EXCLUSIVE: Brotherhood, produced by Jade Osiberu’s Greoh Studios, has generated buzz among Nigerian cinemagoers since its theatrical release on September 23, with many more still looking forward to its post-theatrical debut on a streaming service. The well-choreographed action sequences and performances of the actors have been celebrated, which testify to the competence of the film’s director, Loukman Ali. He clearly deserves his flowers and, for this reason, I thought to have a chat with him about the project, his background and his influences.

Movie Review: ‘The Girl in the Yellow Jumper’ and Questions of Verisimilitude

Movie Review: ‘The Girl in the Yellow Jumper’ and Questions of Verisimilitude

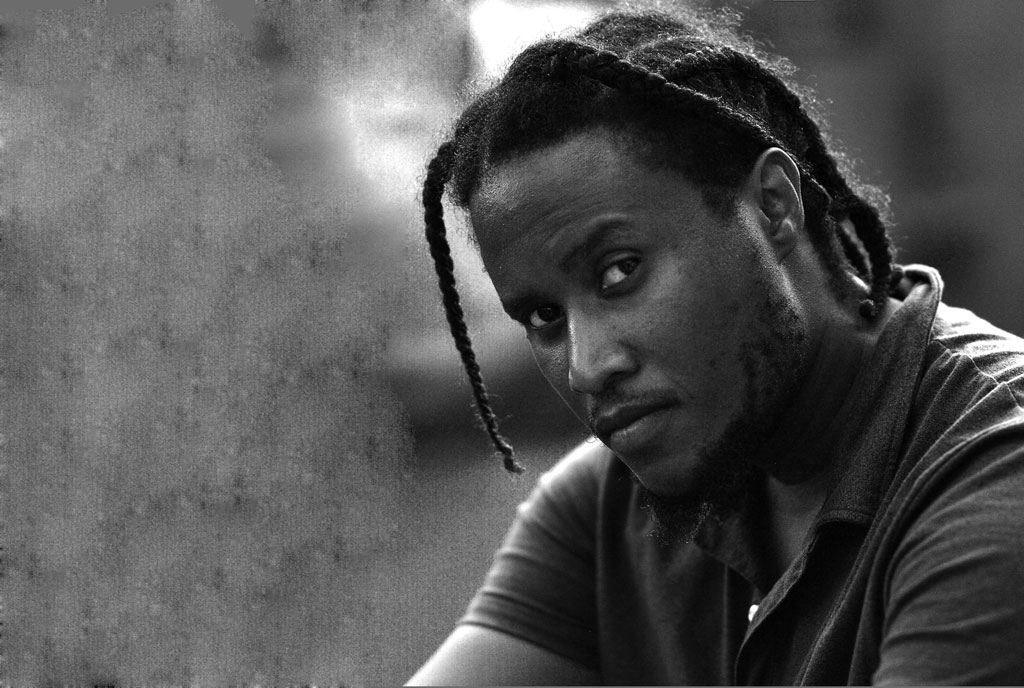

Ali is a Ugandan filmmaker popularly known for his film The Girl in the Yellow Jumper. What has caught my attention across his works is his distinct style and flair for action. Explaining the basis of his love for the action genre, the filmmaker shares “as a kid, I remember my passion was action films. I didn’t really care that much about drama or whatever. Right now, I actually have a lot more drama than action. I don’t know why everyone just sees the action. It is always a lot more than that.” He continues, “but for me, it has always been more interesting; the whole action. It’s these films that I watched that made me want to make films. I have watched romcoms, biopics and nice drama films. It’s the feeling I always get from nice action sequences that makes me want to be a part of this. It’s precisely why I do it. I do it because there’s a mini me out there that will see it and go, ‘Yeah, that’s what I want to do!’” His response also sheds light on his motivation for joining the action-filled Brotherhood project as director-cinematographer.

In a statement during the project’s announcement in April, Ali shared “I hope this film opens up doors for more partnerships between African filmmakers. This is the beginning of many firsts for African cinema. We are taking risks and hope to excel. The Nigerian audience and Africans at large should expect a Nollywood high stakes crime-action thriller like never before.” Shortly after, the filmmaker was joined by a pan-African production crew who flew into the country to deliver an African blockbuster like we have never seen in recent times.

