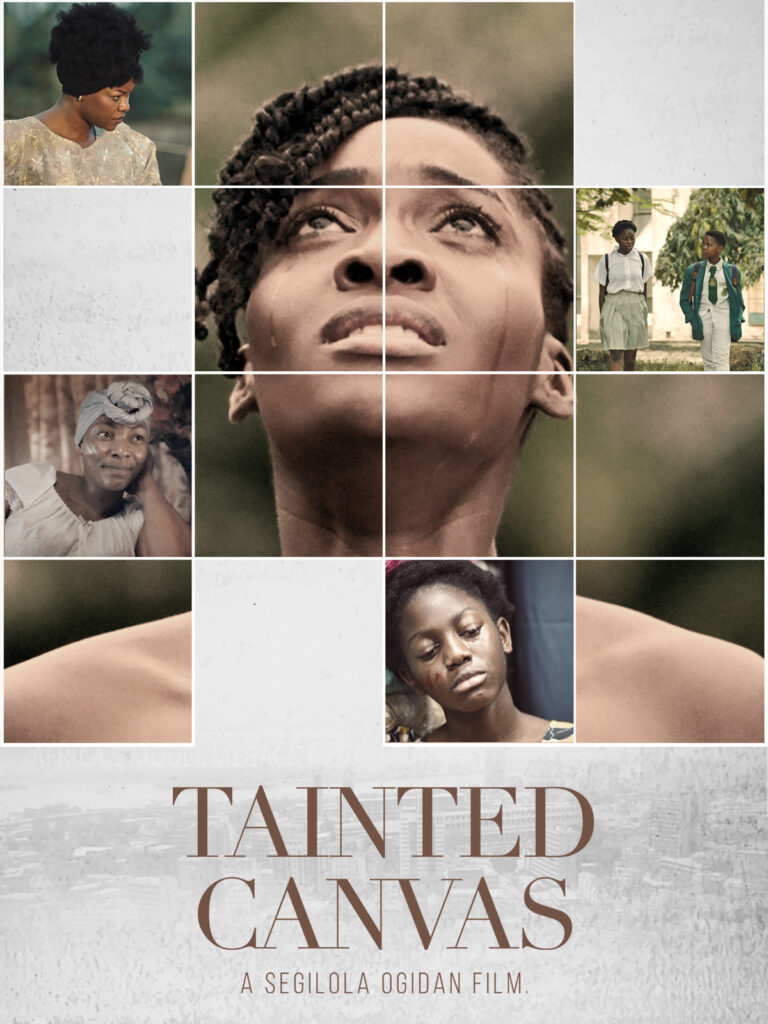

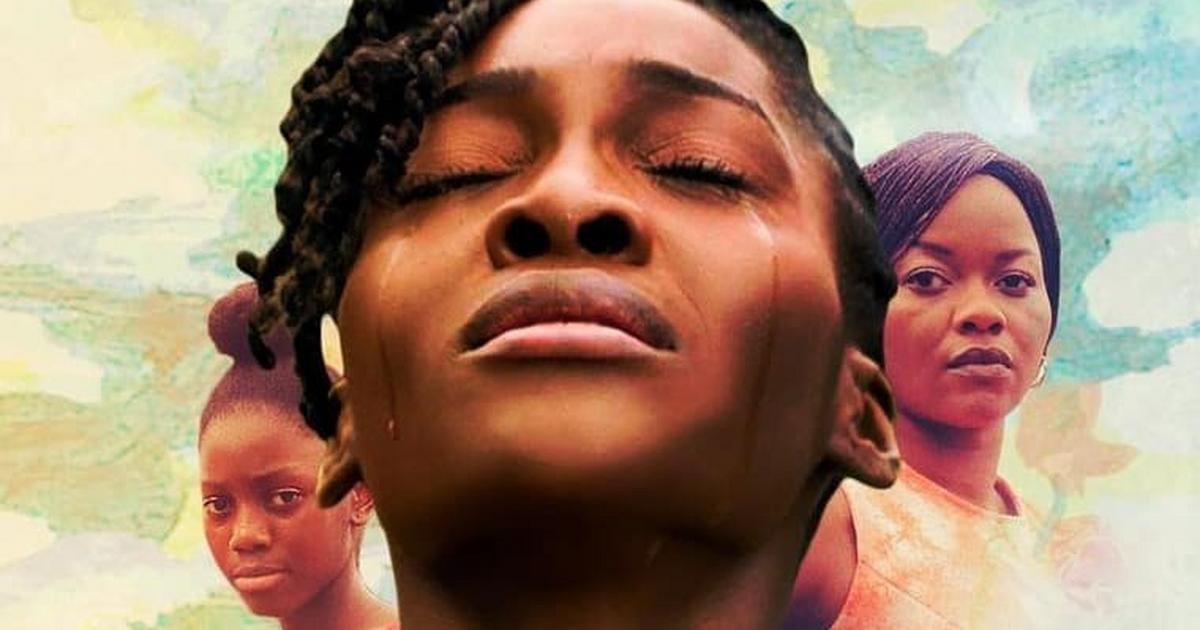

The day before I saw Tainted Canvas, I settled down to watch Babylon (2022), the latest outing from Damien Chazelle, known for La La Land (2017) and Whiplash (2014). I say ‘settled down’ because at just over three hours long, Babylon is the kind of flick you have to plan ahead to watch, fighting tooth and nail to carve out time in your schedule– it’s up there with The Irishman (2019), Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021), and the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Babylon, with a 56% score on Rotten Tomatoes, was released to mixed reviews; while some critics lauded its spectacle and humanist thesis, others, like Scott Menzel, called it “an ambitious mess of a film.” And this is the phrase that best describes Tainted Canvas, a film which is no doubt impressive in its decision to charge into the nightmarish corners of family and society, running the whole gamut of human emotion through its characters in the process– a film which thoroughly disappoints in its execution, resulting in an unwieldy, confusing mess.

-Spoiler Alert-

In the first shot of the film, we see a young girl, Morayo, on a field at school, eating sand while wearing a look of disgust. A boy who sees her comments on the scenario: “That’s disgusting.” The girl tells him off and goes back to eating. She is doing this for a reason, to protect herself from a predator. After informing us that the story was “inspired by true events,” the film shifts gears to the present day. Morayo, now a young adult (played by writer-director Segilola Ogidan), has returned to the country at the request of her aunt (Tina Mba); her mother (Kehinde Bankole) is sick– cancer.

However, she and her mother are not on speaking terms, and later that night, while they’re having a conversation, Morayo’s aunt begs her to forgive her mother. At this point, the audience’s interest is piqued; what exactly happened between Morayo and Rose, her mother, and will the former forgive the latter before the credits roll? This is the stuff of simple, good dramas. With excellent performances and a passionate, self-aware direction, the film could have been a home run. Sadly, Tainted Canvas becomes something else entirely, a messy, incoherent assortment of scenes whose story appears to work against its message. You get