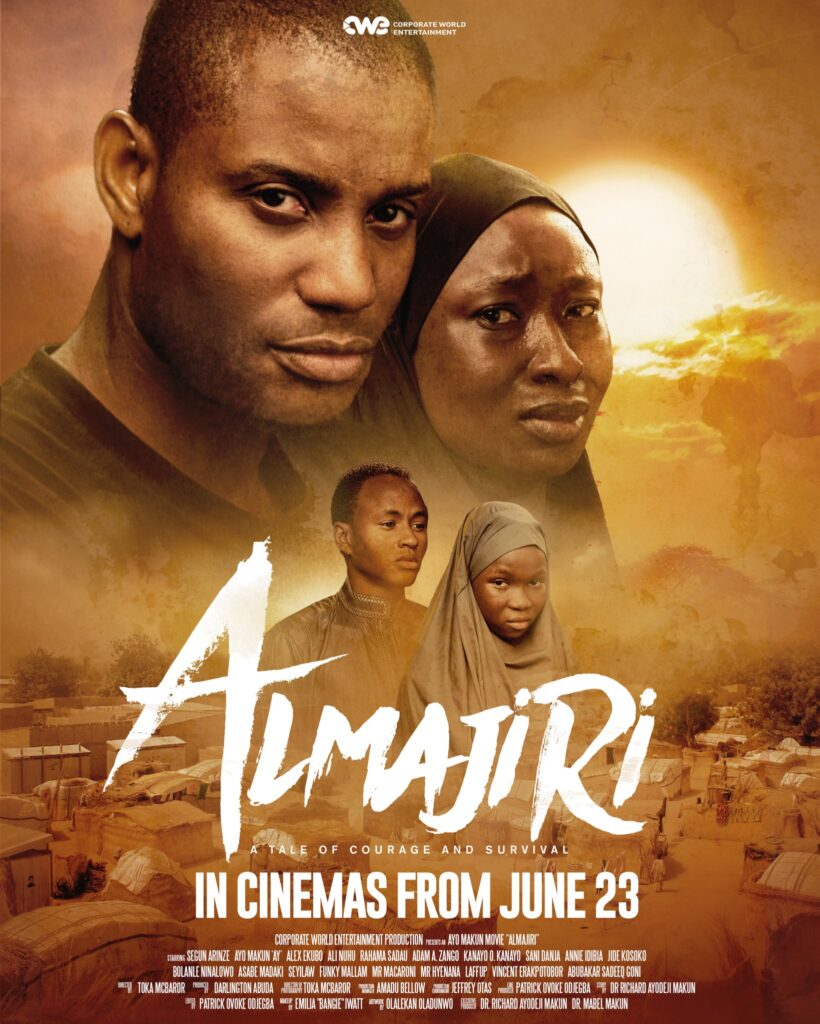

I never thought I’d say this: Almajiri is a better exposé on some of the heinous things that go bump in the country’s dark underbelly of violence and crime than Gangs of Lagos or Shanty Town. Both films feature a ton of senseless violence and death, a tragic and unmistakable part of Nigerian life. One thing they fail to do, however, is construct a compelling protagonist to lead the audience through it all. In Gangs of Lagos, it’s hard to be pulled into the orbit of Obalola’s desire for revenge and bloodshed because the loss of his dreams doesn’t seem to mean that much to him. And Shanty Town seemed more interested in overwhelming the audience with a grim and gritty atmosphere, than in telling a good story through compelling characters. Almajiri is a film with an important message that does not neglect to couch it all in a riveting story— a dark bildungsroman if there ever was one.

A ‘Dark October’ Essay: Linda Ikeji and the Mob

A ‘Dark October’ Essay: Linda Ikeji and the Mob

While, according to the film, the events depicted are inspired by real-life occurrences, they in no way represent the totality of the Almajiri experience. There is reason to wonder whether the title was chosen in a bid to sensationalize the information being passed across. A link to the history and nature of the Almajiri system has been provided in the side musings.