“I think when I was working with Nigerian actors, they were more mastered than people from my country. Not like people from my country are not improving, but I felt like the actors in Nigeria seem to have a little bit more experience in acting. So, it was slightly easier to direct,” describes Ali as he looks back on his experience and time on a Nigerian set. “I think there is a bigger market in Nigeria and there is a lot more money to spend on film than in Uganda”, he adds, when asked about the differences between the film industries in both countries.

Anybody that has a conversation with Loukman will have no doubt that he is a brilliant and knowledgeable filmmaker who has been inspired by others. I proceed to ask him about some of the filmmakers that have influenced him the most. “It’s like asking a musician ‘Which musician inspires you?’ It’s a whole library. The major ones are Tarantino, James Cameron, Steven Spielberg and Edgar Wright. When it comes to African films, I am probably more familiar with films than the filmmakers themselves, because African films are only becoming accessible now.”

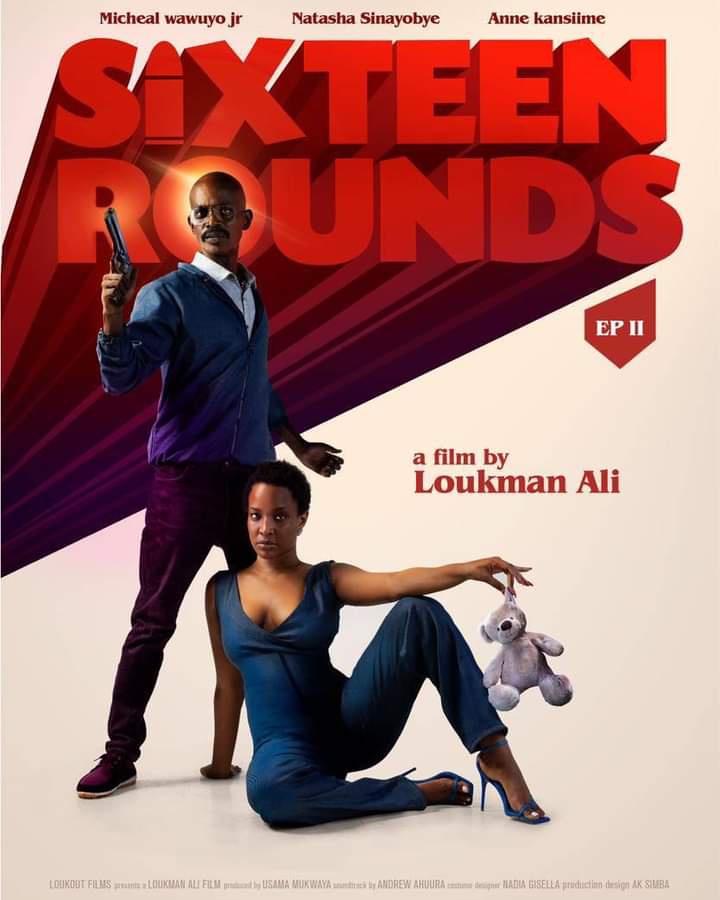

It was little surprise to hear Quentin Tarantino’s name, as the American filmmaker makes use of violence and action in his films, elements that can also be observed in Ali’s projects. A striking similarity I find between Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds and Loukman Ali’s Sixteen Rounds lies in the usage of camera movements to reveal information. In the former, the camera tilts down in a scene to reveal a Jewish family hiding underneath the floor. Set in the Holocaust era, the Jews in the film have to hide from Nazis to escape execution. In Ali’s work, the main character is exposed hiding underneath the bed from his cheating wife. He plans to murder his wife’s lover stealthily, the camera reveals.

An extension of Loukman’s ingenuity can be observed in his film titles. From The Girl in The Yellow Jumper which is the first Ugandan film on Netflix to Sixteen Rounds which won the best African short at The Durban International Film Festival this year, he clearly knows how to catch an audience’s attention. On the inspiration behind titling Sixteen Rounds, he responds: “I used to work in advertisement, so I am well aware that sex sells here in my country. I knew that a lot of people would think the film is about something else, which would help me get the word out there. Originally, it was supposed to be ‘Twelve Rounds’, but there are so many films with that title. So, I figured, ‘What’s the most I can hold in a 9mm magazine?’ There are guns that can hold seventeen rounds, and if you lose one, you would be left with sixteen rounds at the end. That’s kind of where the idea came from.”