the feeling that the film thinks itself daring and bold and important for choosing to explore topics like depression, unhealthy family dynamics, sexual and physical abuse, and PTSD; however, it is not enough to merely include these elements in a story. They need to be approached with painstaking care and nuance. Tainted Canvas seems at a loss as to how to go about that.

I mentioned in the title that the film’s message is important, and more than that, it’s both timely and timeless. At about the 11-minute mark, Morayo, in her voiceover, says: “Every individual has the opportunity to be a masterpiece. A baby is born with a clean white canvas full of unlimited opportunities. But an adult has a paintbox of experiences, of many colours that change their picture over time. Depending on the brushes used during their life painting, some are left with a beautiful work of art, whilst others are grotesque, tainted.” Now, if this had been a short film, and it had ended with the main character saying the above in a monologue or voiceover, it just might have worked, but as it stands, there are still eighty minutes of movie left to go and we have just been told the core thesis of the film by the protagonist. What else is there to say? Plenty, it turns out.

We learn that the reason Morayo is eating sand at the beginning is because of her teacher, who regularly molests her and abuses her physically and mentally by locking her in a box in class. Pleas to her mother to put an end to this fall on deaf ears, as she dismisses Morayo’s claims as lies. We also learn that the reason Rose, Morayo’s mother, acts erratic most of the time is because she is suffering from clinical depression and is on antidepressants. In one particularly heinous sequence, Rose discovers that her medication has finished. Unable to afford the prescriptions, she tricks Morayo into getting molested by a cloth trader in the market. She sits in the shop while the man, presumably in his 30’s, has his way with her daughter, all so she can get some money for her antidepressants. At least that’s what the film tells us. We also later learn that Rose never wanted a child, and even suffered postpartum depression when Morayo was born. In a scene so hamfisted, it qualifies as failed Oscar-bait, Rose, recovering from chemotherapy in a hospital bed, tells her daughter: “I never wanted you…I still don’t want you.”

