Iranian visual artist Shirin Neshat once said, “Magical realism allows an artist like myself to inject layers of meaning without being obvious. In American culture, where there is freedom of expression, this approach may seem forced, unnecessary and misunderstood. But this system of communication has become very Iranian.” Even though magical realism was coined by Franz Roh, a German art critic, in 1925, to describe a method of painting which strayed away from realism, it did not become a movement until the 1950s when its style became popular among writers in Latin America and the Caribbean who blended elements of French surrealism with the indigenous mythologies from their various cultures.

In stories categorized under magical realism, there is an undercurrent of magical or fantastical elements existing side by side with the real world. According to Kristin Bair O’Keeffe, a magically realistic story is one that is deeply grounded in a realistic place and situation but in which odd, unusual and magical events occur. Notable works of magical realism include Amelie (2001) directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, The Lost Okoroshi (2019) by Abba T. Makama, “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel Garcia Márquez, “Like Water for Chocolate” by Laura Esquivel, “Midnight’s Children” by Salman Rushdie and “The Famished Road” by Ben Okri.

Related:

Movie Review: ‘Juju Stories’ is an Occultic Rhapsody

Movie Review: ‘Juju Stories’ is an Occultic Rhapsody

Apart from having threads of fantasy woven into a real and familiar setting, there are other features of magical realism such as a unique plot structure, limited explanation of the fantastical elements, if any, and a critique of politics and the powerful elite at the top. Latin American writers used their magical realism stories to speak out against the exploitation of their lands and oppression of their people by Western countries.

“The Famished Road” which won the Booker Prize in 1991 is set in Nigeria, pre-independence. The protagonist, Azaro, is an abiku, a spirit-child who experiences the mundane aspects of his environment together with the surreal, the everyday with the nightmarish; there are times he quite literally falls into other people’s dreams. This juxtaposition of seemingly opposite elements isn’t without substance or reason; Okri uses his story world to critique the state of things in the country, a protest in book form, raging against the colonial machine and the budding seeds of corruption planted by them. Isn’t it unthinkable that a place as rich in human and natural resources as Nigeria is still having the same conversations about economic growth and development that it was having decades ago? isn’t it almost surreal? Okri presents these questions implicitly, injecting “layers of meaning without being obvious,” an approach Abba T. Makama takes in “Yam”, one of the chapters in Juju Stories, the anthology by Surreal16, the Nigerian filmmaking trio.

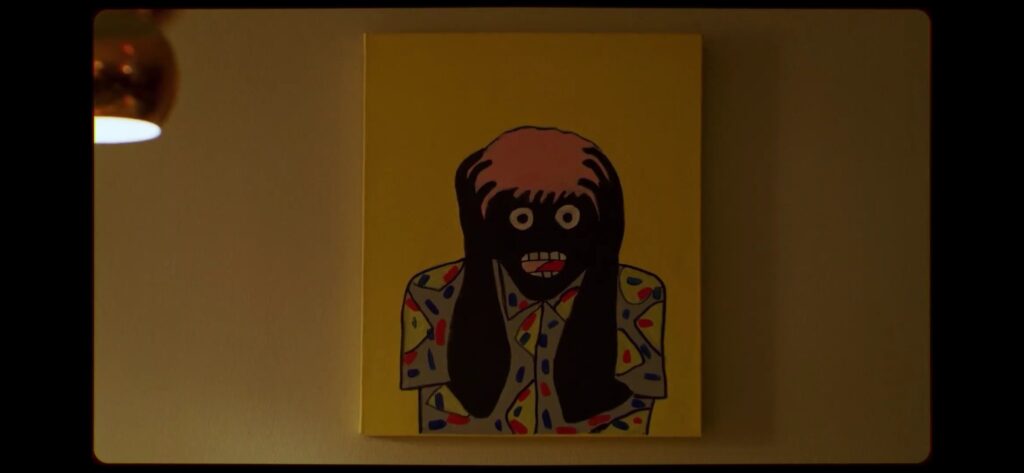

“Yam” begins with a reimagining of Edvard Munch’s famous painting, “The Scream”, in the center of the frame. And then the camera dollies out to reveal a couple (Uzoamaka Aniunoh and Okey Michael Ejoor) seated at the dining table in their home. A houseboy attends to them. These are upper-class people. From a newspaper, they read out an interesting headline about people mysteriously turning to tubers of yam after picking up some money from the ground. It is obvious from their demeanor that they are far removed from such a reality. Although they reside in Nigeria, their wealth and status has shielded them to an extent from such nightmarish events.

