If you’re a young up-and-coming filmmaker in the country right now, you probably want to be Jade Osiberu ‘when you grow up.’ In less than a decade, Osiberu has become a force to reckon within the Nollywood film landscape. She started out writing and directing a web series for NdaniTV, Gidi Up, starring OC Ukeje, Deyemi Okanlanwon, Somkele Iyamah, and Titilope Sonuga. Gidi Up was set in Lagos and followed the life and times of four young adults trying to make their way in the big city. It was produced by Osiberu and Kemi “Lala” Akindoju. The duo would work again, nearly ten years after, as producers on Gangs of Lagos. Osiberu’s other producer credits include Ayinla (2021), Sugar Rush (2020), and Brotherhood (2022).

In Defense of ‘Gangs of Lagos’ and The Future of Our Films

In Defense of ‘Gangs of Lagos’ and The Future of Our Films

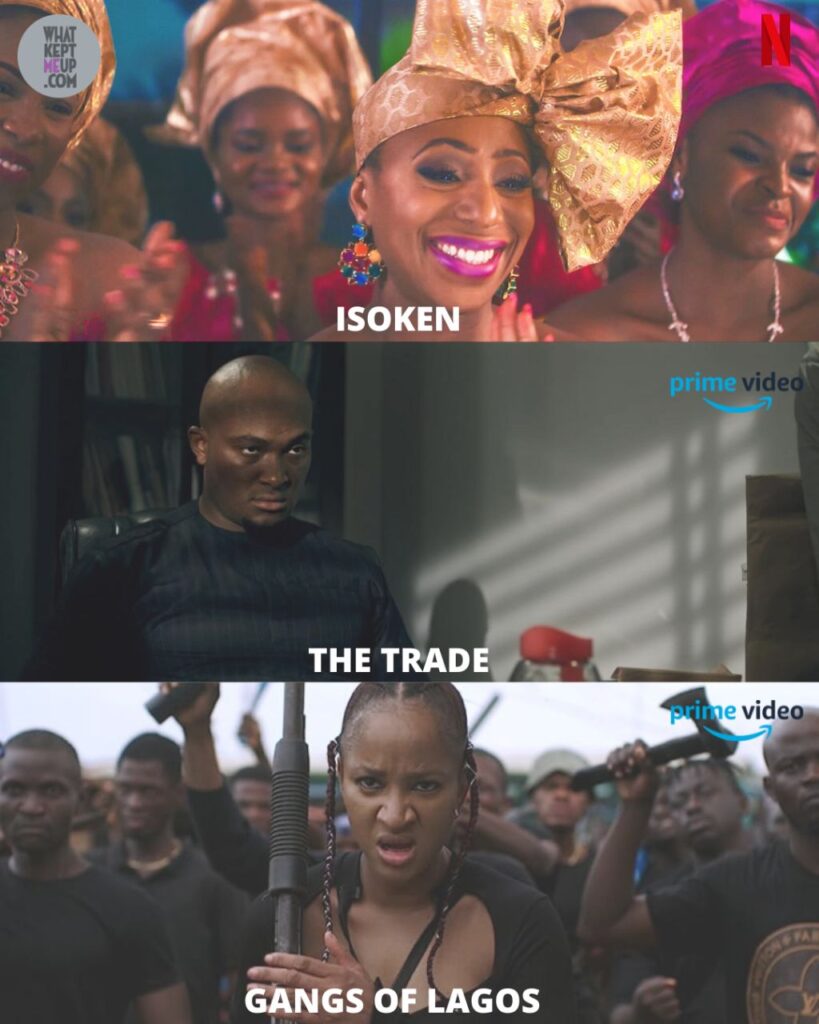

With Gangs of Lagos, released earlier this year on Prime Video, she has three writing-directing credits under her belt, and was catapulted into the stratosphere. In this article, I take a look at these three films, spotlight their high and low points, and what we can expect from Osiberu going forward.

