There is a small café on the left-hand side of the fairly ordinary Palms Shopping Mall in Lekki. The jazz music is unremarkable and never quite at the right volume to be appreciated or ignored. The small coffee-sipping, croissant-munching patronage is doing its best to ignore the blandness of the music. The colours are olive green and wood.

If you walk through this establishment on any given weekend, you are liable to find Michael Gouken Omonua perched amiably on the seats that rest by the wall – his sizeable shifty glasses resting on his ears.

Also, he will be sipping coffee with the air of a connoisseur in nirvana though he’s “not even a coffee drinker to be honest.”

He welcomes me into the space opposite his and I get to asking him about something we have in common: Anime. His eyes light up and he takes me through his love for the artform – its effect on his childhood and his perception of art and the world around his childhood. This conversation segues into his childhood and he takes me through his childhood in the UK. “I was probably one of the last generations who were just allowed out on the streets.” I point out his upper-class British accent, far removed from the immigrant-sodden “streets” of North London in the 80s and 90s that he describes. Michael becomes serious and tells me that whilst he didn’t have Etonian education, he had what was second best: an education at a marginally less snotty affair down the road at Ascot.

6 ‘Juju Stories’ Easter Eggs and References You Might Have Missed

6 ‘Juju Stories’ Easter Eggs and References You Might Have Missed

I think about the man seated opposite me and his posh private school dorms and the Chinese, Japanese, Russian kids that filled all its rooms with their video games and mangas and cultures. I think of him hunched over a line of film in some dark room after working fast-food to fund an education at University for the Creative Arts at Farnham, and I chuckle. It is a distant cry from where he’s cut his teeth. Writing and filming stories so Nigerian, you could be forgiven for thinking he’d never lived amongst other people or spoken any languages not forged by the Niger or Benue.

Take his time-manipulating 2018 short Loop Count. The film is riddled with uncomfortable repeated and mumbled shots of a married woman and her paramour. Superimposed on the action is an audio of a woman, presumably our wandering wife pouring her feelings of lust and guilt to a faceless woman over the phone. The conversation oscillates from one emotionless question from the faceless woman to answers drawn out painfully from our protagonist’s voice thick with lust and guilt and uncertainty as she relates her feelings. All of this happens in real time and in the past, the future and some time-space left to the imagination. The action is seamless as it segues from one slightly erotic syllable into another but it is not simple. Never that. For all its near-masterful toying with time, though, Loop Count’s biggest draw was that it did everything it did with its word exclusively in Pidgin or Pidgin English, the distinctly Nigerian corruption of the English language that Omonua heavily favours in his films. And perhaps this is Omonua’s biggest claim to understanding Nigeria and its most impressive problem: coherence or a lack of it. “It’s a pretty commonplace language (in Nigeria)”. I agree. It might be the only really commonplace language in the country. The country has existed for a hundred and eight years yet it seemed many times like a medieval hell-scape of feuding fiefdoms with distinct grouses, opposing heroes and diverse unintelligible modes of communication. He continues talking about Pidgin. “It has sort of been relegated to this second-class thing. I think Pidgin has a poetry to it.” He however hopes to make movies that make use of a diverse number of languages. “My new film is actually predominantly English just because of who the characters are.” I nod my head. Pidgin can only offer so much poetry for a mind bent on writing a lifetime of verses.

I always feel like it’s important for filmmakers to cultivate a voice. The problem with the Nigerian industry at the moment is that it’s not encouraged. You often can’t distinguish between one filmmaker and the other.

Michael Omonua

But Nigeria has other features beyond incoherence or potential. In a country that offers little by way of justification for anything, people have to find their faith somewhere and everywhere. The church fulfills both caveats. It is somewhere and everywhere. An unwavering cathedral of song, penance, grace, of course, theatre. See, Omonua understands this theatre better than many despite spending his formative years away from its strongest soldiers. This ritual of worshipping, praying, miracle-ing requires just as much dedication to its practice as it does the process that ensures that the practice, the show, the performance goes and goes on.

I watched Rehearsal (2021) on the recommendations of a friend earlier this year in all blue-ish glory, and I still recall how I felt upon completing it. Like I had completed something worthwhile. Rarely in our race to degeneracy via rabid media consumption do we modern humans understand just how transformative said media could be or is. We just consume. But I understood what I had just watched. I understood at least the import of the affair. I understood the story almost by the most striking of instinctive impulses – the kind that is reinforced by the steel of familiarity, time after time.

