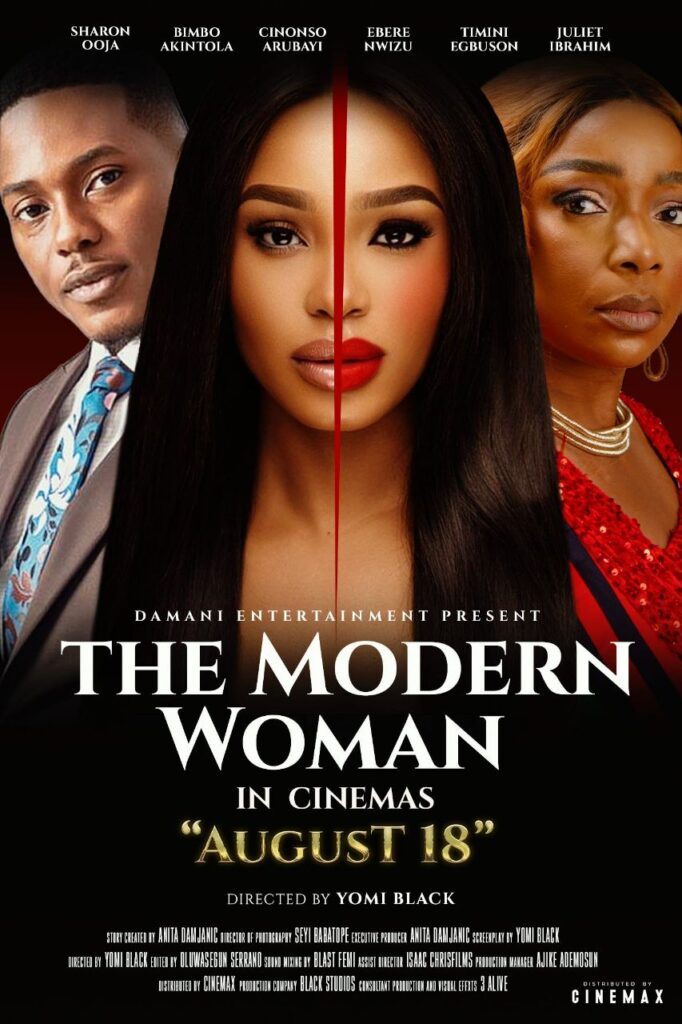

At no point during The Modern Woman was I the least bit moved by anything happening on screen. At no point were things kicked into high gear, causing me to inch forward in my seat, enthralled by the events unfolding. At no point was all the tension in the atmosphere defused by an expertly-timed moment of comic relief. When it ended, I did not clap (which I did at the end of Juju Stories, and The Trade), did not leave with a smile on my face (Ile Owo), and did not feel like I’d just had a good time at the movies (a feeling so basic, a film has to be truly unimpressive to pull such a feat). What we get in The Modern Woman is an assortment of the generic: from the characters to the story beats to the middling performances, all of which are applied in this project with minimum effort to make any aspects stand out.

‘Barbie’ Review: Margot Robbie Shines as Titular Doll but the Film’s Clunky Writing Casts a Shadow

‘Barbie’ Review: Margot Robbie Shines as Titular Doll but the Film’s Clunky Writing Casts a Shadow

The updated logline (after an initial controversy) reads, “A young woman’s carefully balanced life, torn between career, family, and love, spirals into chaos when she faces the devastating loss of her pregnancy. In a fight to reclaim her identity, she must navigate a treacherous path towards self-discovery, challenging societal norms, and embracing her own truth.” Sharon Ooja is our main character, Jennifer, married to Timini Egbuson’s Ron. After suffering a miscarriage, a traumatic and draining experience, her mental health takes a hit. Lying on a hospital bed, her face a waterfall of tears, she says to Ron, some variation of, “I know you’ve always wanted a family. I’m sorry I couldn’t give that to you.”