Loukman Ali’s creativity extends to other forms of art and it is no news that he used to be a graphic designer. He reveals that he designs his film posters himself. “During the writing, I’m thinking, ‘How do I express this idea in a poster without being too obvious? It’s the graphic designer and advertiser in me that helps me express these ideas in a way that pops”.

On if he thinks every filmmaker should learn an art form first before they make films. He replies, “I mean it’s important you learn something art-related first. You don’t have to, but it helps”. One would think that as a result of his art background, he makes use of a lot of symbolism in his films. For instance, a gas mask is used in two of his films: The Girl in The Yellow Jumper and Sixteen Rounds. However, he explains, “in school, I used to draw images and people would ask me, “What is the meaning?”, and I would always laugh because it would mean nothing. It was just an image that was available when I was bored and I drew it. I did not really have a deeper philosophical reason for doing it. So, in regards to the mask, I used it in The Girl in The Yellow Jumper because one of the actresses didn’t show up, and then, we had to shoot. So, we got a double and used the mask because it was available. With Sixteen Rounds, the character was a soldier, so one could say he had his mask lying around. Since we had an old mask, we just used it. In regards to philosophical reasons, I absolutely have none. I just put things together.”

Like many independent African filmmakers, Loukman Ali has proven his depth. We went further to discuss culture in film, and as expected, his take on the subject was far from asinine or generic. Brotherhood is a Nigerian film, so one can’t help but wonder how the film would be affected by the cultural background of a non-Nigerian director. “I tried not to put in a lot of cultural things from my side because I didn’t really see the need. It had to stay a Nollywood film because it is a Nollywood film. I tried to concentrate on making things better, in whichever way I could. Even at home, I don’t really do much culture-wise. I feel like Nigerians are a little bit more cultural than us. We don’t have a very strong culture. We just have so many things mixed together that we don’t really know who we are”.

The Maverick Auteur: The Life and Films of Tunde Kelani — A Breakdown

The Maverick Auteur: The Life and Films of Tunde Kelani — A Breakdown

The depth of his responses gave room for a more extensive conversation that covers streaming services, African stories and the global perception of African films.

I never really entered this industry to be that guy who makes movies that make the most money. I have no interest in that. I just want to make a movie that I’m happy with, and people like myself are happy with and would inspire someone to want to make movies. That’s enough for me. I don’t mind the money when it comes, though.

You said you’re not so cultural in your films. Don’t you think that now that streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video are serious about Africa, we should show more of our culture?

I get that, but I want to be truthful in my stories. There are things with culture that I have not yet experienced. So, in my films, I show things that I have personally experienced like small cultural nuances. There is an Africa that the West expects, and sometimes, it’s not really true. Sometimes I watch this Africa and I can’t relate to it because that’s not the Africa that I know, and it’s not my fault that I grew up in a world where Africa is not really that different. You’re not going to watch an African film and we are wearing rags and no shoes. Of course, we’re going to wear shoes like everyone wears them but because we can’t afford some things, we have changed them to be something else and it is what people see and call our culture. It’s not because we want it to be like that. It is only because we have no other way.

I try to have some culture. I guess by having my people in my film, it’s culture already. The people are the culture. I’m not really concerned about “it needs to be African”. When I look outside my window, what I see is what I shoot. That is Africa already. I don’t really mind if someone in the US is watching and goes, “What am I watching? Cars?”. If you want to watch something else, then watch something else. What I have is what I have. I can’t just make up stuff because it is the expectation. This is why I have always had issues getting funding for my films, and I have always funded my films myself because I don’t like the idea of someone telling me my reality or what my truth should be. When they start talking like that, I’m always like “Never mind, I’ll do it myself”.

It’s not always necessarily about the setting. What about telling African stories in African languages? Do you consider making more of the dialogues in your film in African languages?

I feel like films set in old eras require this because the setting is from a time when most people didn’t speak English. But if I was to make a film set today, it has to be English because that is how most people communicate here. Most people speak English because we have many languages, and I don’t know the language of the North, West or East. So, when I meet these people, we tend to connect easily because everyone studies English. So, you find that I have been programmed to speak English, and it is the default language when I meet somebody else. I can’t assume that they speak another language. Some people even get offended that I assume that they are from another tribe.