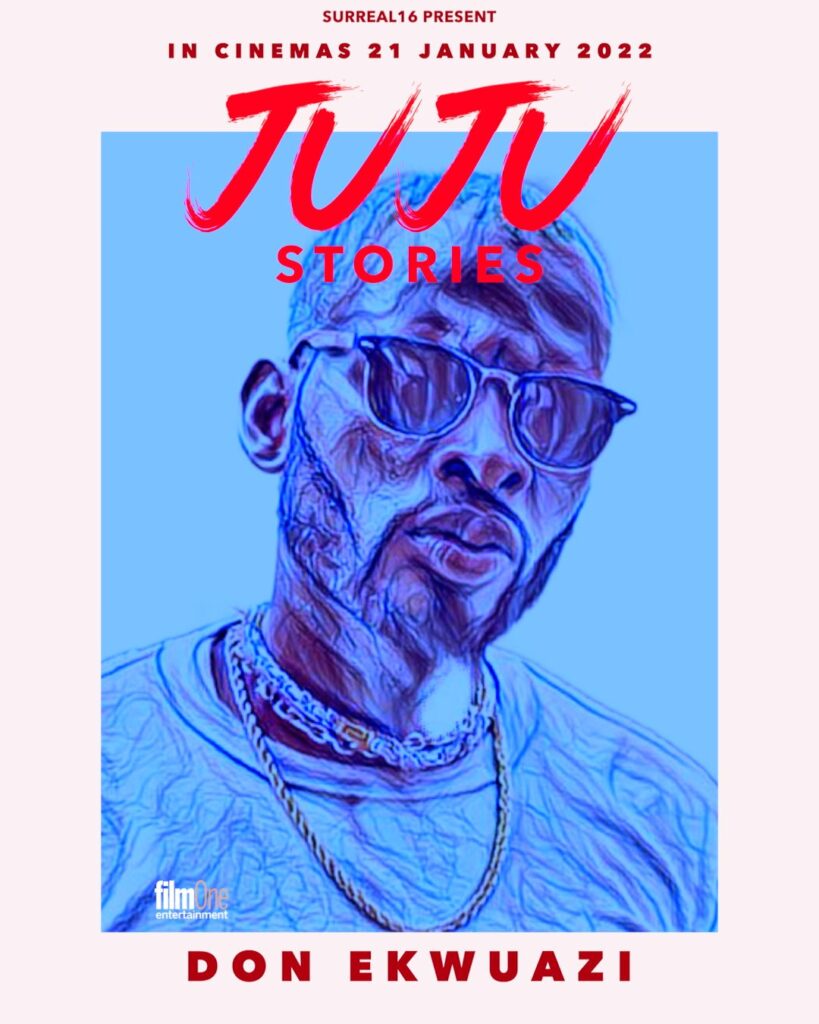

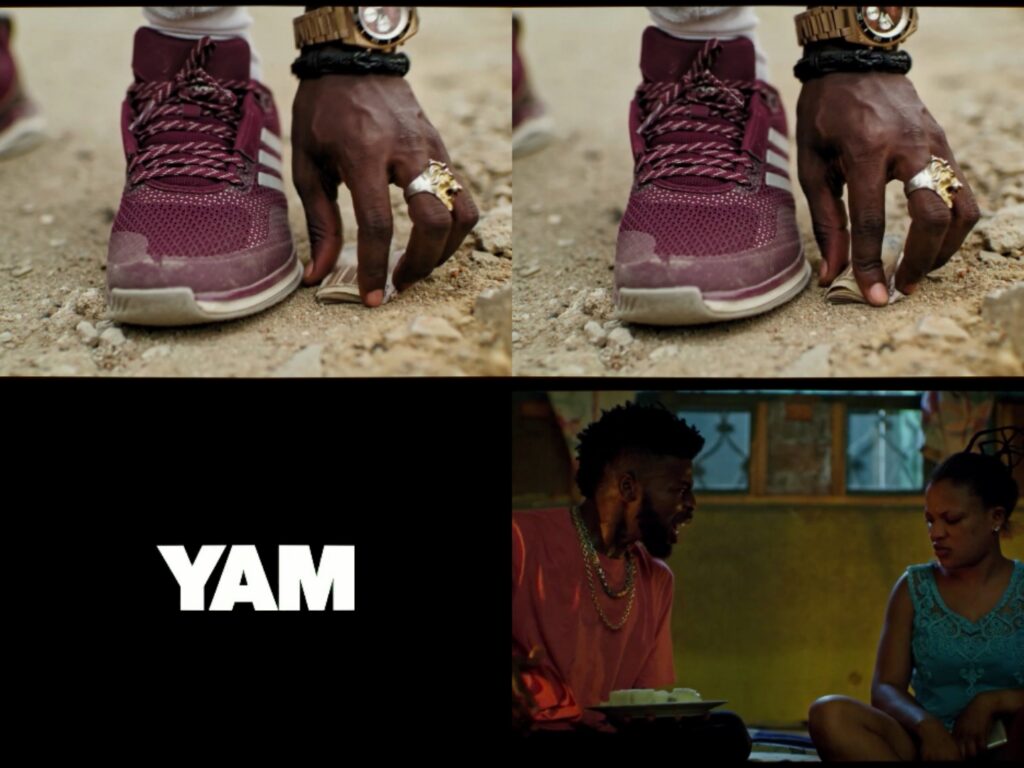

The story continues, this time following people living in the ghetto: a vulcanizer (Elvis Poko) whose girlfriend (Valerie Dish) is pregnant, and a street urchin (Don Ekwuazi) who hangs about the neighborhood. The movie plays fast and loose with time and space, in magical realist fashion. The camera constantly frames these characters in extreme close-ups and holds for an uncomfortable length of time. This contrasts sharply with the staging and blocking of the upper-class couple whom the camera keeps at arm’s length, cold and distant; we do not even see their faces very well.

Related:

‘Chief Daddy 2’ Review: Perhaps This is What the Audience Deserves

‘Chief Daddy 2’ Review: Perhaps This is What the Audience Deserves

After the person who picks money off the ground turns to a tuber of yam, the vulcanizer takes the yam home and prepares a dish with it. His girlfriend storms out, refusing to eat the meal he’s prepared because she doesn’t trust its origin. The scene where he goes crazy hearing the voice of the person who turned to a tuber of yam, the person he essentially sliced, boiled in water and ate with eggs, is extremely visceral. The screams of the first guy blend with the incessant questions (“where you dey?) of the second. The camera tilts at a disturbing angle, unmoving, a passive observer of madness unfolding. The guy turns the entire room upside down looking for the source of the voice. This scene goes on for a while. Every time you think it will cut to another one, to give some much-needed space to breathe, it carries on, boxing you in. The icing on the cake is several jump cuts which give the impression that even longer time has passed than what is being experienced by the audience. Brilliant, effective visual storytelling.

It is equally interesting and impressive how Makama is able to take a popular tale, one that is told to children in the country in an attempt to scare them, and reframe it as a critique of Nigerian society. The film does not attempt to present such an occurrence as fact or even question its validity, the goal here is to show the absurdity and unfairness in the contrast between the magical and the mundane. The condition of things in the country is brutal, the evil is borderline Lovecraftian, and yet these invisible powers have a very human origin.