There’s no issue with not wanting a child. None whatsoever. The problem with the narrative is that the film tries to justify Rose’s heinous actions by informing us that in addition to her depression and trauma, she never wanted a child. But those reasons do not explain away the fact that she took her preteen daughter to get sexually assaulted in a market stall. After the deed, Rose goes to meet Morayo and sees that she is covered in blood. Furious, she goes to meet the cloth seller, Tony, and throws a complaint at him: “What I saw inside there (referring to the blood) is not how it’s supposed to be…you could have been more gentle.” Again, I ask, why does the film want me to understand this character’s point of view (without doing the work to show me why the character is acting this way)?

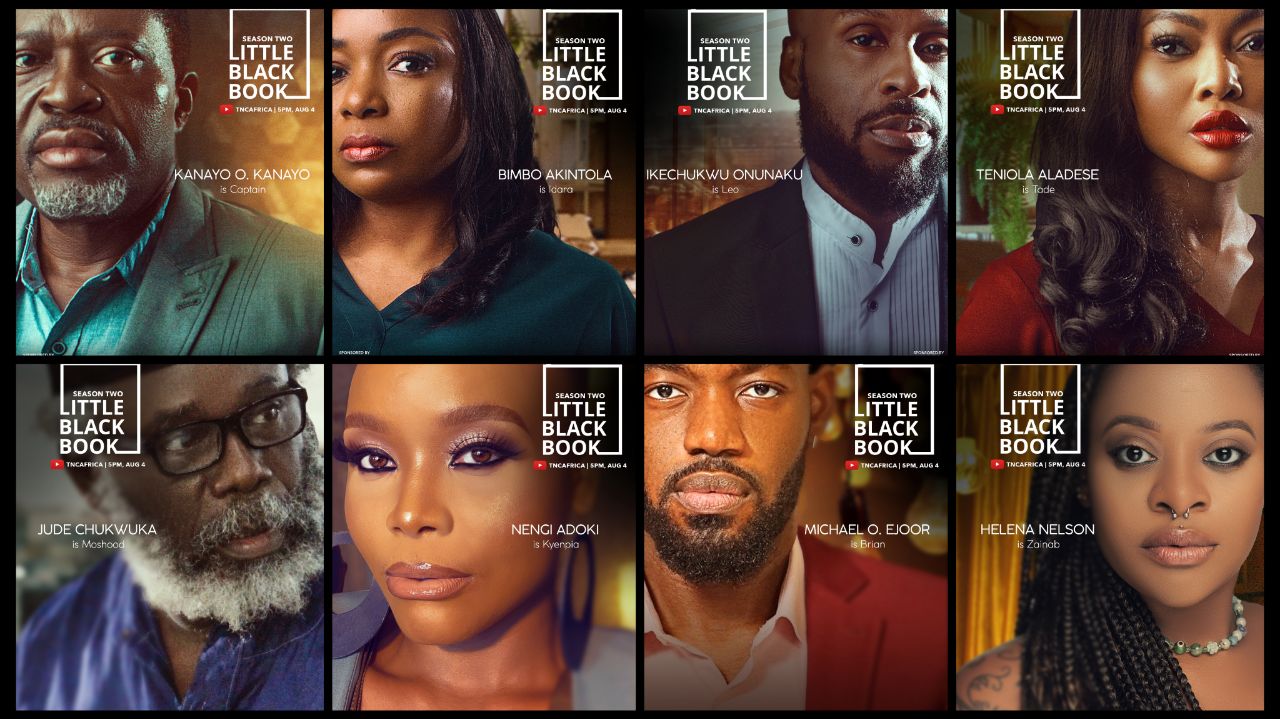

2022 Nollywood Cinema Films Already Streaming on Netflix and Prime Video

2022 Nollywood Cinema Films Already Streaming on Netflix and Prime Video

Take King of Boys (2018) for instance. Eniola Salami’s behaviour is far from saintly, ranging from questionable to downright abominable. However, almost immediately after the scene where Adetiba shows her killing a man in cold blood with a party carrying on outside, we are treated to the beginning of her backstory, an opportunity to see the whole picture of the character, to contextualize her actions in the present day. Sometimes, there’s no backstory, as in Jade Osiberu’s latest film, The Trade, but the characterization is done through action and compelling performance. Tainted Canvas fails to show us why Rose gets so depressed (all we get is a scene where the aunt essentially narrates Morayo’s backstory to Rose and I daresay that it doesn’t suffice as an explanation for Rose’s actions, or the justification the film wants it to be) that she is willing to give her daughter to be assaulted for money, and yet, it expects us to be sympathetic to that action. It’s less about the morality of the action (audiences are treated to antiheroes from stage to TV to the big screen all the time) and more about the weakness of the characterization; if you expect us to, together with Morayo, forgive Rose, you need to spend time showing why Rose acted the way she did.

In the hospital, we meet the doctor (Efa Iwara) attending to Rose, and the story jackknifes into a romantic subplot. The aunt encourages Dr. Fola to take Morayo on a date to a gallery or something of that nature, because “she loves art” and “she needs it,” so, “she will agree.”. He does. She accepts. They go on a date. Stare at a painting, and then each other (thus exposing their utter lack of chemistry). He tries to kiss her. She pulls away. He apologizes. He apologizes again the following day, but not before telling her that she should open a gallery (1999 called, and they don’t want their soppy romantic comedy trope back, just to ask why you have included it here, especially since it is never sufficiently set up and is never mentioned again). Fola also tells Morayo to “take it easy on her,” referring to Rose, “at least while she’s recovering.” I highly disagree. She needs answers. She should get them before the woman dies.