Because of these issues, you ask yourself, “What can I do?”. I was born and brought up in a world where this is the language imposed on me and I see people have come from countries that have a single language like Korea. They might look at this and be like “oh” because some of them assume that in Africa, we speak one language. I was in Europe one time and someone would be speaking Igbo, and a white friend would ask me, “What are they saying?” I don’t understand a single word of Igbo, but to them, we all sound the same. So sometimes, they ask these questions out of ignorance. I‘m African, and even I used to think that in Nigeria, the people spoke one language. In Uganda, we have 52 tribes. If I made a movie out of just one language, then it might be only for that audience. Some people are not really keen on reading subtitles. I don’t like subtitles, so I don’t want to impose them. I’ll rather choose the language that cuts across as many people as possible.

I have always made films for people like myself. When I make my films, I first take them home to my family. We grew up watching films, so that’s my very first audience. I have to think about things like “would I watch this with my mom? Would I be comfortable watching this with my dad? Would this make them happy? Would this make us happy as a group?”. That’s the audience. If these people like myself are happy with it, I don’t really care if it is getting a billion. I never really entered this industry to be that guy who makes movies that make the most money. I have no interest in that. I just want to make a movie that I’m happy with, and people like myself are happy with and would inspire someone to want to make movies. That’s enough for me. I don’t mind the money when it comes, though.

What is the role of collaboration in taking African stories to the world?

There was something I was trying to do with Nollywood sometime back, but I think streamers look at numbers more than the quality of content sometimes which might not be a good thing in the long run. Most times, you go to a streaming platform and find so much, but there’s so little. You almost can’t find anything to watch. Sometimes, these streamers and other people don’t want to collaborate with a market because it is tiny although there might be good quality stories in that market that can’t be found in a larger market. I feel like some markets need to be given a chance because there’s a lot out there that they’re not seeing. When I came to Nigeria for the first time, my vision of Nigeria was from the times I used to watch old Nollywood films, so I was shocked at the quality of the production that I saw. I was sincerely impressed; I was like “Wow, all this time, we didn’t hear about this?”. The good thing about streamers now is that it is easy to access some films now. In regards to collaboration, I think streamers are the way to go now.

What’s your take on African stories being told by the Western world? Or it doesn’t matter who is doing the telling, as long as African stories are told?

I think it matters. Imagine if Spielberg was telling a story about Fela Kuti. The West might have read about his mom’s death or something, but they don’t know what it felt like to be Nigerian at that time. There is so much they can’t relate to. When you ask someone from the West, “Do you know what it feels like to comb your hair when it is dry?”, a white person can only imagine, but I can relate to it because I have African hair and I can tell what it feels like. If I am telling that story, I will have more empathy towards that subject because I can relate to it personally. As much as they can do a pretty good job telling that story, I just don’t think they should be the ones telling the story. I feel like Africans are in a better position to tell these stories.

Do you think actors who have not experienced Africa can fully embody African characters while telling African stories, as is the case in The Woman King?

That’s a bit controversial. I feel like the job of an actor is to act. I mean, you can act as an alien from mars. You don’t have to have been there to act it. But again, I see why it is important for a deaf person to act as a deaf person. Other people can only imagine what it feels like, but they don’t really understand. There’s just that thing you can’t really relate to or empathize with because you have never experienced it. For some of these people that have lived their lives abroad, I don’t think they can do a good enough job in my opinion. But again, they are actors. Who knows? Many actors do good jobs.

Loukman Ali is here to stay. He is putting in the work. Earlier this year, he was one of the winners of the Netflix-UNESCO African Folktales, Reimagined Short Film Competition that will see his funded short film premiere on Netflix under ‘An Anthology of African Folktales’. As a filmmaker who has trained himself as a screenwriter, director and cinematographer, he has revealed that he is working on a tragic murder mystery soon, “Like Murder on The Orient Express kind of thing. I’m very interested in that kind of stuff”. There is an acuity to his cinephile mind, that adequately sets him up to be one of the many African filmmakers that will be at the forefront of quality storytelling for Africans first, and then for the awakened global audience.

The Girl in the Yellow Jumper is streaming on Netflix.

Share your thoughts in the comments section or on our social media accounts.

Sign up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows with Google calendar.

Go fancy 👏🥂

Well-done Fancy!

Fancy! Give them!

Fancy my superstar Friend and Director 🙌🙌🙌🙌

Enjoyed this interview.