I think this was the first thing that clued me to something being off about the story. Why does she sound like she’s doing him a favor? Doesn’t she also want children? Why is she more upset that she has ‘disappointed’ her husband than she is about the physical and emotional toll the loss of the pregnancy is taking on her? Granted, Ron is gentle, reassuring her everything will be fine (as opposed to her mother who remains frigid and judgemental) but the film on a subtextual level wants us to praise him for not acting differently. It says, “Look at how calm and responsible this man behaves, even while his wife apologizes for not being able to grant him his one desire.” As if what we’re seeing is not the barest of bare minimums. As if she should be apologizing for ‘disappointing’ him in the first place.

We are introduced to other characters, such as our main character’s mum, Keke Kehinde (Bimbo Akintola), and her grandmother. The former is a stoic boss lady who, according to her daughter, ‘always gets what she wants’, while the latter is a caricature of an old, traditional woman, in that she cajoles Ron into drinking agbo in one scene after pestering him about grandchildren and getting a maid to help around the home. The maid, Lucy, (Nene Nwanyo), eventually joins the household and is only there to further drive a wedge between husband and wife. There is a moment at breakfast when Ron seems to be warming up to Lucy, complimenting her pancakes as the best he’s ever tasted. Jennifer offers no rebuttal, playful or otherwise, instead choosing to seethe in silence. We also eventually meet two of her friends who, when she is having problems with Ron, introduce her to a feminist association.

In the first meeting that Jennifer attends, the moderator notes that feminism is not about hating men, a banal line of dialogue if I’ve ever heard one. It is banal because even though it is said at a meeting of feminists (who should already know that misandry and feminism are not the same), it is clearly an attempt by the screenwriter to discredit the movement. That would be like if in a film set during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, a meeting of activists opened with a moderator telling everyone present, “Now, we need to realize that fighting for our rights is not the same as hating white people.” That kind of statement is loaded with the presupposition that a lot of the former has been mistaken for the latter, an argument that would most likely be made by someone looking to muddy the waters of discourse.

Now, are there some women who under the guise of feminism have nothing but hatred for every individual man they meet? Definitely. Haven’t you met the human race? We have all types of people. However, to have the moderator of a feminist meeting in your film immediately try to distance herself from misandrists implies that a large percentage of women in the real world fall under this umbrella, a sentiment that is laughable and untrue. I mean, women are angry for a reason. For a myriad of valid and very real reasons. The thesis of this film seems to suggest that a good majority of them are merely crying wolf, or jumping on a bandwagon with other haters of men to decry ‘the patriarchy’. I could write a whole essay on the above scene alone, but this seems like a good place to pump the brakes for now.

This ‘toxic feminism’ that the writer-director is so hell-bent on exposing comes to a head when one of Jennifer’s friends, a self-proclaimed feminist who has been bad-mouthing modern men and the institution of marriage every time she’s been on screen, is revealed to be getting married soon. Jennifer feels betrayed that her friend was trying to get her to ruin things with Ron, all the while chasing her own happiness. I should also mention that the reason Keke Kehinde is impassive is because she was done dirty by a man in her past.

‘Glamour Girls’ Review: Nollywood Classic Remake Falls Short of the Glitz

‘Glamour Girls’ Review: Nollywood Classic Remake Falls Short of the Glitz

Through these characters, the director manages to, in a grand display of obliviousness, misrepresent the idea and legacy of feminism and why many women today (whether married or single, young or old, wealthy or underprivileged) clamor to expose misogynistic practices and laws, and seek justice for the oppressed. To the filmmakers, the length and breadth of modern feminism is probably one of the issues mentioned in the film, “Why should I be the designated cook for my husband?” or something of the sort. Not that there isn’t a necessary conversation to be had about cooking (because women have lost their lives for refusing to do it) but the film brings up issues like who should cook in the home and a woman’s (lack of) fulfillment in her career, and then, through Jennifer, dismisses them with a wave as instances of feminists acting out, seeing Kilimanjaros where there are anthills.