3. Gangs of Lagos

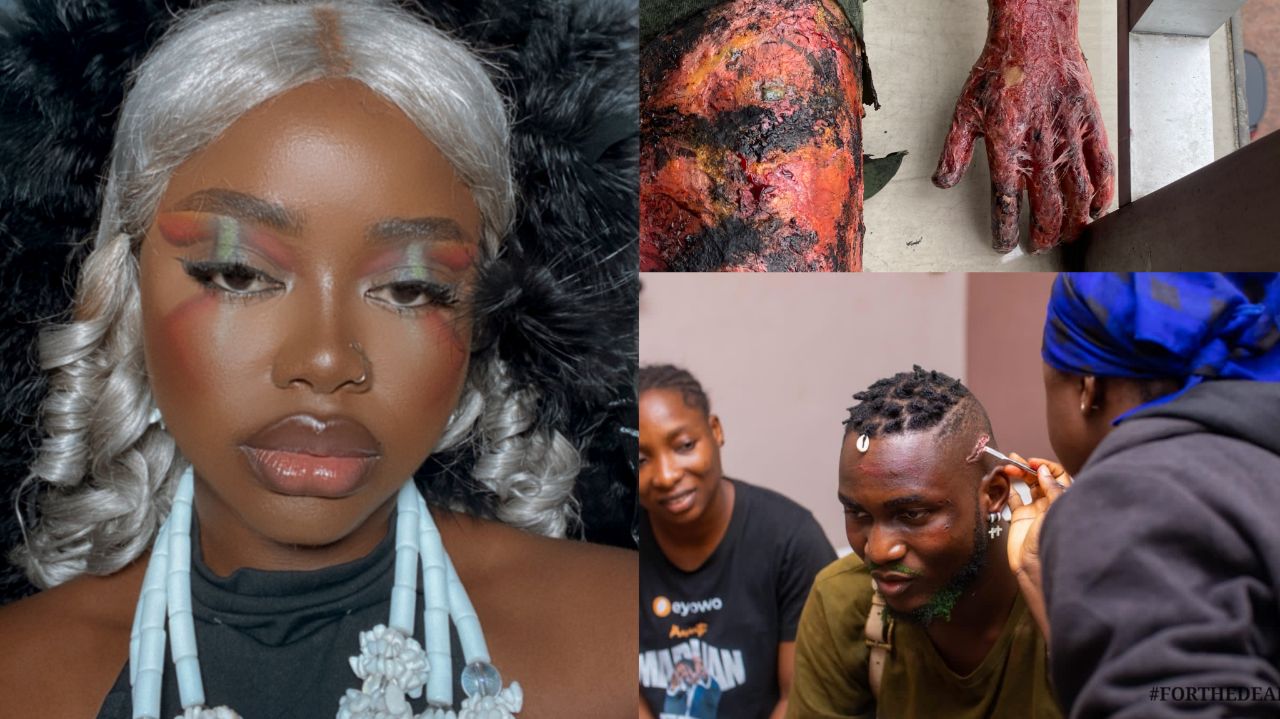

Gangs of Lagos is easily Jade Osiberu’s most ambitious film. In it, one observes flashes of City of God (2002), especially in Obalola’s voiceover narration, an element used to near perfection in City of God. The attempt to bring the setting of Isale Eko to life in every scene recalls a similar story decision by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, who turn the favelas of Rio into probably the most important character in the film, the titular City of God, devoid of any traces of Divinity and Providence.

There’s a hint of Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) as well, not only in its foregrounding of organized crime, but also in the way it features multiple characters and is presented in the style of an open world movie.

However, unlike its influences, Gangs of Lagos is a film that lacks direction. There’s been a recent trend in New Nollywood to churn out films which cast a spotlight on the dark underbelly of crime in Lagos, and the bloody nature of its politics. These films are typically brash in their delivery (for some reason, unsubtle is the name of the game) with garish neon lighting (which, more often than not, suits the grimy setting like a glove), bloodshed and violence in spades, and enough chest-thumping from hubristic characters to make a family of gorillas jealous. Whether it’s Far From Home (2022), King of Boys: The Return of the King (2021), Bling Lagosians (2019), Shanty Town (2023), or Collision Course (2022), the deal is the same: present the dichotomy of Lagos to the audience, a land of extremes, where the movers and shakers, well, move and shake, and ultimately shape the destinies of the common man, all the while motivated by greed, and ruthless in their reign.

The thematic underpinning of these stories is expressed in one moment by a character in Collision Course: “Sometimes, I think the Third Mainland Bridge is more than just a link between the Mainland and the Island. I think it’s a submerged metaphor for social stratification. On one side you have a Mecca for the bourgeois. For those on the other side, the symbol of success and an aspiration.” Then she goes on to mention the “hopeless and poor members of society that dwell in the slums underneath the bridge. I think these are the three sides of the Third Mainland Bridge.” This couldn’t be more true; there are two Lagoses, or three, or five, or fifteen, depending on the criteria of your socioeconomic classification. The issue is that these Lagos noir films seem to focus on this theme to the detriment of other parts of the story. Sometimes, a film demands to be loud and unsubtle, a narrative sledgehammer, if you will; sometimes, it’s best delivered with great precision and care, like a surgeon performing a septal myectomy on a pregnant woman in her third trimester. Most of the time, it’s a blend of both.