The story begins in medias res: a boy is being flogged mercilessly in a dimly lit room. Directed by Toka McBaror (Dark October), this grimness sets the tone for the film going forward. Even when nothing terrible seems to be happening on screen, we cannot shake off the feeling of something being off, like a constantly moving itch we cannot give a good scratch. We don’t know it yet but the first scene is set in an Almajiri camp in Lagos. There is an Alhaji (Segun Arinze) who runs the place. Our main character, Salihu Farouq (Alexx Ekubo), is his favorite. Like Gangs of Lagos’ Obalola, Salihu also guides us through the events of the film with a voiceover narration. The first thing he says is: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.”

In the next scene, we are introduced to a young Salihu and his best friend, Nafisat (Maryam Waziri), in their village located “somewhere in Northern Nigeria” called Angwan Zogole. Salihu is the star footballer and together with Nafisat, harbors hopes of leaving the village for Lagos in search of their fortune. The dream to go to Lagos is an option in the first place because of Alhaji Makarfi (Ali Nuhu), the great benefactor of the village; he arrives Angwan Zogole every now and then, riding on a steed like a king, and during his stay, picks some of the village children to go to Lagos under the auspices of his scholarship programme. Something about the whole arrangement doesn’t seem quite right, however, especially when he informs some villagers about the status of their children merely by showing them a picture; surely, a man rich enough to send a good number of students to institutions of higher learning can spring for a phone call. His whole altruistic schtick rubs me the wrong way, when, after addressing a crowd gathered outside his house, he flings naira notes at them and walks away. No one who has a shred of dignity and humility would do that.

In the scenes that follow, our fears are confirmed. Makarfi is nothing but a human trafficker, sending children to Lagos not to study, but to become part of his citywide network of Almajiri who venture into street begging, manual labour, and even sex slavery, becoming merchandise for sale to the highest bidder; these are undocumented citizens living at the fringes of society, reported missing by no one. It is said that you can tell a lot about the state of a country by the way it treats its lowest-class citizens: prisoners, the homeless, people living with one disability or another, the poor/destitute, at-risk children/youth, people with debilitating mental health conditions, and so on. Are there systems in place to protect them from coming to harm, from being exploited by monsters? It is very clear what the answer in Nigeria is. More often than not, it has to fall to NGOs to tend to the plight of the aforementioned groups of people, but even they can only do so much. Human trafficking (essentially modern slavery) is a wildfire raging across the globe, among developed and developing countries alike. Although it is impossible to determine the exact number of people trapped in this life, some estimates are as high as 50 million. According to the film, there are currently about 13.2 million Almajiri children in Nigeria, many of whom are at the mercy of criminals. One can only hope this film functions as a call to action for governments and organizations.