One day, Ron comes home drunk and is hurling his guts out in the bathroom. Lucy, the maid, finds him and helps him up. He is still delirious (and most likely hasn’t washed his mouth of vomit) when she tries to kiss him. He pulls away at first, but she persists, leading him to the bed. Jennifer comes home at that moment and is mortified at the sight. Lucy runs away. Jennifer leaves. A devastated Ron cries in the rain. Heartbroken, Jennifer goes to meet her mum at her office. Keke Kehinde is with her friend (played by Juliet Ibrahim) when Jennifer enters. Her mum says to her, “Jennifer, you know tears don’t move me. I deal with words,” the latest in a long list of examples of tell-don’t-show screenwriting. Jennifer mentions that she caught Ron with their maid. Keke Kehinde is unmoved. However, her mum’s friend tells Jennifer that Ron isn’t like that. She tells her about how she attempted to get him to sleep with her but he ran away. This convinces Jennifer that there might be more to what she saw with the maid. This is yet another instance of the bare minimum being praised as noble and aspirational, in a misguided film, lacking in self-awareness.

Even the title is very non-specific: The Modern Woman. Is this supposed to be a definitive portrayal of women today? Is that why the article ‘the’ was used instead of ‘a’? Is the director trying to make an all-encompassing statement about the life and times of all modern women? Isn’t that just severely short-sighted and all shades of wrong? How well would a film titled, The Modern Man, go down with audiences? There is so much disingenuousness in this project that one wonders why the story is being told at all.

The performances in Yomi Black’s The Modern Woman are as bland as they come. Sharon Ooja (Glamour Girls) proves once again that her acting chops, for now, cannot sustain being the lead in a drama. Timini Egbuson (Breaded Life) simply seems like he is in a different project entirely, like a parody film or an end-of-the-year school play. Bimbo Akintola (Ijakumo), bless her soul, plays her character so one-note and without much complexity that it hurts to watch. And yet, I cannot blame the actors entirely. The screenplay is bad– the drama isn’t compelling, the conflict is uninteresting, and the themes are paper-thin and ridiculous. The scenes are either underlit or lensed with high-key lighting, like a 90’s sitcom. The directing pulls a disappearing act.

By the end, the film never challenges the notion of Jennifer wanting to ‘give Ron a child’. She has some internal conflict when she joins the feminists, however, in the final story beat, she comes to her senses and returns to her husband, shunning the advice of her friends (who are nothing but deceitfully wicked), and her mother (who is merely bitter about one man and unfairly transferring that aggression). The Modern Woman is supposedly based on a true story, but that just further confuses me. At any rate, it must take some serious skill to make real life seem this boring.

The Modern Woman premiered in cinemas on August 18.

Join the conversation in the comments section or on Twitter.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

Side Musings

- I am tired of unnecessary drone shots. The key word here is ‘unnecessary.’

- There is one moment of visual brilliance here. It comes when Ron and Jennifer are arguing in their bedroom. The shot is composed using a mirror to frame Jennifer’s reflection and the mise-en-scène highlights their emotional divide. Kudos!

- Poor sound mixing. A phone rings and it sounds louder than the dialogue of the characters. There’s a tiny chance it was the theatre I saw it in that had the problem, but I doubt it.

- Someone needs to write an essay on the overabundance of poorly researched therapy sessions used as a plot device in many a Nollywood film. The key phrase here is ‘poorly researched.’

- So, in a film titled, The Modern Woman, all the women are either jealous, bad-belle types (Jennifer’s friends), unfairly cold (her mother), a temptress (Lucy), another temptress (Juliet Ibrahim’s character), or selfish (Jennifer).

- There is definitely a story to be told about how traumatic experiences color our perception of the gender of the perpetrator going forward, and about how modern men and women, because of social media, sometimes get delusional with our demands in relationships (e.g. seeing celebrities vacationing in Europe and feeling bad that your spouse cannot give you that, or something), but this isn’t that story. Not by a long shot.

2 Comments