Gangs of Lagos is a perfect example of a film that doesn’t know how, or indeed, when, to exercise restraint. Because themes take preeminence, the characterization suffers, and so does the plot. The visuals are flashy. Some of the performances are compelling (Chioma Akpotha and a few scenes with Tobi Bakre come to mind), but the story is scattered. The film can’t seem to decide whether it wants to be about revenge and the cycle of violence, or the invisible hand of fate, or the disappearing futures of the eruku used by the street kings and politicians to do their bidding, or a doomed romance, or an action thriller a là John Wick, complete with unbridled displays of violence and gun-fu to boot (props to the stunt department though, who don’t get their flowers enough in film industries across the globe). As a result, it ultimately doesn’t quite come together, whether as social commentary or entertainment.

By the conclusion, I was at a loss as to what the film wanted me to feel. Is this a tragedy? What happened to Akande’s mother? Tenilola? How does he feel about potentially burning those bridges for good? The film doesn’t inform us, or even hint at an answer. Even with a voiceover narration that carries throughout the runtime, we aren’t privy to much of the interiority of our main character. I found myself trying hard to be pulled into the orbit of his motivations. When we meet him as an adult, he is supposedly saving up to move to San Francisco, but this only comes up once. When he decides to avenge Ify, and then, subsequently, take down Kazeem, the audience does not feel the weight of the loss of his goal to get out of Isale Eko, because he doesn’t either feel it or show it, taking it all in stride as having been predestined. Does(n’t) he fear that he might meet the same fate as both of his fathers? How does he feel that he isn’t living the life Nino wanted for him? That he couldn’t become university-educated like Teni?

This isn’t The Godfather, after all. This isn’t a tragedy where Michael Corleone becomes exactly what he despised in the end, creating a flurry of conflicting emotions in the audience. This is Gangs of Lagos, ambitious (and a commendable giant stride if I do say so myself) to a fault.

Sometimes, even with fewer cooks, too many ingredients spoil the broth.

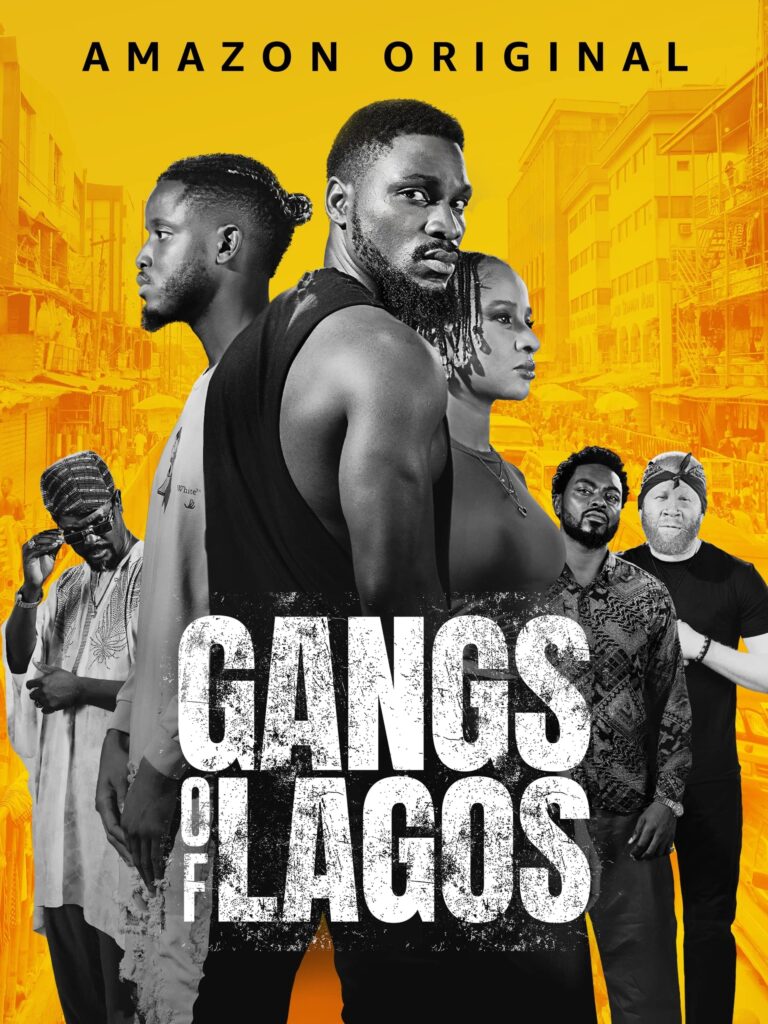

2. The Trade

I saw The Trade back in February, during the liquid cash scarcity. The theater was filled almost halfway, with people presumably excited to see the latest Jade Osiberu outing. There was some chatter at the beginning, as is the case in most cinema showings; however, halfway through the runtime, I noticed an odd calm. The entire place was quiet, save for the noise of the surround sound system. Every single person had their eyes glued to the screen, phones long tucked away; the film had us spellbound, and it was a beautiful sight to behold.