The story snakes its way through a factory of faith – a manufacturing hub for the myth of divinity in Nigeria. Auditions, rehearsals and everything in between as undertaken by the man in charge (played by Richard Brutus) and members of his spooked and spooky “flock” create a distinctly uncomfortable feast for your eyes. As with any hall of religious authority in a place starving for supernatural answers like contemporary Nigeria, questions of authenticity rise as constantly as poverty does. And the religious gatekeepers answer all questions by deciding who asks. By deciding whose prayers are answered or seem answered. It is a perfect system except for the abuse – often violent and the deceit underpinning it. And it never ends. With Rehearsal, Omonua explores a self-reproducing concept in a stoic long-shot format whose scenes seem like natural successors to a story we’ve all heard before, seen before, suffered before, yet do not really understand.

Movie Review: ‘Juju Stories’ is an Occultic Rhapsody

Movie Review: ‘Juju Stories’ is an Occultic Rhapsody

As for understanding, Omonua admits that his style might not necessarily brook an explicit absorption of the work. “For me, the perfect film is when you blend a conceptual idea with narrative and then, you complement the two”. Is that his style, then? Stacking supra-super narratives on each other like some monster from the comics? Yes? No? “I always feel like it’s for others to dictate that, but it’s always been asking myself ‘Who am I?’. You start by cloning someone else, of course”. Who did he clone in those early days? He produces some names. Paul Thomas Anderson. Christopher Nolan. Soderbergh. “And then you try to find interest in conceptual ideas and different ways to tell stories.” For him, style is not some ‘ism’ tucked somewhere in the textbooks at film school or a pretension to having great answers. It is instead the ever-changing result of a process marked by interaction with and a distinguishing of the self.

Omonua is no stranger to critical acclaim. Born (2016) and Brood (2017) made it to “Beyond Nollywood”, Nadia Denton’s 2018 slice of the International Film Fest Rotterdam and Loop Count was screened in the same year at the British Film Institute, but since its release, Rehearsal has heralded Omonua into a level of critical acclaim locally and internationally that eclipses all preceding acclaim. Spots and accolades at the uber prestigious Berlinale, a prize for Best International Short Film at the Kurzfilmtage Winterthur (one of six Oscar-qualifying destinations the film will go to), a selection at the Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival and the Chicago International Film Fest are just a few of the very high notes the film has hit in its public run.

The acclaim is not just limited to legacy corners of the film world as festivals are, but has made its way to the popular psyche. Earlier this year, Rehearsal was named as one of Vimeo staff picks and was King for a week in its shorts category. I wonder why Rehearsal has resonated with audiences, especially of the foreign variety as well as it had. I suggest it might be because of its capable director. Omonua welcomes the praise. “I’ve worked really hard on my craft. A lot of people don’t know about me and that’s because I’ve been focusing on craft all these years. Learning. Studying. Working on low budgets and scales while focusing on my craft. With Rehearsal, I thought to myself ‘I need to scale up. I need to get as much production value as I can’.”. Again, he alludes to the meta narrative(s) at play in his work. “For me, the strongest part of Rehearsal is the meta narrative where the story at times works on two separate levels.” In the end, though, he thinks it might all have come down to a timely shifting of tastes in the wider world of film towards Nigeria. “There’s something about film set in Nigeria that’s based around religion in an interesting way that’s resonating internationally. There’s a Nigerian film by Akinola Davies that won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 2021. It’s called Lizard.” I frantically search my memory for Akinola Davies as he exhausts a short list of Nigerian films of that ilk that have gotten international success. I appreciate the veracity of his submission, but I express that I think Rehearsal has more standalone merit than he is willing to accept. The self-awareness isn’t too unwelcome at any rate.

Every discussion of a foreign place must end on the current place. On the film of Lekki and Abeokuta and Asaba and Sabon Gari, and I didn’t intend on exempting this interview from that ragged and illustrious thread. So, with one eye on emptying the remarkably tasteless sugar dust into the incredibly bitter cappuccino— which I drank out of courtesy— I ask about Nollywood and its subpar storytelling. “Voice!”, he quips in response. “I always feel like it’s important for filmmakers to cultivate a voice. The problem with the Nigerian industry at the moment is that it’s not encouraged. You often can’t distinguish between one filmmaker and the other.” In keeping with the fashion of our interactions, I agree with him because I too have been subject to the frustrating sameness that Nollywood peddles as film despite the boundless stories to tell and ways to tell them.

