In 2019, the number of Nigerian students in the United Kingdom was 1,586. By 2022, that number had skyrocketed to 51,648– a whopping 3,156.5 percent increase– and that figure shows no signs of slowing down. To say that there is a ‘japa’ wave currently sweeping across the nation, and indeed the continent, is to understate matters– it’s more like a tsunami. Last year, the Nigerian Immigration Service called it a ‘worrisome phenomenon,’ with good reason; the rate of emigration of everyone from skilled workers to students is undoubtedly alarming.

‘The Way Things Happen’ Review: “Cinema as Therapy”

‘The Way Things Happen’ Review: “Cinema as Therapy”

Apart from the economic downsides and other macro problems that come with this mass flight (for instance, in some states, the doctor to patient ratio is a mind-boggling 1:30,000), there are severe implications on a much smaller scale, for families, lovers, friends, business partners, etc. Many Nigerians can bear witness to the sudden disappearance of certain people from their neighborhoods, schools, offices, and places of worship, only to hear a while later that “so-and-so is now in Toronto/Kent/Copenhagen/Rijeka/Johannesburg/Paris/Mexico City.”

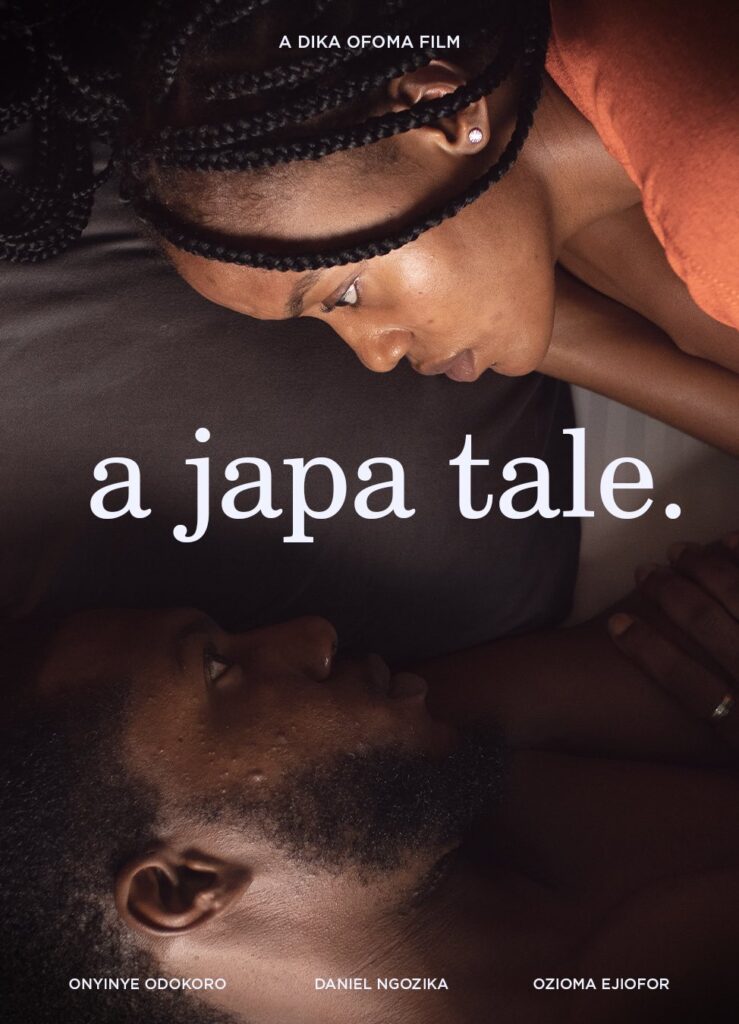

How this situation affects couples, those yet to be married and the ones with children, has been the subject of many a Twitter thread, with different people sharing experiences, hot takes, and pieces of advice with varying degrees of usefulness, on the platform. In 2021, the Esiri brothers’ drama Eyimofe centered on three characters planning to, against all odds, flee this country’s shores without so much as a backward glance for old times’ sake. Taking a page out of the films of the Taiwanese New Wave, the directors managed to capture, in detail, the desperation and latent hopelessness driving the characters to pursue their goal of relocating abroad; for them, home has offered nothing but disappointment– leaving is a last resort, the tiniest ray of light at the end of a long, dark tunnel. Because of this, the audience can easily understand their motivation and identify with them. A Japa Tale, Dika Ofoma’s latest short film, unlike Eyimofe, is less about the unfavorable conditions that cause people to abandon their fatherland for greener pastures abroad, and more about the strain that the reality of emigration puts on a relationship; however, it would have benefited from giving us more insight into the former.

Emuche (Onyinye Odokoro) and Dubem (Daniel Ngozika) are two young people deeply in love with each other; the very first scene tells us this much. Immediately they wake up, the couple begins to banter, in a manner more common among old friends turned lovers. This three-and-a-half-minute scene wastes no time going about its purpose, which is to introduce the audience to the ‘normal world’ of the characters. The first sign of trouble comes when Dubem’s mother, played by the always-brilliant Ozioma Ejofor, during an awkward lunch, has a skirmish with Emuche, the clashing of their very different personalities louder (and more grating) than the clang of cutlery against ceramic. When the couple is alone, an offended Emuche tells Dubem that she wants to call it quits: “I don’t want to do this thing anymore…Let’s break up.”