I walked home after the screening, an almost 40-minute journey, and the film was on my mind the entire time. I couldn’t stop thinking about how well paced it was. I went on my WhatsApp status and described the editing as crisp (a qualifier I still stand by) and the performances as grounded. It was my first cinema visit of the year, and I was excited and grateful it had been a great experience.

The Trade feels more put-together than Gangs of Lagos. There seems to be more care taken with its characterization, plot, and even cinematography. Its social commentary on the scourge of kidnapping in the country does not take away from its value as entertainment. If anything, they both feed back into each other.

The Films of Jordan Peele—Ranked

The Films of Jordan Peele—Ranked

Eric (Blossom Chukwujekwu) aka “the Chairman” is the leader of a gang of kidnappers who are as dangerous as they are discreet. Eric doesn’t even permit people to take pictures of him. He seems like a regular Nigerian: a family man, who attends church from time to time, focused on taking care of his children. That last point seems to form the basis of his motivation; he believes that any man who cannot take care of his family has committed the gravest of sins and, as such, scorns anyone who falls into this category. This is such a huge deal for him that it drives a rift between him and his father.

Watching Eric, I was reminded of another morally bankrupt lead character of a Nollywood noir film. None other than King of Boys‘ (2018) Eniola Salami. There’s something about watching hubris unfold on screen that is so captivating. Like not being able to turn your eyes away from a trainwreck. It is doubtless that despite his precautions, Eric will meet his end. Doubtless that his fall will be mighty and great indeed. The road to that destination, however, proves winding and perilous. Jade’s screenplay presents the audience with a juicy cat-and-mouse chase, with him slipping past law enforcement so many times it seems impossible. We’re rewarded at the climax though, when the officers have Eric at the end of a string, and catch him at the last minute. Even here, Chukwujekwu’s performance rings true. I’ll never forget the look on Eric’s face when he is eventually caught trying to flee the country: it’s the look of a man who once considered himself unbeatable and untouchable by the world, desperately looking for a place to hide. A self-proclaimed “big man” who in that moment would have done anything to be small.

A friend pointed out to me how Eric, and indeed, other Igbo characters in the film, feel like caricatures because of their heavy accents. One suspects the accents were meant to lend the world of the story extra credibility, but they don’t always work (especially coming from Nengi Adoki). Fortunately, this doesn’t ruin the film overall. Ultimately, its portrayal of the life and times of the characters, the kidnappers, and their methods of operation feels genuine. Combined with a powerhouse performance from Blossom Chukwujekwu, the entire experience of The Trade becomes even more compelling.

And isn’t that what good filmmaking is? I mean, a good deal of the craft is all about learning how to deftly construct an artifice anyway. But can you make the audience not only believe the events while they’re happening, but remain compelled by them long after the screen goes blank and persistence of vision ends, eliminating the moving images from their sensory memory? That’s the million-dollar question. With The Trade, Osiberu’s answer is a simple but resounding ‘yes’.