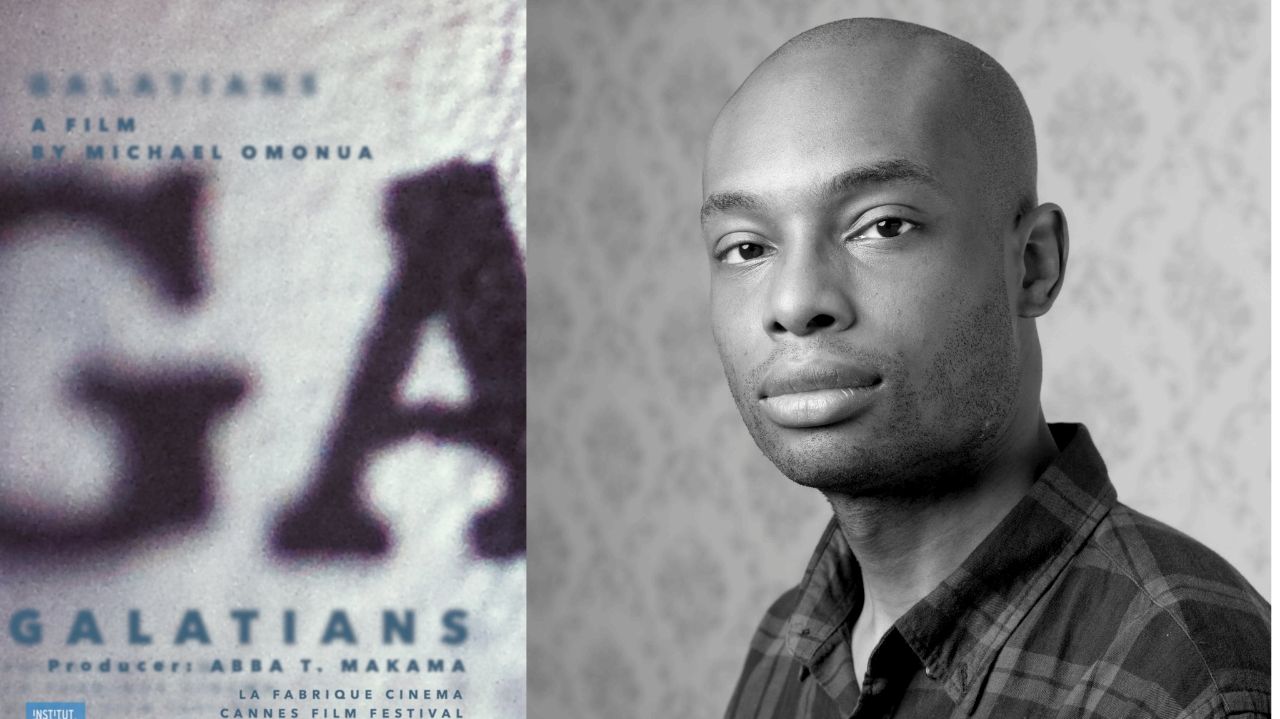

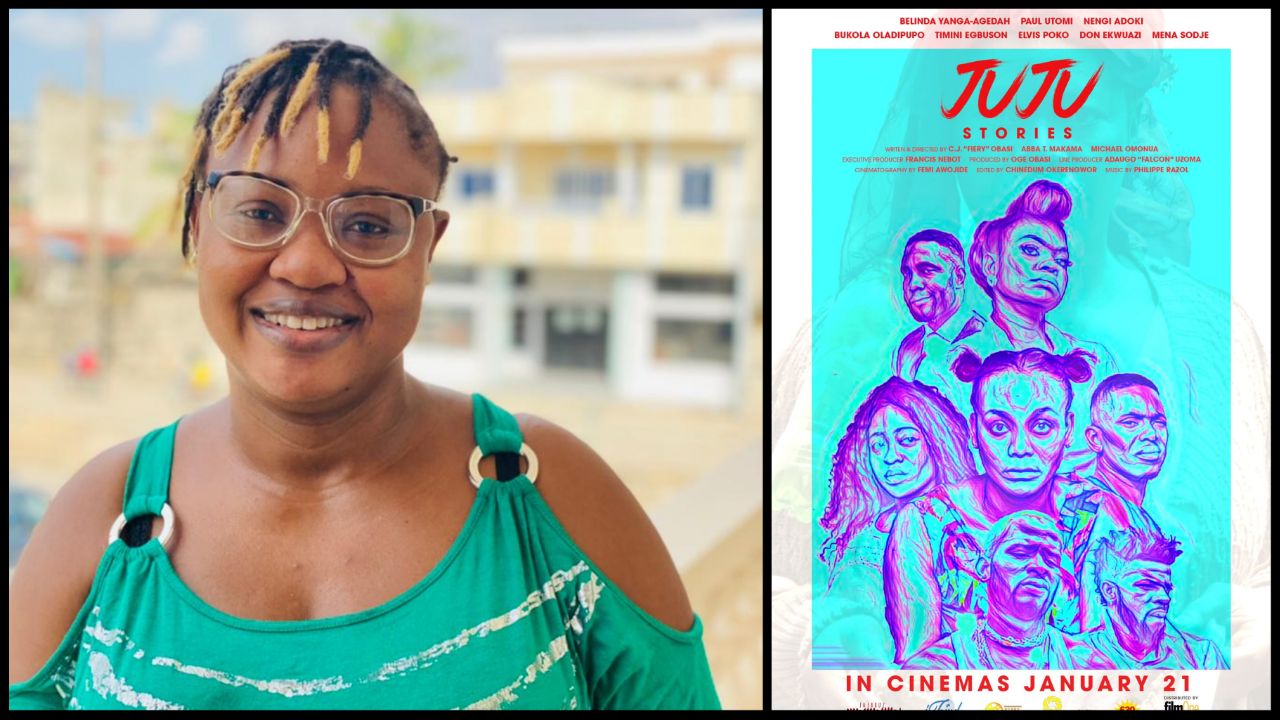

L-R: Michael Omonua, CJ ‘Fiery’ Obasi and Abba T. Makama

Maybe that’s a harsh and joyless summation. Well, here’s some more gloom for you. The manifesto of Surreal16, a collective of independent directors consisting Abba T. Makama, C.J. ‘Fiery’ Obasi and Omonua himself, does not allow for any stories or scenes centered around weddings. Much like their model film movement Dogme 95, founded by a Danish collective of directors who sought to rewrite the rules of Danish cinema and snatch it from uncinematic practices, Surreal16 has since its inception in 2016 sought to strip Nigerian cinema down to story and people – the core of all good motion pictures. Their manifesto at the least pretends to the cause. It is as anti-weddings as it is insistent on the use of Nigerian means of expression like Pidgin.

For all their peculiar airs, they’ve been doing good. Their horror anthology Juju Stories (2021) is probably the best horror film Nigeria has seen in a decade. A scare feast that interrogates as much of local lore as it can and presents its manifestations in daily modern life, Juju Stories is bound to excite any Nigerian film lover for any future projects from the bunch.

The coffee is finished now. And when things finish, we look to the new thing. Omonua is working on one. His website says he’s working on a new thing. A feature length called Galatians that will “(be) a continuation of Michael Omonua’s exploration of the Nigerian Pentecostal church system. Where the short focused primarily on rehearsals for staged miracles, the feature will see us explore many aspects