Because the story is told non-linearly, the moment that follows that very sentence is a flashback to Dubem and Emuche doing the dishes. Unceremoniously, Dubem tells Emuche of his upcoming trip to Manchester, “for my PLAB 2 exams.” He tries to sell her on it: “I’ll FaceTime you everyday…there’s no long distance relationship in our virtual world.” Emuche’s reply is simple and short; “Shut up,” she says, justifiably. I wanted Dubem to keep quiet too. His delivery is flat, almost deliberately passive, and if not, then painfully oblivious. Emuche continues to ask him to shut up and Dubem keeps pleading his case like a bored, underpaid defense attorney. The scene ends with the following exchange. “We can work this out,” Dubem says. “We?” Emuche responds. “We ended the moment you paid for IELTS and let me go on dreaming about twins named Chiamaka and Nwamaka.” And with that, she storms off. It was at this very moment I noticed I didn’t care about the relationship on screen. Not as much as I’d have liked to.

‘Gasper’ Short Film Review: Portrait of a Man in Trouble

‘Gasper’ Short Film Review: Portrait of a Man in Trouble

First Look: Winifred Iguwa Unveils First Teaser for ‘9TH FLOOR’, Sci-Fi Thriller Short Film

First Look: Winifred Iguwa Unveils First Teaser for ‘9TH FLOOR’, Sci-Fi Thriller Short Film

Another flashback informs us that Emuche is pregnant. Upon finding out, Dubem decides to marry her (“I will let my people see your people…nothing elaborate yet) and have her stay with his mother through her pregnancy until they come up with a better arrangement. In the present day, the couple is still quarreling and we are finally treated to the reason Dubem is trying to leave the country: “I am a doctor who hasn’t been paid in nine months.” Emuche’s decision to stay behind in Nigeria is also revealed: “No, I don’t want to go to the UK. I’m fine here. My dreams are here. Nollywood is here.” Dubem’s mother interrupts the session to drop some hard truths on them; Dubem is going to the UK and that’s final. After a brief montage showing the couple in love, they part ways. For good? Probably. Probably not. The film ends, without much opportunity to explore the conflict it sets up.

The story is supposed to be about the effect that japa-ing (or at least, the need to japa) has on their relationship, but the film seems not to know how to delve into those deep waters, content to stick to the shallows, thus doing itself and the audience no favors. Dubem drops his plans on Emuche like a bomb. Before this, there hasn’t been any mention of this trip or the reason he desperately needs to write the PLAB 2 exams. The audience doesn’t see him struggle with the decision to tell Emuche either; as a matter of fact, we are given very little idea of the interiority of the characters. How can we empathize with his decision to leave and hers to stay behind if we are never shown why these are the paths they have each chosen? (It’d be like if Chazelle tried to make the audience care about Mia and Sebastian going their separate ways in La La Land (2017) without initially showing us just how passionate they are about acting and jazz respectively, and how far they’re willing to go to succeed in them). Dubem only mentions that he hasn’t been paid for 9 months after the audience becomes aware of his plans to travel, and even then, the actor delivers his lines facing away from the screen, to a disgruntled Emuche on the other side of the room. There is nothing wrong with ‘telling’ sometimes instead of ‘showing’, but the telling has to be done well.

In a review of Ofoma’s previous short, The Way Things Happen, I commended the decision to turn the “camera on the girlfriend’s face, sometimes in profile, sometimes in an uncomfortable close-up,” as a way to force us to reckon with her grief. It afforded the actor, Echelon Mbadiwe, ample opportunity to communicate the mood of the film to the audience, supported by the subdued camera movement and muted design of the world. Here, the actors are not given such freedom; there are very few close-ups in the film, and it always seems like the characters are being held at arm’s length.

This restrained, hyper-minimalist, almost-cold approach can work. It was used to roaring success by Ebuka Njoku in Yahoo+ (2022), and even in the Cate Blanchett powerhouse drama, TÁR (2022), from Todd Field. However, in A Japa Tale, the decision to ‘contain’ the various on-screen elements appears to work against audience investment.

From the very first scene, the audience is not effectively sold on the interaction between the lovers; again, not to make too many comparisons to the former film, but Mbadiwe and Chizuroke are more believable as a couple than Odokoro and Ngozika– I’m sure both of them are performers worth their salt, but there is something off about the delivery they bring to A Japa Tale. This disconnect between Ofoma’s script and the actors’ performance is the reason the emotional beats fail to land with grace.

And yet, there are more than a few things to like about this film. Ofoma’s dialogue remains simultaneously natural and lyrical, in the way he ensures that his characters flow seamlessly from English to Igbo. Even the clash between Emuche and Dubem’s mother is an opportunity to demonstrate that the people are far from a monolith, rich and diverse in many ways. Ozioma Ejifor shines as the no-nonsense matriarch who wants the best for her son, and is, like many people in that generation, unaccepting of many of the ways the youth today live their lives.

At the end of the day, A Japa Tale is a story we’re all too familiar with, delivered to the best of their efforts by a filmmaker, crew members and performers all trying to forge a new path for themselves in the industry by telling their own stories, and sometimes, that is enough.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Watch the short film below

6 Comments