If you attempt to pick up money from the ground (because your situation demands it) you get turned into a tuber of yam. And if someone else takes the yam home to prepare dinner for his pregnant girlfriend, he goes mad from the frightened voice of the poor soul wailing in his head, their fates inextricably linked. The grass suffers when elephants wrestle and whatnot.

“Yam” ends with a crossfade from the madman holding his ears, screaming, to the painting in the couple’s dining room. There’s another bit of news in the papers: there’s been an uptick in the number of mad people roaming the streets of Lagos. Again, it’s nothing but a slight inconvenience to them. This point is driven home in the final shot when after the bloodcurdling screams reach a crescendo, the painting falls to the ground (a metaphor for the suffering of the common man reaching a tipping point). All they have to do is get their houseboy to hang it up again. They don’t even have to get up from their food.

Wikipedia defines magical realism as what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe. Makama, in “Yam”, like Okri and Marquez before him, epitomizes that definition beautifully.

Shirin Neshat’s claim that magical realism as a system of communication “has become very Iranian,” fits seamlessly with a line from season one of the Netflix series, Narcos: “There’s a reason magical realism was born in Colombia.” In the Third World, magical realism and Third Cinema are just some of the frameworks we can use to tell our stories, to portray our condition, in all its beauty and suffering, all its vitality and terror and absurdity. It’s a tool we can use to scream into the abyss, into the seemingly infinite world of problems we face every single day, problems which are so bizarre and callous that they appear to be a result of occultic evils and bloodthirsty demons. Problems which nonetheless are a result of deliberate human actions.

Juju Stories is an anthology of tales we grew up hearing told back to us, this time identifying with us instead of merely being scary stories to tell in the dark, giving a voice to the infinite screams emanating from deep in our souls.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows with Google calendar.

Juju Sotires is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

2 Comments