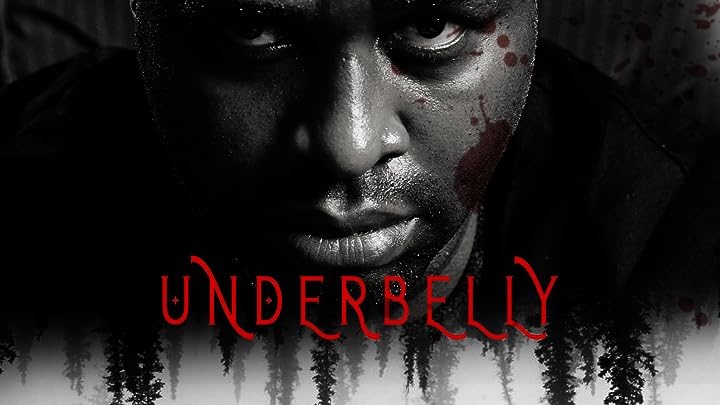

‘Underbelly’ Review: A Promising Period Drama with Unfulfilled Potential

‘Underbelly’ Review: A Promising Period Drama with Unfulfilled Potential

2018 Nollywood Films Available to Stream—The Year that Gave Us ‘King of Boys’

2018 Nollywood Films Available to Stream—The Year that Gave Us ‘King of Boys’

The directing and cinematography in Almajiri are brilliant in short bursts. It features a lot of the expected Nollywood trademarks, particularly superfluous drone shots. And yet, in a few dialogue scenes, like one between Salihu and the Alhaji where the latter’s face is shrouded in darkness, it shows the efficiency of its visual storytelling. The cast here is huge, and they bring varying degrees of authenticity to the portrayal of their characters. The standout is Segun Arinze as the Alhaji. Arinze is so good at displaying the Alhaji’s seemingly benevolent side that just for a moment, you forget that his character is a cold-hearted beast who wouldn’t hesitate to murder anyone who crosses him in cold blood. Alexx Ekubo brings a calm yet dogged demeanor to Salihu, and it works half the time. I don’t think I have ever not liked an Ali Nuhu performance.

Even though she gets limited screen time, Asabe Madaki will win your heart as the adult Nafisat. Her re-entry into the story will no doubt deepen your emotional investment as you wonder just how these evils can go on in our society unchecked. For the most part, the film works well; its pacing isn’t as smooth or crisp as The Trade, but I wasn’t too busy checking my watch wondering just how much story was left, so, that’s a good thing.

At some point in the story, Salihu says in his narration, “Every night, when I close my eyes, I see myself in my village”, an already heartbreaking line made even more so by the sincerity of Ekubo’s delivery. Halfway through, Almajiri veers into a subplot about Lagos gangs. These scenes are important, especially considering how they build to the climax of the story, but the film loses me for a bit here. Like Adam Sandler before him, AY, the comedian, casts himself and his friends as the members of the gang. Seyi Law shines, providing some much-needed comic relief. AY tries as Oloye, but his performance holds little sway in the story because he plays his character, a gang leader, as equal parts menacing and laid-back, an odd mixture which I didn’t find convincing. Bolanle Ninalowo (Far From Home) is here too, and so are Mr. Macaroni (Ayinla), Kanayo O. Kanayo (Living in Bondage), Jide Kosoko (All Na Vibes), and Annie Idibia, who has very few lines in the film. A Tuface song is used on the soundtrack, and this particular experience is even mentioned by Seyi Law’s character at some point. I couldn’t decide if this was jarring or a well-placed tongue-in-cheek moment.

The worst part of Almajiri is the climax. Like Soole before it, the story devolves into a shootout. Bullets fly. Stunt actors yell. What little fight choreography exists looks very much like fight choreography. There is haze everywhere, as well as shaky camerawork and headache-inducing editing choices. I couldn’t tell who was where or which side was gaining the upper hand for a while. They might have as well shown a card on screen with, “the two sides fight and stuff”, written in all caps. There is a way to build a drama or thriller into an action-inspired climax. Almajiri fails to find it.

The film’s ending is bittersweet, and might have you shedding a tear or two. I was the only one who had bought a ticket to see the film in my theater. I was a bit moved and impressed by the end, slow-clapping as the credits rolled. Almajiri is not a home run by any chance, but it manages to hit the ball quite far indeed, and more often than not, that is enough.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- The young actors no doubt give their best but Abubakar Sadeeq who plays young Salihu gives a better performance.

- I cannot overstate how effective Seyi Law’s character is at being the comic relief.

- I cringed at the “Hausa in Lagos?” line, as well as a couple others. The film could have handled this tastefully but it didn’t. Hausas in Lagos should never be an issue. Neither should Igbo people in Kano. Or Yorubas in Port Harcourt. Human trafficking (and the system that allows it to thrive in the first place) is the problem here.

- There is a subplot about a man who brainwashes children into becoming suicide bombers. He promises them that after committing the deed, they’d open their eyes in paradise. These scenes hit home because real-world examples abound, of people who, in spite of their education, hold on to deadly cultural/religious beliefs. Imagine how much more children can be manipulated when they are deliberately refused an education, a fundamental human right. When you keep people poor and uneducated, you can hold them under your thumb forever; this is the philosophy of Alhaji Makarfi and his real-world counterparts. This is how they’re able to hide under the cover of darkness, pulling puppet strings.

- Further reading on the Almajiri system.

2 Comments