of the church and delve deeper into the lives of the individuals involved in the corruption.” The title screams ambition. Omonua nods that indeed, it does. “Right now, I am very much inspired by people who use limitations in their work… (Robert) Bresson, Hartley… What I’d like to do (in the future) is have some more kinetic camera usage… More kinetic, more steadicam, more dollies. I want to experiment with the dynamic blockings I’ve been studying.” I tell him I’ll watch it with all the technical finery it promises, but I don’t think he hears.

The conversation has now devolved into the any-everything of film to candid, almost brotherly advice on navigating the subject. I spend a considerable amount of time in this period just watching the massive library of film history and general nerdery that is his head just gob its way from classic to classic, American, Chinese, Russian, Japanese and Nigerian. He in a way represented what many influential sections of Nollywood and the broader Nigerian theatre and film space loathed: a confidence in ideas and the expressions of same. I can literally hear the sneers in the uniquely Nigerian or is it human cynicism in bare words? “He’s such a theory man. All talk, no do”. “Na oyinbo we go chop?”. “Who theory help?”, etc. But Omonua and those like him have risen and continue to rise above the general din. His work shines as a tribute to ideas and words and confidence in said ideas. They stand not entirely alone but fairly friendless and singular, but they stand. And the people will continue to notice.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

GIVEAWAY: WKMUp 2022 December Advent Giveaway.

10 Comments