When Morayo and her mother are alone, the former says, “…if you loved me…you wouldn’t have let those things happen,” and she’s right. Rose dismisses her, saying, “I don’t deserve to be your mother,” but we can’t tell whether she’s only convinced herself of that fact or she truly feels that way, because almost immediately Morayo leaves, Rose is calling her back and calling for a nurse to help her up so she can go after her daughter. Her motivation in this scene alone is bound to give you cinematic whiplash.

Spoiler alert: Rose dies. And at the funeral, Morayo looks to the sky and says, “I forgive you. Say hi to dad for me.” Is she forgiving her because she just needs to move on (and is therefore doing it for her own peace of mind), or she genuinely can relate to why her mother did those things, including pimping her out for money, and has forgiven all? Rose doesn’t even apologize when they see each other in person. The forgiveness comes out of nowhere is all I’m saying. At the end, Morayo receives a package and her aunt tells her that she is the recipient of Rose’s life insurance policy payout. There is also a letter from her mum where she says, “My child, I love you…I pray one day you can forgive me.” Morayo sheds tears at this and her aunt says to her, “I told you she loved you.” Clearly, she has an opposite way of showing her love.

Tainted Canvas wants to, through Rose, portray the realities of clinical depression, creating a sense of empathy in the process, but in its fumbled execution, it shows people living with depression as deliberately wicked, even to the point of willfully harming their child. The whole story hinges on whether or not you believe in the world and the characters and whether you can get behind either Morayo’s need for healing and closure, or Rose’s volatile behaviour (and her depression being the reason behind this), but I didn’t buy one second of it. Not for one moment.

Referring to the over-the-top gruesomeness of the portrayal of war in All Quiet on the Western Front, Glenn Kenny, writing for rogerebert.com, says, “Filmmakers have arguably lost the plot, turning “War is hell” into a “Can you top this?” competition.” And this rings true in Tainted Canvas. The film falls over itself trying to depict dark and gruesome occurrences and after a while, it seems to forget why it’s doing that in the first place. Its message and aim to create more public awareness of heinous acts like child sexual abuse, are noble and good. As a matter of fact, like I said in my reviews of Reflections, Memories From Others, and Samaria (a really good short film you can watch here), we don’t have enough stories about this societal evil. We need more filmmakers telling nuanced tales of characters who find themselves victims of such wickedness, but they have to be done well.

I realize Tainted Canvas is inspired by true events and is in many ways not even as strange and harrowing as reality, but in film form, the relaying of this story does not translate well. I wish the cast and crew the best going forward, and anyone who’s been in similar shoes as Morayo, all the help and healing they need.

Tainted Canvas is streaming on Prime Video.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

1 Comment