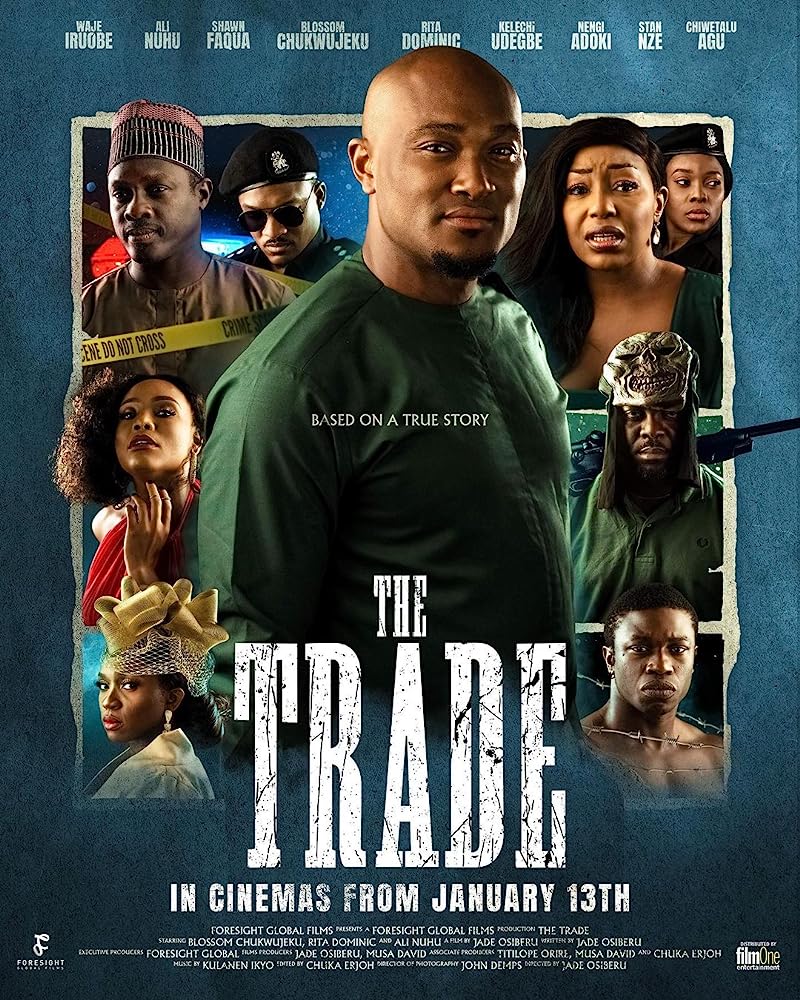

1. Isoken

I’ve discovered that for a lot of young filmmakers (those who have made three feature films or less), escaping the shadow of their directorial debut can be a little difficult, particularly if they burst onto the scene with a project that was on the lips of virtually everyone in the filmmaking/film watching world. Jordan Peele‘s Nope was one of my favorite films of 2022. Its success is a testament to how far he’s come since 2017. However, if you asked me to pick his best film, I’d pick Get Out (2017), without much contemplation. The same goes for Ari Aster and Hereditary (2018), Robert Eggers and The VVitch (2015), Greta Gerwig and her solo directorial debut Lady Bird (2017), and Julia Ducournau and Raw (2016). Jade Osiberu falls into this camp. There is no doubt that fantastic things lie ahead for her, but I don’t think her writing and directing (both in crafting the aesthetic of the film and the performances she is able to get out her actors) have been more in sync, more assured and right-footed, than in Isoken.

Watching it again for this retrospective, I was impressed with how simple the story is, and how well the execution works to elevate it. The premise is as old as time, but Osiberu layers the world of the story with enough details to make it stand out. Even fleeting moments, such as Isoken’s mother being obsessed with breaking curses with her anointing oil, apart from being an authentic Nigerian portrayal, are delivered in just the right amount and at the right moments too. The camaraderie between the four characters in Isoken’s friend group seems to fly off the screen, with every one of them facing their own minor conflicts and resolutions during the course of the story.

The standout performance is easily Tina Mba’s as Isoken’s mother, who is clearly enjoying herself as she swerves between acting as the antagonist and the comic relief rolled into one. Dakore’s turn as Isoken is a close second. The character is likable from the moment we set eyes on her. Her flaws are not too grating, her optimism not too saccharine; we are always on her side, a feat not too many romantic comedies or dramas can boast of. Seriously, just take a look at how many movies portray things like stalking, negging, lying and outright manipulation as romantic.

The film is also aptly self-aware, not to the point of incessant hand-wringing (thank God.) Like Isoken’s friends, viewers coming to the story likely all have their ideas about a relationship between a Nigerian woman and a British man, and Isoken, the film, respects them while telling its own version of the union. Someone else could take the exact situation and make a horror flick from it, or even action. Jade Osiberu chooses to tell a simple romantic story, Russian-dolled in another about self-confidence, and yet another about societal pressures and expectations. It’s brilliant. It’s unassumingly brilliant.

The Wedding Party (2016) has a better dance party ending though.

Essentially, Osiberu has had a blast of a career, and fingers are crossed to see what more she has in store. The Osiberu-owned Greoh Studios, back in 2022, signed a three-year deal with Prime Video to create and develop original feature films and scripted TV series. After the positive audience reception to Gangs of Lagos, the director mentioned in a tweet that there are murder mysteries, melodramas, horrors, crime thrillers, and even supernatural thrillers on the way. We look forward to the fruits of her deal with Prime Video.

Join the conversation in the comments section or on Twitter.

Sign Up: Keep track of upcoming films and TV shows on your Google calendar.

2 Comments